Rachel Rossin: Entropy to Infinity

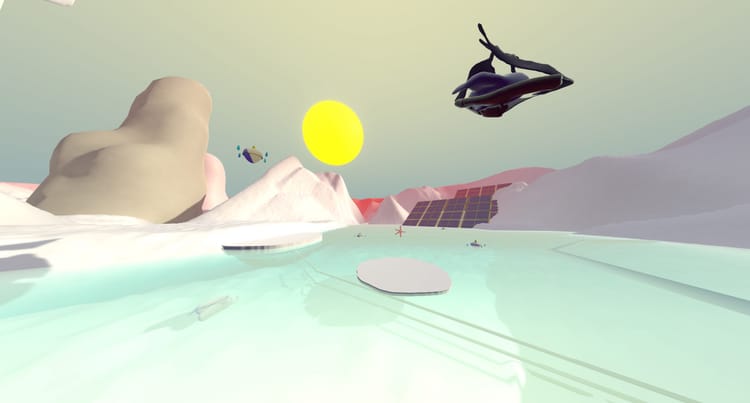

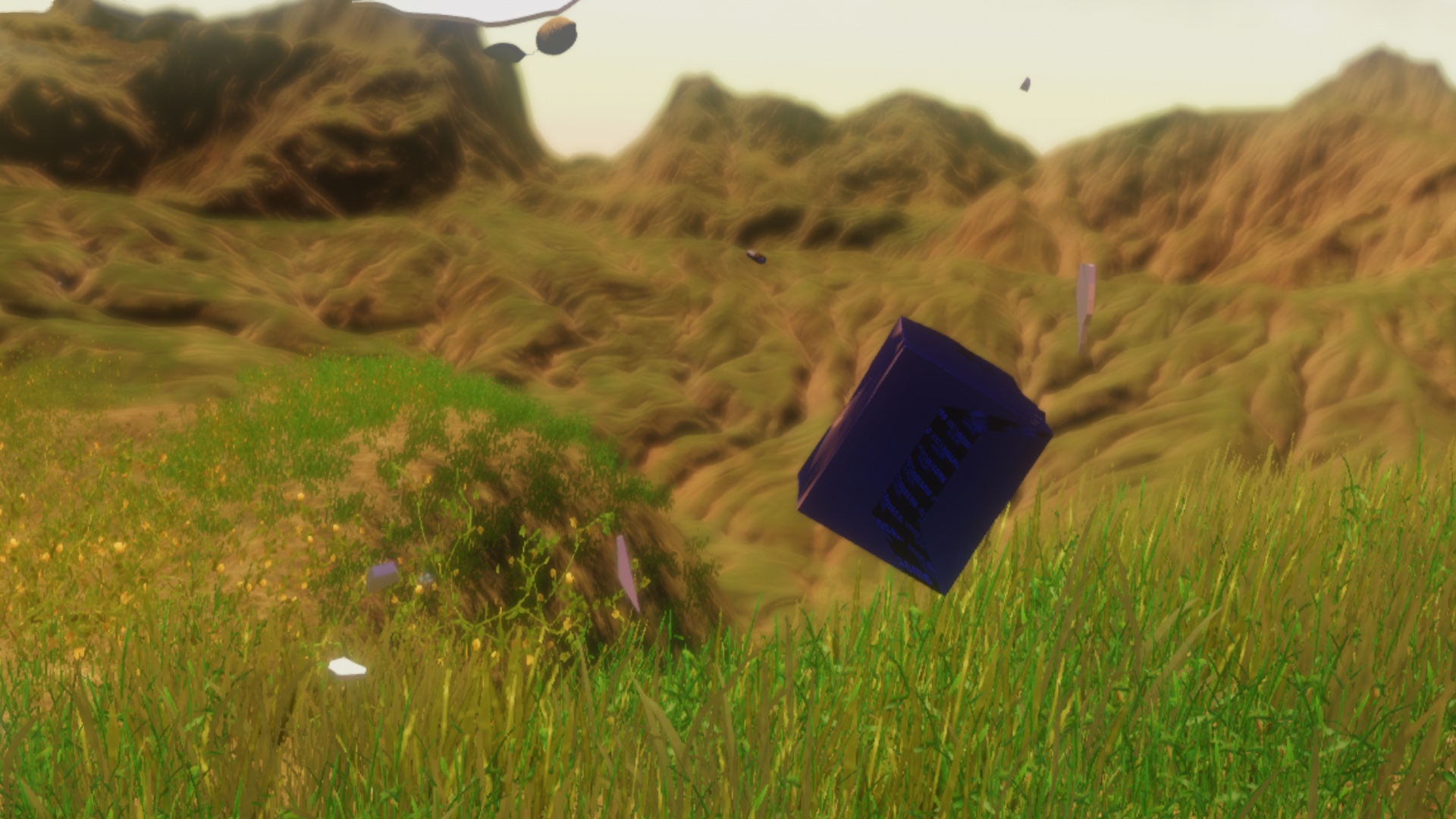

How do we account for the tension between technology’s infinite, unrestricted promise and the impermanence of being human? Rachel Rossin interrogates this slippage. Floating between painting, VR worlds, holograms, and more, the Brooklyn-based artist carries with her the essence of what it means to be alive. Rossin’s work meditates on and pushes the boundaries of human perception, the tenderness, and the vulnerability of empirical experience. Here, she speaks with us on her childhood underwater, the illusory nature of immersive technology, and the need to return to entropy.

Rachel’s new project, I’m my loving memory, is in Rhizome’s traveling show, World on a Wire.

Was there something about growing up in Florida that drew you to virtual worlds?

Many young people are attracted to technology in the first place because there’s usually something to escape from. My community and my home environment were both really intense environments. To cope with that, my young mind went towards spaces that felt safer. There was a very therapeutic necessity.

