Milan & Neilson Koerner-Safrata: The myth and poetry of game engines

They’re identical twin brothers, but be sure not to confuse Milan and Neilson Koerner-Safrata for a dynamic duo. Though the pair houses their game work under the studio SCRNPRNT, they are “more like two parallel game designers,” Neilson explains. Between the two, however, they’ve utilized the game engines they grew up with in innovative ways—refashioning Age of Empires into an anthropogenic critique, imagining Counter-Strike’s Dust II in a playerless future, and more.

We spoke with Milan and Neilson as they debated the role of games in society, championed the poetic elements of game engines and virtual worlds, and how they’ve learned to ‘unlearn’ all they’ve been taught about games.

Can we begin by talking about your upbringing and when you first knew that you wanted to be a creator or an artist?

Milan Koerner-Safrata: I was sucked into lush game worlds, like Machinarium by Amanita Studios. When it came to creating those game worlds myself, I realized that the gargantuan process of making an environment was less interesting than what happens inside it. I moved from a more visual fine arts perspective to think more about the logical ends and action space inside the game worlds. From then on, my engagement with games and reasons for making art inside them have been about re-investigating what was seductive about them when I was younger. I’m also thinking about creating games that are more reflective of mental space versus a physical environment.

Neilson Koerner-Safrata: There is a common theme where we have an unlearning of what we saw was so enchanting about games. When I was 10, I thought my entire life would be making video games. We’re from the second generation of game developers, but many myths about game development persist… Things like it’s a new medium, and you can make your mark, and there’s so much that hasn’t been explored that hasn’t been done.

We had to unlearn what was seductive and addictive about games when we were young. That’s why deconstruction is a tool that I commonly use when looking at games. There’s so much there, and we’re still trying to pick apart our early experiences to see what was exciting and interesting, instead of thinking of games as this new thing—for me at least, not for Milan.

Can you talk about the games from your childhood that marked your coming of age and how your work aims to deconstruct them?

Milan: One of the biggest turning points was Minecraft, which is hugely commercially successful. It had that feeling of limitless potential built into the game system, and I could experience that as I played it. I got everything I wanted from the sense of big promising virtual worlds and the low-fi nitty-gritty. Age of Empires played a huge role in my childhood. Maturing past that into some more personal relationships in the game world, versus, in that example, an incredibly exploitative reality.

Neilson: Our practice is about taking our digital and virtual experiences and trying to relate them back to our lived experience. Now, Microsoft is now trying to take Minecraft and pull it out of the computer to sell augmented reality products—whereas Milan wants to explore more of the interior experience.

All games are kicking and screaming as they get pulled into the real world. They’re being forced out of their little shell, like Minecraft being used for commercial means. I’m interested in how the games from my youth are aging with me. Age of Empires is still an ongoing intellectual property that Microsoft develops and will potentially spawn my entire life, from Age of Empires 1 to Age of Empires 20.

Milan, you attended art school before going on to NYU’s Game Center. Neilson, you went through the more industry-oriented interactive media program at USC. How have these distinct tracks shaped your concepts of creation?

Neilson: I’m part of the generation who said, “When I go to college, I want to get a game design degree because this is what I want to do.” I went through USC in their Interactive Media department. There are many great people there, but I was less sure about my desire to spend a lifetime making video games by the end of the program.

That’s the unlearning I’m still trying to do, because that didn’t quite satisfy me. I’m looking for the part of the world where game design work then meets some larger, broader structure instead of the interior bubble. It’s part of a larger movement to fit game engines and digital experiences within larger systems.

Milan: I spent a year at RISD before I transferred to Brown. When I was there, I began to feel like the center of any artistic practice I was in should understand the material. I was mostly doing abstract painting work, and I was enjoying the feeling of working with the media. It was drawing or painting; it was making marks… Small-scale stuff that would lead to larger impressions. At Brown, it was a mixture of things, but chiefly among those was Digital Language Arts, which is this interesting academic discipline that evolved out of hypertext writing.

