A hungry digital chicken, a living room made of trash, an armed My Little Pony figurine. The work of UK-raised, US-based new media artist Neil Mendoza reaches into the digital realm from the physical, combining sculptural objects and software systems to provoke humor, nostalgia, and reflection on the ecosystems that govern us.

Mendoza has taught courses on art and technology at Stanford University and UCLA. He has exhibited at the Barbican Center, Kinetica, Minnesota Street Projects, and has worked with clients such as Adidas, Nokia, and Wired Magazine.

When did you start to find your voice in creative coding—combining art with technology?

When I was in high school, I was into sculpture and making stuff with clay. When I went to university, I studied math and computer science. I didn’t know you could do creative, ‘art-y’ stuff with technology. The course I did was very theoretical.

After that, I ended up doing various things: working with computers for a video game company, doing web design—working for a bank, even. At one point, I was working for an advertising agency, and I saw someone there working with Processing. I got inspired, realizing that there was a whole world of creative coding and electronics I didn’t know about. So I started playing around, making art installations on my own.

My first publicly-shown art piece in 2009 was a big, physical piece [built] around a multi-touch interface—before multi-touch was a thing on phones.

Then in 2014, I got my MFA at UCLA. After graduate school, I started to think about the conceptual elements of my work more. When you’re making art with technology, it’s easy to get trapped in technical rabbit holes—to spend more time working out how to do a thing at the expense of why you’re doing it and what it should look like.

What is your creative process like? Do you start with a message that you want to convey and then find a way to convey it through an absurd use of technology? Or do you reverse engineer it?

I’ll start with the technology or a movement that appeals to me from a purely dynamic or aesthetic point of view, and build from there. For instance, I made a piece called the “Hamster Powered Hamster Drawing Machine” which started with a fascination for creating a drawing machine where the drawing was encoded mechanically. Then it’s like, okay, what’s it going to draw? It’s going to draw a hamster. Then it’s like okay, why a hamster? Because it’s going to have a hamster powering it and be a self portrait machine . Why should only human beings have access to selfies?

I think it might make more sense to work from a place of ideas rather than making. Although with the way my mind works, I like to be hands-on, to be building things. It helps subconscious ideas to come out when my hands are creating stuff but my brain is whirring along in the background, trying to work out what the thing I’m making means to me.

There’s also a sense of humor that arises when watching your machines re-contextualize human actions, especially when they seem to fumble or act in surprising ways. How would you characterize the playfulness of your work, and why is it important for your pieces to possess a distinct sense of humor?

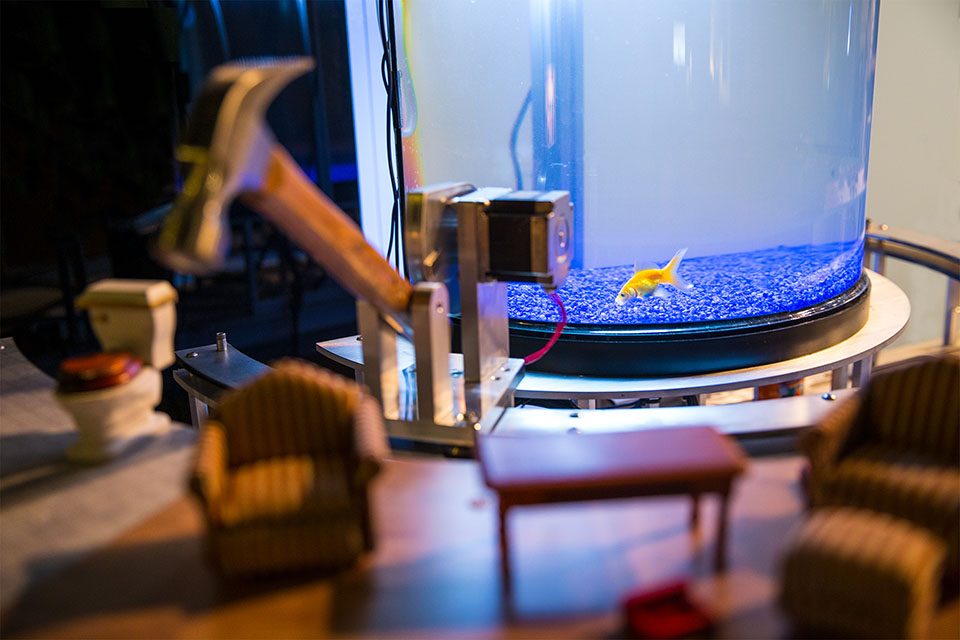

I don’t start out with an explicit intention of giving them a sense of humor. But maybe humor lets you address some slightly darker, more uncomfortable topics. I have a project called “Fish Hammer” that empowers a fish to smash up human habitats. Humans spend a lot of time destroying fish habitats.