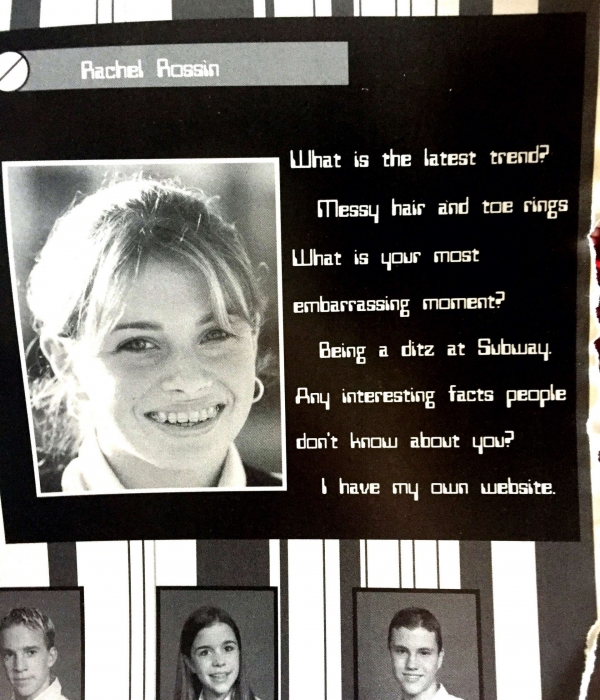

Also, I grew up so close to the ocean and spent a lot of time underwater. It just felt so similar in a way. There’s this thing that was just out of reach beyond this surface. The surface tension of the water felt very similar to the surface tension of the virtual screen. When we first had dial-up internet, I moved into coding and doing small visual experiments online. That’s probably why it felt so native.

My great-grandfather worked as a typewriter mechanic, and then that he was at the Burroughs Adding Machine company. He was a high school dropout— a mechanic when that turned into IBM. He was given a bunch of IBM computers that were then just left in our garage once he died. Those were things that I could tinker with—basically garbage. Especially in the 90s, people didn’t know what to do with something like that. That’s how I started building hardware.

