For more in-depth game writing, back our Kickstarter!

Here comes the trashman! He’s strutting down the highway in his scrap metal suit, tin cans rattling up and down its legs, soda bottles and glue dispensers falling out the cracks between its plates, cereal boxes bobbling on the tips of his metal fingers. He’s blasting “The Wanderer” with no headphones on and waking the mole rats up. He’s bounding downtown like he owns the world. He intends to put all of it into his pockets.

He works fastest indoors: his vision jumps from floor to desk to shelf, hunting for the red ink of a vintage magazine cover or the yellow and blue markings of a bobblehead, which will sometimes alight next to a terminal like a rare warbler. Rarely finds them. He consoles himself by sweeping whole tables of junk into his trousers like a cartoon bank robber, loading up on TV trays and microscopes and circuit boards.

He carries almost three hundred and fifty-two pounds of garbage. He needs to stay high as a kite and blotto just to keep moving. When he gets hooked he turns to the miracle drug Addictol to straighten himself out. (Where does he stick the needle? Unknown: you hear only a pneumatic pssh!) You can’t get addicted to Addictol, but if you’re addicted to picking up trash it’s pretty much the same thing.

The sign of his passage is a bloody mess, a trail of pulped heads and innards

You couldn’t lock him up for acting like this—you’d have to lock up everybody. There’s a bit of trash-mania in all of his fellow Bostonians, who each keep a grab bag of drugs, 210-year-old processed food, and eccentric mementos on their person. Every raider seems to be on his way to a championship game of What Have I Got In My Pocket against Bilbo Baggins: this one has two guns and a baby rattle, that one a pool cue and a spatula. Mush-faced ghouls with radiation-pattern baldness carry hairbrushes. Even a regular Diamond City citizen like Earl Sterling keeps a human spinal column in his filing cabinet for no reason at all. The more powerful someone is, the more garbage they carry; that’s how the trashman knows he’s the baddest dude of all.

He is, you come to realize, not cleaning up but actually spreading trash. The sign of his passage is a bloody mess, a trail of pulped heads and innards scattered like fat red berries. And to this refuse he casually adds junk that has lost its appeal, hot plates and old shirts and pipe pistols, to make room for finer trash picked out from the gore. He can’t bear to leave the good stuff behind.

This last fact often brings on the great crisis of our hero’s life. When he runs out of booze and pills, he can barely crawl his way back to Bunker Hill. The weight of his collection roots him to the ground. This bouncing figure of fun, the trashman, now staggers into the market on gouty legs. Residents turn to watch the slow progress of the famous glutton, swollen and sick with the trash that he loves. (Their expressions remain frozen and impassive.) When at last he finds a merchant’s table or workbench to lean over, he releases a great torrent of all the junk that Boston could not digest: toasters and beakers, old gum and raw meat, moldy bills, rusty guns speared with nails, cartons of ancient cigarettes.

And as soon as he heaves out the last screw, the weight is lifted; the twinkle in his eye returns; the music starts up again; and he spins on his heel to return to the waiting world of trash.

///

One of the most ubiquitous items in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion was a set of calipers. They were stuffed into unlockable containers, houses, and trolls’ bodies. Players couldn’t do anything with them. Merchants didn’t want them. They were “clutter items” that took up space and punished players who used the “Take All” button. The designers’ enthusiasm for them was mysterious.

In 2010, future Fallout 4 lead designer Todd Howard revealed to Official Xbox Magazine that the team had originally intended to add a quest that would tie the whole caliper thing together. “One of the guys pitched that you pick up calipers and take them to a swordsmith who makes you a sword called Excaliper,” Howard said, but this payoff was cut from the final game.

I’m not sure if this story was true or if it was Todd Howard true, but it suggests that even in 2006 there was a Patient Zero within Bethesda, someone carrying the idea that would infect and define Fallout 4: what if players had a reason to pick up every useless piece of junk in our game?

///

Fallout 4—or, as series fans will remember it, “the one with all the trash”—begins pre-apocalypse, in the shockingly clean Boston suburb of Sanctuary Hills. There’s a live-action cutscene about World War II, nukes, and war never changing that has almost no relevance to the story that follows. It actually seems like war has changed a lot since WWII, which was not about a junkie killing thousands of other people in order to take their glue.

what if players had a reason to pick up every useless piece of junk in our game?