Much of the work being done in that space, like concrete poetry and hypertext writing, looked at the different material dimensions rather than the language and the text. Also, the whole group of people inheriting tools from this big tech explosion. The same way that concrete poets were taking apart typewriters and whapping the keys on paper. Coming from that program, I was carrying this feeling of, What kind of small decisions can I make inside a game engine? What kind of materiality already exists there that can be operated on?

At NYU’s Game Design master’s program, I looked at doing these abstract smaller experiences, doing many prototypes there. The first big project that I did on a team was this Dada-influenced game that was mostly a collage piece where you’re stomping through these generated worlds, amassing items, and wading through a series of sprites. For me, that was throwing everything at the wall and seeing what would stick. Since then, I’ve been trying to pare down my ideas and look at games in their most abstract sense to see what kind of experiences I can recuperate.

SCRNPRNT AS A TESTING GROUND

What compelled you to start working as SCRNPRNT and say, “Okay, let’s start making things under this name?” I’m also curious about the name SCRNPRNT.

Milan: It’s a play on [the] print screen [key], which we now realize was, unfortunately, a trendy start-up technique of removing vowels from a name [laughs].

Neilson: It has to do with the analog-digital interplay of screen printing as a practice, and the digital means of copying.

Milan: The mechanical, repetitive nature of game development games and computers is what made us conceive of it as SCRNPRNT. It felt inevitable that we should come together and put our ideas under this umbrella. We were both unique in trying to come at games from different angles, even if we don’t necessarily agree.

Neilson: It’s a testing ground as we continue exploring things. Milan’s current project is Stellations, and I’ve been working under the vector of DUSTNET and The Garden of Earthly Delights, which are the deconstructions. I want to start moving away from the deconstructions and into the game engine explorations of simulation. I’m exploring real-time art and game engines as installations in an institutional context.

Milan: Adopting the studio format for the sake of presenting games as arts felt important. I’m looking to do more traditional art-making and collage and copperplate etching. Having that housed under that name is important for me to have a certain professionalism about it to begin fleshing out this constellation of ideas.

When working on projects, is there a conversation that’s happening; are you checking in with each other? I’m curious about the degree of collaboration when you’re working on something together.

Milan: It’s mostly arguing about the way that the thing should work. With DUSTNET, I was repeatedly angry that Nielson wasn’t trying to create this Tower-of-Babel style thing on the online server. I wanted it to be a grotesque labyrinthine server. He was more like, “No, I’m going to play it straight.”

Neilson: Arguably, we’re bad game designers. We’d rather dink around in game engines. Most of our conversations are hashing out more of, Does this do what you want conceptually? Even if it’s not fun or it sucks, is it pushing its rhetorical point successfully? These are usually most of the arguments that go on.

Milan: We disagree on what the effect [of projects] should be. I thought that DUSTNET, more than anything, should be this great artifact. The effect Nielson was looking for was more of a playground XR. So I was already thinking about it as a 3D world versus a set of tools and platforms.

Neilson: As you can tell, the collaboration’s very light. It’s mostly asking about opinion. Very rarely do we step into each other’s repositories and actually dink around with the code. That’s not to say it won’t happen.

It seems strangely ideal that you both have your own lines of thought and ways of making things, but that you still also have each other as sounding boards. I had a question about how the general creative process begins, but I’m sure it’s very different for both of you.

Neilson: This is actually a similarity between us. We both do start with a visual. Milan, would you agree with that?

Milan: I find it hard to work on a project until it looks okay. I absolutely hate game engine default settings.

EDENS AND ABSTRACTION

Garden of Earthly Delights reimagines Age of Empires into a Hieronymous Bosch triptych. How did this combination come about?

Neilson: It was a very rare collaboration between the two of us.