The first experiments were small drawings with the dot matrix printer. I was making shapes on the computer and then printing them out and making drawings. I was also breaking things, doing ASCII art, which I didn’t know at the time. Trying to open the operating system, then I’d have to figure out how to fix it, or I’d get in a lot of trouble. I was fascinated with the world that came with the Windows 95… those maze or pipe screensavers. I was trying to figure out how to make simulated environments.

What was the BFA program like at Florida state? Were there particular professors or classes that helped shaped your practice?

It’s a football school, so the teachers are doing their best—my Professor Owen Mundy showed me Ryan Trecartin’s and Jordan Wolfson’s work. I started to understand that there was a dialogue that was happening with artists that were alive. Before that, I thought that Leonardo da Vinci was the same as Bruce Nauman. For me, there was more access to spaces like DeviantArt or manga.

Luckily, I was encouraged to do experiments, but the program was very separate in the practices. I was secretly making AR experiments with image-based recognition. I would show the painting an image, and it would recognize itself. Those were my first early hybrid works.

You cite Hannah Arendt and Robert Smithson as influences. What draws you to those thinkers?

I think a lot about Gretchen Bender’s and Susan Sontag’s writing. Robert Smithson’s ideas go beyond the novelty of the medium. That’s the essence of all writers that I’m attracted to working in the language of what it means to be human.

I don’t work in the language of technology. When you think about it, technology is the promise of being able to live forever, ideas of utopia. Whereas being human is very much rooted in loss…which, in shorthand for Smithson, is entropy. It’s the tender, vulnerable, and fleshy experience is of being alive. I’m looking for something that’s essential to our lived experience—what it’s like to have a body, what it’s like to lose people that you love, what it’s like to be a part of the messiness and contradictions of that. It goes beyond the medium. That’s why those people are compasses.

When you were starting out working with these ideas, were there biases in the technology that you had to get around?

I look at where the most resistance is and try to press on that. I think about the piece Man Mask, which was this piece where I led a body awareness meditation from inside an avatar I hacked from Call of Duty. With Lauren Cornell, who curated that series, I was talking about this experience of pretending to be male because it was just easier to hide in plain sight instead of being harassed. Looking back on those experiences, I was thinking, where are the pressure points or the points of pain, where’s the knot in the muscle?

With virtual reality, when I made Ghost Hand, I felt like there wasn’t enough. People were putting on these bubbles on their heads, and they weren’t able to express their embodiment—they’re on these rides. So to combat that, I was having the user scrape part of the piece away as they burrowed through it.

With all technologies and media in general, the most interesting thing for the medium usually is the thing it’s most suited for. The question that I had was, why was I using virtual reality? If I was just using it as a novelty or trick, there was no point if I was just going to be making something that could be a film. They wanted 360 videos for the virtual reality piece because of the app’s constraints and the amount of money they had. They couldn’t really host interactive things.

The reason a lot of new media work never touches people is that they get seduced by the novelty or the newness of something without expressing anything that comes from its core.

For projects where you have both a digital and a physical component, are there challenges in the translation that you come up against? Do you think about moving between these two spaces as translation?

Form follows function. So much of the way that I’m working or making the reference images for the paintings or just any of that is in a virtual space.

It’s the same way that you’d make a maquette. I’m using a lot of 3D software already. It’s quite easy for that to be the kombucha starter for what the other parts of the piece will be. It’s the most effective way to communicate on that level is to show the different facets of the practice. It’s pretty natural.

For Stalking the Trace, the presentation at the Zabludowicz Collection, I wanted the video piece on the outside and the structure of the installation to feel like the lobby or the waiting room or the opening to the VR work. That was a challenge because there’s no way to elegantly program interactive things in the physical space. To solve that, I used the zoetrope format, so that when you walked around physically in that area, there would be the illusion of a before or after image or walking through what felt like an animation device. It was an optical illusion—a sleight of the hand.

That worked nicely for me because it’s talking about the body—the inherent frailty and how easy it is to fool ourselves into believing that all we need is an accelerometer in this virtual world. VR is very different from what it is to be in reality. We all know that because of how uncomfortable it is to have a headset on.

That was a nice way of talking about the guts of the piece; the sleight-of-hand of what a lot of visual-based technologies are doing to us.