We meet a wife and husband and their odd-looking child, and you can take the time to deform their faces as they peer into the bathroom mirror (sadly, the parents will not hold their baby up to the mirror and let you reshape him into Waluigi, or whoever). That’s about the only thing you have time to do in 2077 before air raid sirens go off and you’re pushed into a vault. Fallout 4 won’t delay the action long enough to give us a taste of the mundane, as games like Lost Planet 3 did—we don’t go to the block’s Halloween party or argue with a neighbor about the tree on the property line—and never sets up any of the sentiments about this period that the protagonist later expresses in dialogue. There is no emotional dimension to the old neighborhood, the old world; there’s no reason to miss it after our character is transported to the megafucked trashscape of the future. Suburbia doesn’t feel half as real here as Stanislaus Braun’s Twilight Zone simulation of it did in Fallout 3.

It’s no wonder Fallout 4 rushes toward the violence of the wasteland. The guns of the future include some real rock-and-rollers, and the search for new gun-scraps is irresistible. But the game’s approach to dialogue is a disaster. Never known for their polished scripts, Bethesda’s writers are now hobbled by a rigid four-option format in which each choice is expressed in three or four words at most. The menu is often as simple as “YES,” “NO,” “MAYBE,” or “[NOUN]?” In complex situations, the prompt may be as brief as “COMPROMISE,” leaving you to wonder which of a dozen conceivable solutions the protagonist will suggest. The thickets of dialogue in Obsidian’s Fallout: New Vegas, the quest branches that let you play both sides against the middle, the growth of old obligations around the player—it’s all been slashed and burned. In conversation, Fallout 4 is as simple as they come.

Before release, the internet was already jeering at a scene in which the protagonist is asked his opinion of “the news” and can reply “HATE NEWSPAPERS” or “SUPPORT NEWS.” The whole game talks like this. Late-period Bioware is the obvious model, but even those games dignify players with complete (short) sentences, and they occasionally splurge on two clauses. Here it feels like we’re stuck inside one of those low-intelligence playthroughs of Fallout 2.

The storytelling in Fallout 4 looks especially clumsy next to the work in Witcher 3, and I have serious questions for anyone who puts the former above the latter. Do you notice how in Fallout, people often carry on conversations without moving their lips, talk to you with their backs turned, talk to someone else while staring only at you, or speak while repeatedly waking up and falling asleep again—while those in The Witcher largely respect the conventions of human speech? Do you notice how almost every conversation in Fallout is filmed with the same static over-the-shoulder shots, sometimes cutting to the same awkward two-shot that isn’t framed correctly if the protagonist wears Power Armor—whereas those in The Witcher are full of tracking shots, long shots, and choreographed motion? Do you remember how The Witcher could get a laugh just from a character’s expression or gesture—whereas Fallout makes you wince at the stiffest animations in a major release this year?

But the real issue with Fallout 4’s dialogue isn’t the presentation but the response. In the original Fallout, mouthing off to NPCs could derail quests, start fights, and quickly send you to a mordant game over screen. You could talk your way into a raider stronghold and then decide to hit on the chieftain’s girlfriend, but the punchline wasn’t really what you said: it was the entire room of wired-up Khans attacking you. Fallout 4, by contrast, is barely listening. Most quests continue down the same path no matter how rude you are.

The pattern is set in the game’s prologue, when a Vault-Tec salesman asks for your signature and you can reply “NOT INTERESTED” then “NOT RIGHT NOW” then “GO AWAY” then “NO” then “I SAID NO.” Then your spouse walks up and signs it anyway. A surprising number of questgivers in Fallout 4 are salesmen at heart: they hear “no” as “tell me more.” It doesn’t matter how hard you try to burn your bridges with guys like Preston Garvey or Edward Deegan. They are unflappable.

You can dress up as whoever you want in Fallout 4, but you can only role-play as the trashman.