Milan: My visual was getting the animals all frolicking together in the engine. Then, more of the Eden-esque idea came around. That’s how our ideas developed, and our ideas around the pastoral fantasy games started leaking in. Then Bosch, because why the fuck not? It’s iterative. The big shift was once we realized we wanted it to be less about the frolicking and more about the humans in the space doing the hunting. Then adjusting that to be the triptych after it happens.

Neilson: Most games these days are image-making. Luckily, we come from a visual background in a sense. Visuals and image-making are the most rewarded part of the process. If you get a visual, the rest comes along.

Milan: There is a cynical viewpoint of games that they are like systems that have skinning applied to them. I don’t agree with that—whatever the skinning, the framing, and the lens you use will have a huge impact on how the player receives the game. Having that be correct for me is more important than getting networked multiplayer because every multiplayer game has that.

I noticed a monochrome, bare-bones aesthetic thread across some of your projects, and I’m curious to know if there’s a reason behind the stark black-and-white visuals.

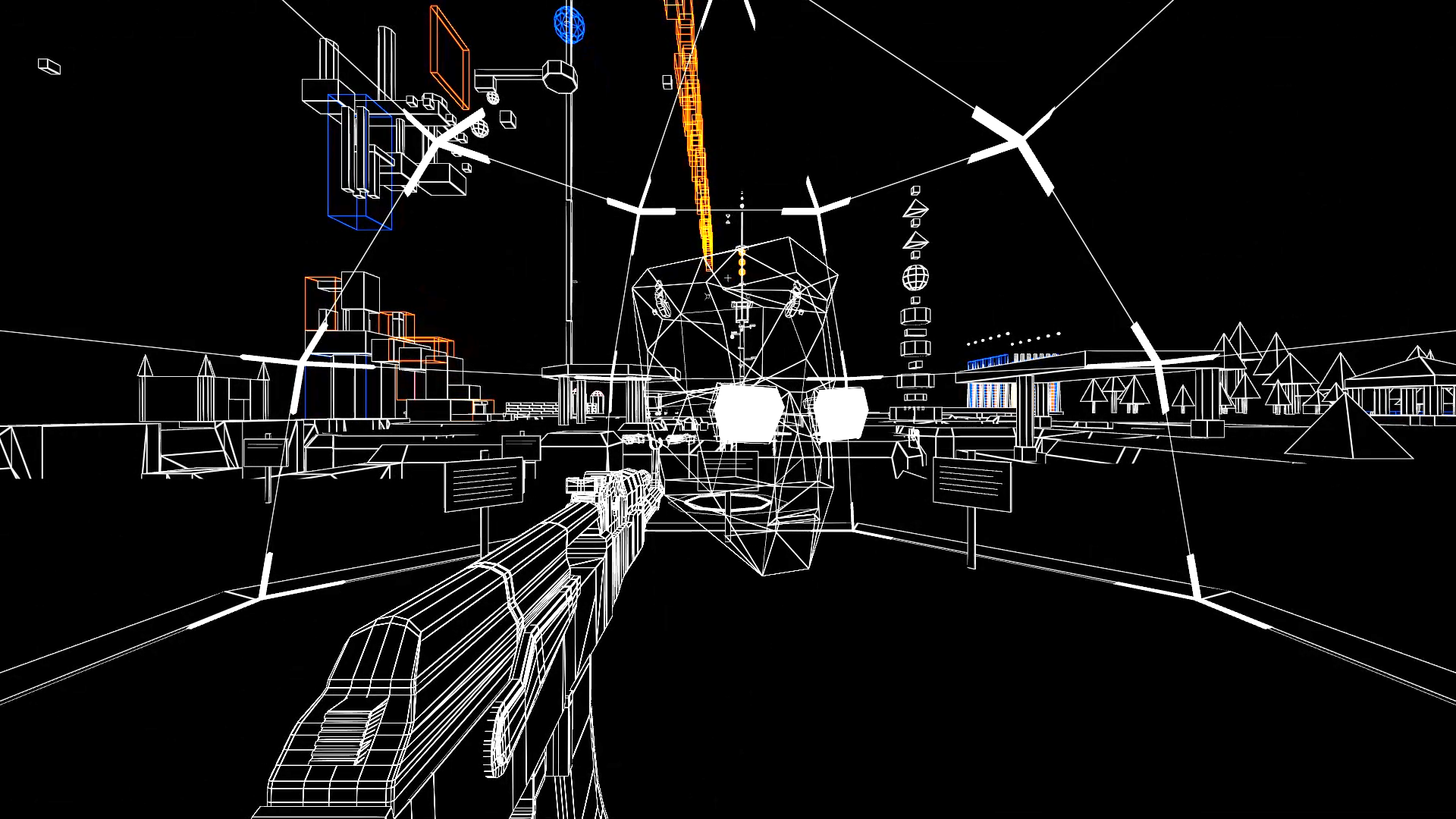

Milan: More than anything, it’s an aversion to the games that are trying to be representative. In the case of DUSTNET and Stellations, it’s about having this conception that the game is closer, down to the circuitry… Having an aesthetic that feels like how we imagine computers render environments as wireframes and polygons. Creative abstraction is huge.