You spoke about control and freedom on your end for Stalking the Trace. Was that something you were thinking about for the participant too?

The thing about these larger-than-life immersive installations is that there is a sensationalism built into it that lends itself to the user being overwhelmed. It’s the reason the video piece in Stalking the Trace is 15 minutes long. It’s the way that I’m controlling the user’s attention. There are a lot of these hotspots in the video.

There’s a Baton that moves around the outside of the piece, which relates to the virtual reality piece. As the users move around, there are these after images that are happening every now and then, so there’s the element of surprise and seduction of what these big immersive installations bring. You see that in really high production commercial installations—so overwhelming the user or at first, and then in the alleyways, it’s quiet. That was the intention in the presentation of the work.

Is there a binary between observation and embodiment that you’re trying to collapse?

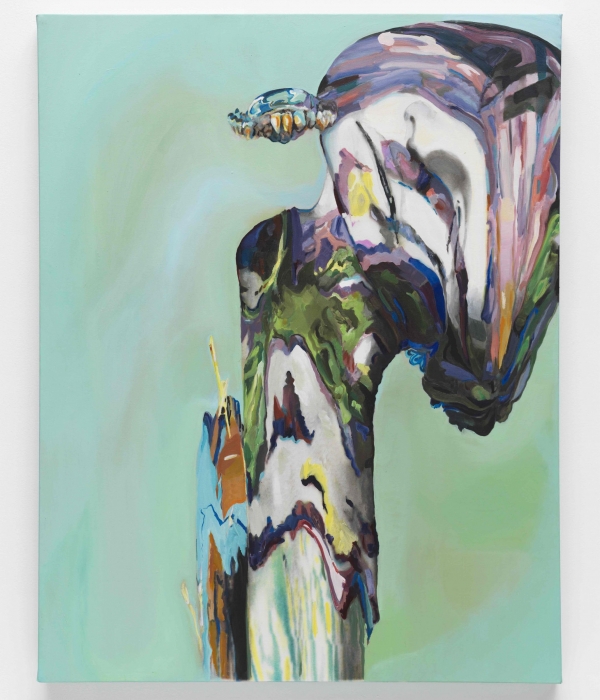

When I’m starting paintings, I do an exercise called recursive live drawing. You sit with your body in virtual reality. If I’m stuck on a problem, what I’ll do is I try to draw or represent the body the way it, the way it feels instead of the way it looks. I can feel when I do a scan really fast. It’s like, For some reason, the backs of my lungs are more prominent than the rest of the body, so it’s like drawing. And how do I express that? This very internal space that’s really based on recursion or using the language of technology to understand something further.

Your process involves the physical act of painting or the corporeal experience of existing in a virtual environment. Could you talk more about the body and corporeal movements as important to you?

Time moves differently in the virtual world. I love programming, the puzzles in making something interactive. Most of the interactive pieces that I make always have the user or the viewer as the arbiter. So in The Sky is a Gap, the viewpoint and the physical position of the user drove the piece. It was tracking the viewer’s gaze and progress to move time forwards and backward, for instance. The viewer’s gaze acts as this entropy laser eating away parts of the piece. You would leave the piece with a different experience—there’s this element of the interactive work, this intrinsic human quality, of what it is to move through space.

When it comes to the painting, it teeters into a seesaw where the work influences itself or each respective aspect. It literally becomes, what is painting? It’s marking my own time and my perspective. When you learn how to read a painting, you can see where the painter is standing. You can see the way that they’re moving through time, based on the style they have, but then it becomes very literally about embodiment.

When I’m working in those spaces, the arbiter is myself instead of the viewer. The hologram combines become these annotations or windows in an even more literal way, like filters layered on top of the paintings. The holograms combine what’s happening in a lot of my interactive works as tone poems. That’s exactly what the works are about—the relationship between the perception of this fleshy, vulnerable thing, and then this idea of infinity, which is totally a farce.

Credits

Interview conducted in February 2020. Edited and condensed for clarity.

Links

Follow Rachel on Instagram