Gone Home’s Steve Gaynor on how the internet ruined adventure games and reliving the 90s

As David Foster Wallace once elegantly put it, “Fiction’s about what it is to be a fucking human being.” And these days being a fucking human being involves a keen nostalgia for the pre-internet 90’s, having multiple perspectives on yourself and on everything around you, and pretending we understand semiotics.

By my count, that makes Gone Home a substantial work of fiction. But unlike most prose literature, the story is told through items. Yes, items. The things you come across, like shipping forms and postcards, post-it notes and nutrition labels, move the plot forward. We talked to the game’s narrative designer Steve Gaynor about environmental storytelling.

We just wanted to make a game about exploring and discovery.

KILL SCREEN: Gone Home strikes me as literary.

Steve Gaynor: Well, there are a lot of words in it!

As a writer, how do you get into the mindset of your characters?

I never do drafts on the computer. I go into the backyard or the living room and write in a notebook. There’s something about the pace of doing that, the evidence that’s left behind by writing something, scratching out, rewriting it, feeling out what direction the character’s voice needs to go in.

That seems to be a theme of the game. That there was something tangibly better about the way we communicated and even wrote things down pre-internet.

Not that the intention of the author is important, but there wasn’t any kind of qualitative nostalgia. We just wanted to make a game about exploring and discovery. We wanted to have a lot of little pieces of information scattered all over the house for you to reconstruct. If we set it in 2013, you’d find someone’s iPhone and read all the text messages. The whole story is in that one artifact.

The evidence that’s left behind by writing something, scratching out, rewriting it, feeling out what direction the character’s voice needs to go in.

Do you think that the internet has ruined the adventure game genre in that way?

It makes it harder because so much information is centralized. But I don’t think it’s impossible. Suspense movies have adapted. The suspense stories that were told well in 1998 may no longer be relevant in today’s setting, but there definitely are interesting stories going on.

At least you can say it’s changing what an adventure game is. In fifty years, when we all have robots and the whole house is controlled by a computer, we probably won’t even need keys.

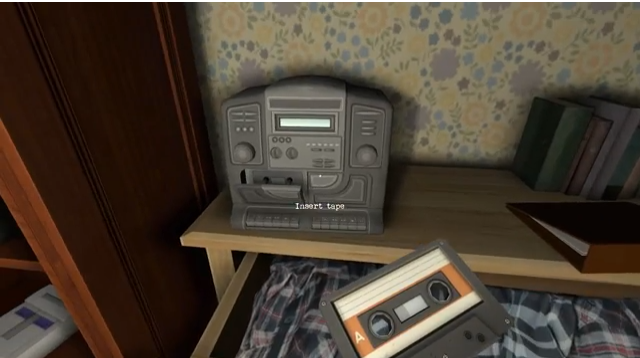

It’s definitely changing. It’s nice how much physicality there was in the nineties. You pick up a cassette tape and you put it in a tape deck. It has a very satisfying payoff that is different than finding an iPod and navigating through the user interface. But with Gone Home, it’s more about us being faithful to that era than a reaction to this one.

You’re projecting how these people feel. There’s no way of knowing it directly.

You’re telling a story based around a person’s belongings, instead of the people themselves, which strikes me as the complete opposite of how things happen in a novel, where you know the character’s thoughts, and how they feel about other people.

Novels excel at expressing the characters’ internal states. In Gone Home, we have Sam’s voice in the form of audio diaries. But it’s at arm’s length. We applied as light of touch as possible. You start by only seeing the evidence of these people, the impression they left behind. You don’t have direct access to the internal state. You’re projecting how these people feel. There’s no way of knowing it directly.

Is that something you struggled with–the balance of how much of this is the player’s story, versus how much of this is the character’s story?

We wanted to be hands off, because there is this dissonance between the player and the player’s character. If we tell you too much about Katie and who she is, it gets into this weird space where it’s like, “I’m playing as her, but I’m discovering stuff about her that she already knows.” So we made her this presence who you only get the most basic facts about. This way, it doesn’t have the baggage of, “I’m finding out my own story and that’s weird!”

Otherwise, it’s like amnesia.

Yeah exactly. The reason amnesia is so incredibly common is because you have to be discovering all these facts about the character and the character is finding them out too. I guess they have no memories.

Images via The Fullbright Company.

Additional editorial support by Nicholas Milanes