A conversation with Ralph Anspach, the man behind Anti-Monopoly

Monopoly, with its little red houses and pink five dollar bills and old-timey caricatures of J. P. Morgan, is a standard at family nights around America. But there’s something weird about Monopoly’s popularity. For one thing, it is a game that lionizes unregulated and potentially ruinous corporate business practices at a time when animosity towards bankers and cigar-smoking CEOs is through the roof. Also, it isn’t very fun.

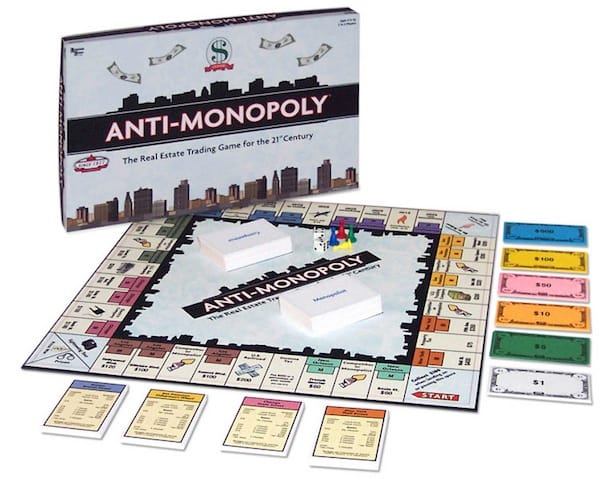

In 1972, Ralph Anspach, then a professor of economics at San Francisco State University, wanted to change that. With the help of a mathematician from down the hall, he created Anti-Monopoly, a smarter, fairer version of the Depression era game. Not unexpectedly, Anspach was sued for copyright infringement by the big guys. But as luck would have it, he and his attorney stumbled on the ironic truth about Monopoly’s anti-monopolistic roots. After nine long years of legal stalemate, Ralph won the right to produce his game. We called him last week to talk about the incredible case.

So how did Anti-Monopoly get its start?

I had played Monopoly with my family, and, the next morning, I had a terrible time returning from the university because of the oil crisis. When I got home, I started cussing out the oil monopolists. My eight-year-old son, who had won the game the night before, got very upset, and told me, “Dad, you’re a poor sport.” He thought I was talking about the game. At that point, it hit me. I decided to put out another game that would teach people what’s wrong with monopolies.

How is Anti-Monopoly different than the game everybody plays, Monopoly?

It plays very much like Monopoly. The big difference is that my game has a secondary battle going on between monopolists and small businessmen. It’s a strategy game where I introduced basic Econ 101. The monopolists behave like monopolists. They monopolize the colored groupings, raise the rent, rip-off consumers, and make a lot of money. The small businessmen can start building and developing immediately, but because they face competition, they are never able to charge the rates that the monopolists do. Both monopolists and competitors have the same chance of winning, which is not the way it is in the real world.

So you made the game and put it out. What happened next?

We had a huge success. In those days, just as now, people were really pissed off at monopolies. In the first year, we had orders for about a million games, and we had sold about two hundred thousand. And then the monopolists struck. Monopoly decided to sue me for trademark infringement, which began a nine-year battle in which Anti-Monopoly defended itself against Monopoly.

What was your argument in the case, and what was the other side’s?

We were fighting General Mills, one of the biggest corporations in the U.S., which at that point had bought Parker Bros. In order to show their trademark was infringed on, they had to show that people would be confused between Monopoly and Anti-Monopoly, which is obviously absurd, because people know the difference between something and its opposite. But as the case developed, the district judge made a huge legal error, and he opened up a different argument for us. That argument was the trademark on Monopoly was invalid. At that point, the hunter became the hunted.

You’re referring to the secret history of Monopoly, which existed as a common game before the commercial game we have now. What did you discover when you started digging around?

The story of the invention of Monopoly, as told by Parker Bros., was a great American opportunity story. During the Great Depression, an unemployed man, Darrow, went into a cellar and came up with Monopoly, and ended up becoming a millionaire. This turned out to be totally false. I began one year’s worth of detective work and uncovered all kind of weird things. The original game was an anti-monopoly game, played by left-wingers in a bohemian town. Then, for about 20 years, monopoly, with a lower case m., was played as a folk game on the eastern seaboard. It ended up in Atlantic City where a bunch of Quakers turned it exactly into the game we know. One of them introduced Darrow to the game. Parker Brothers, which was close to bankruptcy, got ahold of it, and the game began to take off. But it ran into the horrors of competition, because the same folk game was starting to be produced by others selling it at half the price. So, Parker Brothers got a patent.

So you were losing your legal battle up until you came across this information.

I ran into a district judge who was notorious for being pro-big business. He ruled against me twice. Actually, I had forty thousand Anti-Monopoly board games buried in a garbage heap in Minnesota. But I kept on fighting. I had a wonderful lawyer, Carl Person, who didn’t charge me anything. I have to be honest. If I hadn’t found him, I would’ve been destroyed, because the big guys use every trick in the trade to make it impossible for a little guy to win. We overturned the judge twice in the appellate. General Mills agreed that they would not interfere with the marketing of my game.

How has Anti-Monopoly done financially since then?

I’ve sold half a million Anti-Monopoly games in Europe, and only 10% of that in the U.S. We’ve been kept out of the mass markets. We know why, but I don’t want to go into that.

What kind of statement do you think Anti-Monopoly makes about the economy?

People on the left always think it’s a game against greed, and that it shows the better side of human nature. But that’s not what it is. I’m on the left myself, but I’m a pro-capitalist economist, provided the economy is not controlled by monopolies. In my game, the message is competition in a truly free market economy is a good thing, and is driven by people’s desire to make money. A monopoly is the flipside of a market economy. It’s not regulated by government, but controlled by a few people at a fixed price. In Anti-Monopoly, the monopolists are the bad guys. My game doesn’t give the subliminal message, which Monopoly does, that monopolists are great. Monopoly really gives the wrong idea about the way a well-functioning capitalist economy should work.