Speech checks (which now rely on the Charisma stat, and are easily gamed) rarely touch the narrative. They’re used more as a revenue stream than for emotional payoffs—like lockpicking or hacking, they funnel extra money and experience to the player. You coax more caps out of your employers by selecting MONEY then MORE MONEY then EVEN MORE MONEY. I was overjoyed the first time I found a speech option that wasn’t MONEY or FLIRT, but there are very few of them that actually save you time or open up a desirable quest branch. (It’s worst at the end of the game, when your options dwindle to “blow up these guys or blow up those guys,” and the “explain why this plan makes no sense” speech that should be there is not.) A second playthrough suffers, especially in comparison to New Vegas: here you talk to the same people, clean out the same factories for the same reasons, and pick up the same aluminum canisters on the way.

The lines that used to be checked against a Speech skill or stats like Perception, Intelligence, and Strength have been removed from Fallout 4, taking with them the moments that used to distinguish one RPG character from another. You can dress up as whoever you want in Fallout 4, but you can only role-play as the trashman.

///

But Fallout 4 does one thing so well that you can mostly forgive, if not ignore, its awkward treatment of the player character.

Bethesda’s team creates maps that are a joy to explore. They crash wooden ships into the tops of buildings, turn Walden Pond into a drug den, build a Chopping Mall-style galleria staffed by malfunctioning robots. It’s very hard to walk in a straight line through their world—you zig-zag between all the things you can’t resist checking out.

It’s the same thing Skyrim was sold on, of course. But the Commonwealth is better at keeping its promises, I think, than the province of infinite quests. It’s full of unmarked trails, sets of holotapes like the “Ladies Auxiliary” notes you find around Cambridge, and little handcrafted spaces like the Boylston Club, the site of a very exclusive group suicide. Even when charging through rooms on the hunt for fresh junk, these scenes bring you to a halt. The sheer number of stories embedded in locations feels like a conscious correction to Skyrim, which repeated itself to the point of discouraging explorers.

Bethesda’s team creates maps that are a joy to explore.

The game’s larger sidequests try their hand at every genre from H.P. Lovecraft homage (the Dunwich Borers pit, a nod to Point Lookout) to hard-boiled fetch quest (“Long Time Coming”), with mixed success. The kitchen sink approach is at its worst in “Confidence Man,” a Diamond City quest that follows a familiar sitcom plot without adding even a hint of Fallout personality. But it also leads to gems like “The Silver Shroud,” in which the player agrees to act out the increasingly bloody crime-fighting fantasies of a man who idolizes a pre-war, The Shadow-ish radio hero. I don’t think any other quest quite matches its absurd enthusiasm—“Last Voyage of the U.S.S. Constitution” comes close, but bad voice acting deflates it. Another good one, “Human Error,” hinges on a personality test that variously recalls Blade Runner, Ultima character creation, and (a wiki informs me) the test at the start of Fallout 3 that I always skip.

The game’s human characters are forgettable. But its honest robots, the goggling Mr. Handys and Gutsys and their fellow RobCo creations, are a pleasure to encounter. Stationed as bartenders, janitors, and tour guides, they’ve all decayed or prospered along with their surroundings. Some march out for charmingly stupid little demonstrations, like the Protectron Parade at Robotics Pioneer Park; others are permanent installations, like the bowler-clad bartender Whitechapel Charlie, who pays the protagonist’s fee while grumbling that it’s “a right kick in the Alberts.” There’s an addled machine that nearly murders you with a cup of coffee, and an armless Handy model that takes up a post as a ship’s bosun. Their voices—eternally peppy, deluded, marching happily toward disaster—are the game’s authentic comic spirit, one very different from the caustic tone of the original Fallout.