Neilson: Abstraction is huge. DUSTNET’s simple aesthetic felt closer to the server’s digital primitivism. Things like map editors of 3D cubes, spheres, and pyramids, or the basic game elements of air, water, lava. Playing with all these Counter-Strike things, where when they stepped into the space of Dust II that they remember from thousands of hours of playing the game, it doesn’t matter that it’s not wireframe. You still intuitively feel the shape and form of the map, even without the texture. That gets down to the idea that these spaces don’t function as their aesthetic rendering. Once you’ve spent enough time in these spaces, you can fill them out. You know the shape of the corner and a hallway, and you can walk through it blindfolded.

Milan: The reason to do it black-and-white, in my case, is that there are features in games where you have UI elements, environments, text. But having linework and letters feels like everything exists in the frame together. The way that Kentucky Route Zero did their single-pixel thin lines and aliased edges. It feels like these things exist in the world together. For me, it’s important to try and feel that the renderer isn’t treating things differently in the game—like the way in DUSTNET, the chat feels like part of the world. Using 3D modeling software, as well as Adobe Illustrator, you have all these little outlines, and selectors, and wireframes—sometimes I look at that in the creative tool and think, “I want that to be how the game looks.”

Neilson: The game engine defines the style. When you play Counter-Strike, you are actually playing the deeper meta game of the Source Engine. Gabe Newell said something like, “The only company we’ve ever met that kind of kicks our ass is our customers.”

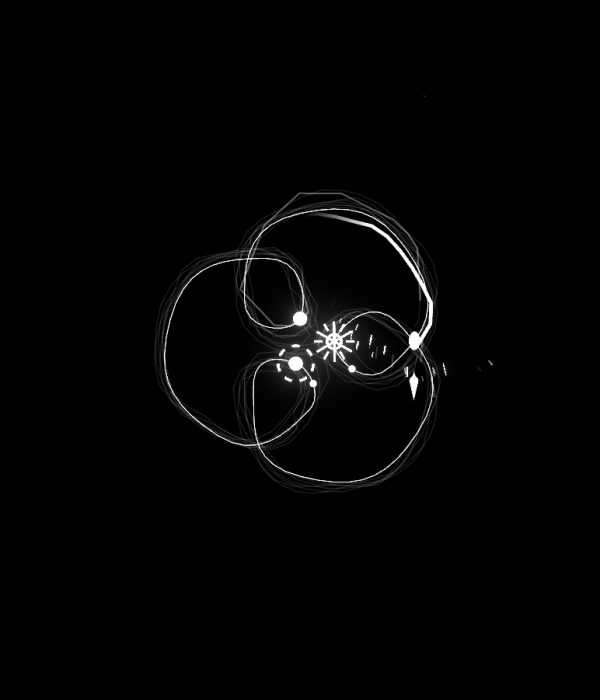

Stellations is a game based on muscle memory and thought loops. How was this project conceived?

