Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime takes Chris Ware to outer space, whether he wants to go or not

Outer space is black. Infinite. Empty. Even lonely.

It doesn’t have to be. Indie developer Asteroid Base has slapped color into the final frontier with Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime, painting its battleship bright pink, its backgrounds ocean blue, its aliens neon green. They’re like jellyfish in their tiny dome-shaped ships while bunnies with little hearts twinkling like stars above their heads dance under a rainbow on an orange planet.

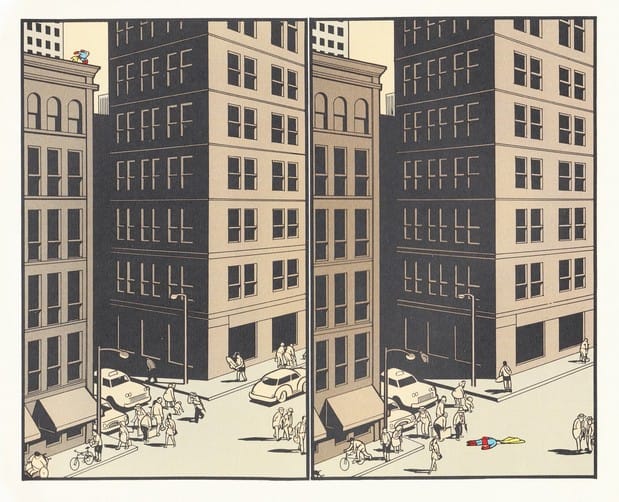

It’s modeled in part after the work of illustrator Chris Ware, but somehow, this space wonderland is the very opposite and the exact same as how he describes his own art.

“I wouldn’t consider my fictional comics writing/drawing as much of a style but more of a quasi-typographical approach that tries to be as transparent, clear, and uninteresting as possible,” Ware told me. “It’s designed to suit both the way in which we reduce the world in order to understand it and to ease the reading of comics versus their simply being looked at—as is the case with virtually every other example of Western visual art.”

The visual design of Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime is anything but uninteresting; it is a simplification of the universe, however. Creative director Matt Hammill and studio co-founder and illustrator Jamie Tucker told me they wanted their game to pop.

“At the beginning of the project, everything had a texture to it—it was a bit busy,” said Tucker. “We quickly realized that was already going to be too much visual info to take in, so we wanted to emphasize simple shapes and flat colors. Also, after we settled on the name of the game, it started to feed back into the look.”

Those shapes and colors help Lovers become more than the typical, realistic, Star Wars-esque sci-fi game we’ve seen time and again. But Asteroid Base intentionally avoided black, a color that would only “deaden the world,” Tucker says, instead of making it come alive.

Asteroid Base created and evolved its design by looking at a variety of sources: Chris Ware, Soviet-era match books and diagrammatic illustrations, Powerpuff Girls, Sailor Moon, Scott Benson, and Battletech.

The studio ended up with a sense of minimalism that it credits to Chris Ware’s influence—how all the small embellishments and inner workings add up to a bigger picture. That’s important in a game where survival depends on the successful distribution and completion of tasks on a space station, where working together takes both human teamwork and machine-like efficiency.

What you see at a glance is more than you need to.

“An interesting thing though is that when you watch the game it appears more complex than when you play it because in gameplay, most of your focus is on your own little field of action,” said Hammill. “You just have to trust that your partner can take care of their side of the ship.”

Those varied layers of function and design are evident in Ware’s work. What you see at a glance is more than you need to, but start taking the picture apart, and it all comes together.

“You look at something like his Building Stories, and there are these fiddly bits of books and ephemera, each one is a little snapshot of the larger narrative,” said Tucker. “The whole thing strewn across a table looks like a mess, but once you dive in to each part, you start to see how it all fits together.”

Lovers is like that, too. A lot happens onscreen, so much that it’s an information overload, Tucker says, but your attention is where it should be: on manning the turrets, dodging asteroids, whatever.

“That idea of balancing the small picture with the big picture was important both for game design and aesthetics,” said Hammill.

Ware explains it a different way: “I’ve been described as both ‘minimalist’ and impenetrably complicated, which is fine with me; the scale and texture at which human beings experience reality is a mingling of perception and conception, or put another way, on a blend of seeing and memory. I try to get at both of these things in my comics, as well as at something of the impossibly ever-more-tangled nature of experience, if saying that doesn’t make me sound too much like a stoned dorm supervisor.”

The developers showed me a simple drawing of a robot in a spaceship that Chris Ware had done that inspired them. That strip was “very loosely inspired by a 1920s ‘Buck Rogers’ sequence,” Ware told me.

What is his version of space like, I wondered.

“I find it very reassuring to think of how meaningless and infinitesimal our lives are.”

“I’ve done a few stories set in space, both imaginary and real, and I would figure that ‘space,’ as we think of it, would be black, huge, and soul-crushingly indifferent,” Ware said. “At least that’s how I see it on a clear night. I find it very reassuring to think of how meaningless and infinitesimal our lives are, and how overrated consciousness is. Which is one of the many reasons why first-person shooters are so disturbing to me.”

Everyone looks at the stars and sees something different. Where Ware sees something dark and empty, the developers of Asteroid Base have found vibrant new signs of life. Space is as vast as our imaginations. Anytime artists go there, they’re charting unexplored territory.

Lead Image via Reverend Aviator