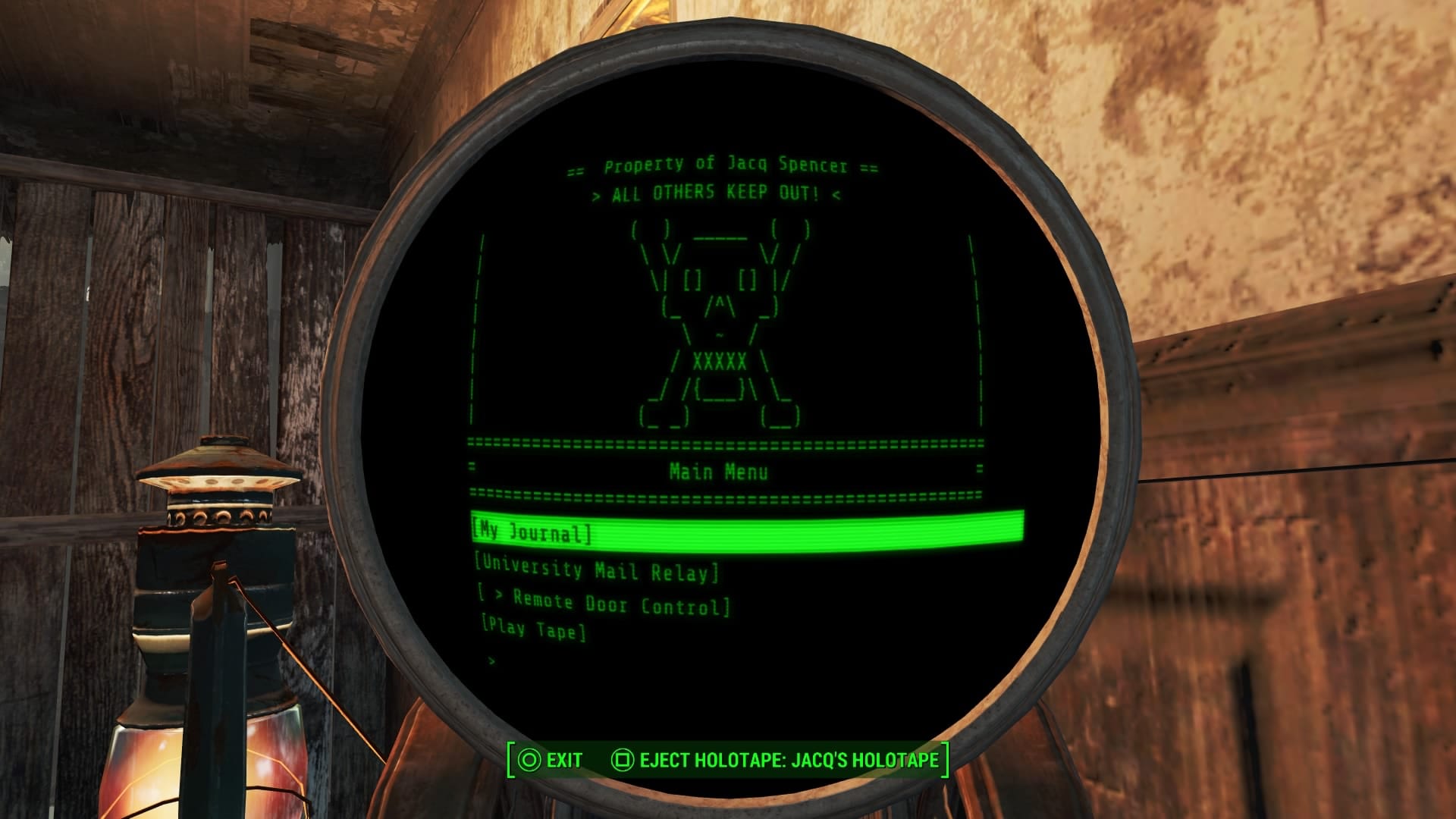

But even they are absent from the game’s best and loneliest story. You’ve got to head down to the desolate settlement of University Point to find it, and there’s no quest flag that I know of to lead you through. If not for a few patrolling enemies, this section of the game would be a full-on walking sim: you wander through the pre-war college halls and student union, which more recently hosted a small community, which even more recently disappeared. From notes and terminals linked to the old university mailing system, you piece together a grim and surprisingly layered narrative: what happened to a father and his daughter, what happened to a professor before the war, and even what happened to a research assistant. This is what, on a good day, you find buried beneath all the post-apocalyptic junk: an honest-to-god story, plainly told and brutally effective. You also find a nice gun.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.