Milan: I was thinking about what it was like to be trapped in game worlds. Stellations is about mapping this excessive energy that players bring to games. It’s about trying to look more at the process of play versus the actual goal-oriented play. Going forward, I’m wrapping it in this aesthetic of my maps or feedback loops, diagrammatic language. Still, it’s not about taking those diagrams at face value. It’s about how, by moving through them, you can internalize them. It’s 100% a kinesthetic experience.

I led with the 800 Dash Challenge in Hyper Light Drifter because it was all about this incredible repetitive motion that was synced to a metronome pretty much. At one point, I was playing it with a metronome in the background so I could get the button presses right. That hypnotic element was very compelling to me.

Can you speak more about what you find significant about the emotional connection as one plays a game?

Milan: We both grew up in engaging virtual worlds where you have lots of time and muscle memory and emotions wrapped up in that. There’s a whole generation of people that have grown up like this. There is lots to excavate there with how we’ve got these mental models floating in our head that are entire game worlds. Right now, I’m interested in reverse engineering that process of how people get to that point. In contrast, Neilson’s games have been looking at existing virtual worlds. I’ve had people tell me that with Garden, the experience of being back in Age of Empires is such a loaded gun.

Neilson: You do believe there’s still a mythical element that lives somewhere in the ritual of game engines. I’m not on board with that reification idea… Anyway, Milan told me not to throw too many rocks while standing in a glass house [laughs].

Milan: I was speaking about psychogeographies of games, that’s one thing. I’m interested in thought loops and in the fact that games are this incredibly repetitive medium and wield this repetition so bluntly. I was also interested in poetic relationships between game loops and thought loops. That was my elevator pitch for Stellations—figuring out what that poetic relationship was. I’m still in the process of figuring out. At times I’ve thought about it as games I model, like how we learn and our brains are perfectly mapped to it. The spectrum, when Neilson talks about disenchantment—it’s that games are like a strawman.

They’re another heuristic false consciousness, a way of misunderstanding the world. Whatever the truth is, or whatever particular game model happens to be—that’s not the point. The point is that something is gelling here and that’s what’s important is figuring out the aesthetics of that process. It’s like, why do we get to put on these rails; how do we get hooked into the loop?

Which artists, game designers, studios, and thinkers serve as inspirations for you?

Milan: Minecraft, Starseed Pilgrim, and Tetris allow you to have this discrete navigable world that people shape using the operations in the game. That design paradigm inspires me to no end. Some studios do work that’s more what I like to see in the arts, such as the Playables team—their work has a certain obliqueness. I want to play Promesa as soon as possible. Games where they’re doing stuff that’s not as one-to-one logic, like player input, game output, put it in a spiral. I take inspiration from both camps.

Neilson: We pay respect to the games industry’s true craftsmen who are creating phenomenal design experiences. That’s not our strength or interest.

Milan: Right, I don’t want to make a game where the loop is perfect. I want to make a game where you’re trying to enter into the loop, about the experience of getting there. If I made a game that worked well as a game, I wouldn’t need to think so hard. I like Static by Dennis Carr. He’s a classmate I had at NYU. He made this incredibly loud, abrasive first-person shooter talking about some of the things I want to talk about in Stellations. But instead of flow as the golden promise of fun and challenge, it’s more like flow as anxiety.

Neilson: I look mostly at people outside games still. I like the craftsmen, but video art is my true heart’s calling.

Milan: You like Hito’s videos.

Neilson: Oh, I love Hito. I saw Factory of the Sun in 2015 in Los Angeles. I was blown away. It was the first time I walked into a museum and seen video games, and they were situated as I had never seen them before, all these ideas that were being handled with such grace and witticism and humor. I’ve never seen anything like that before in a gallery. It stuck with me. Factory of the Sun, you can’t find it online. I’m still trying to find a copy.

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity. Interview conducted in October, 2020. Photographs of Neilson by Wade Montpellier, photographs of Milan by David Evan McDowell.