When you create work that explicitly addresses these types of topics, it can feel didactic. When you have this off-kilter, fluid approach, it sticks with people longer. I’m interested in using humor and absurdity as a gateway into the psyche. Modern life is absurd, but we don’t see the absurdity of it because we’re caught up in it.

Your pieces leave room for randomness, entropy, or even audience input as a variable. How do you mediate between designing these pieces with a specific intent but still leaving the space for [chance]?

If you want to keep people’s attention, there has to be this tension of not knowing about what’s going to happen. People are good at figuring out how systems work. You see it a lot with “magic-mirror,” interactive installations. People work out what the system does, and once they’ve done that, they’re tired of it pretty quickly.

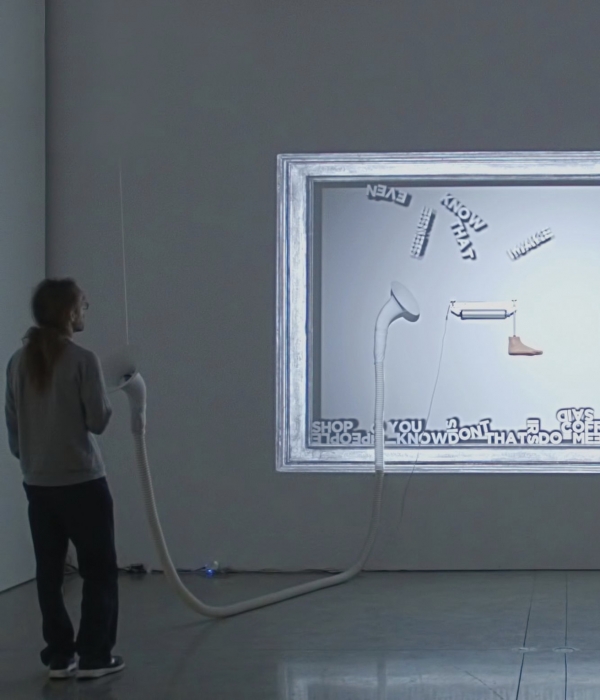

I like having this entropy, this randomness. In some of my pieces, the random variables are quite simple. I made a piece that you speak into, and your words become a part of a projection mapping. Your projected words and then interact with the real-life robotic foot and get ‘kicked’ occasionally. That was a nice example of creating a simple system that people can interact with in unpredictable ways. Some want to have political messaging, some want to fill it with swear words. Above all, it’s nice co-creating with your audience—even as the artist, you don’t know where it’s going to go.

A lot of your pieces are centered around iconic objects—the rocks in Rock Band, the fish in Fish Hammer, the toys in The Ponytron, for instance. How do you identify which objects to add to your creative lexicon?

Objects that have a place in my heart appeal to me. Maybe it’s stuff I was into as a kid, or that seems to me to be ingrained in my psyche. If you choose objects that are already in people’s psyche, it’s easier to connect to them. Then you hijack that connection and get them to think in different ways through this relationship they already have. I worked on a printer orchestra once—and I feel like people connected to that because the printers were from the 80s and they occupied a place of nostalgia in people’s hearts.

I like objects that people have already an interesting relationship with. I can subvert that relationship a little in order to connect with them more deeply. In addition, iconic and funny objects appeal to me…things that maybe you might find Wile E Coyote making traps out of for Road Runner or something you might find in Monty Python or a Terry Gilliam cartoon.

I wanted to ask about your residency at Recology San Francisco. What was the process behind scavenging for these materials, and where would you go to source all of your resources?

The residency gives you a studio, a stipend, and access to the PRRA (Public Reuse and Recycling Area)—where people drop off old technology, furniture, and building materials. They give a training course on how to safely scavenge. It’s a crazy environment because you’re surrounded by all these earth movers pushing trash into a huge mountain.

You’re only allowed to go to the side of the mountain and pick stuff up. If you’re not at the trash mountain when something awesome arrives, it gets crushed into oblivion. Because we were in San Francisco, there was some insane trash—I found drones and 3D printers and computers. For example, one of the pieces I made there was a musical living room—I was looking for specific objects like an 80s television or horrible, kitschy looking couch. It was a sobering experience as well to see how much perfectly good stuff ended up there, cast off. The discovery process was the thing that guided me most.

What are the more challenging aspects of working on projects that span multiple media? You’ve got work that is based on coding, but other parts of the process require your hands and physical input.

The physical part is the most challenging. If you’ve designed something in software and there’s a bug, you can change a couple of lines of code, and it’s fixed. If you have a physical bug, maybe you need to redesign your mechanism, or order some parts and wait. It’s a slower process.

When I’m making something physical, I like to be away from the computer as much as possible and work with my hands. It’s like trying to strike a balance between the process that is going to inspire you to make the best product, but that’s also engineered well enough to stand up to use and abuse by viewers. I find stuff I make digitally, like designed in Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and then fabricate, tends to be able to stand up to use. Often, however, that process can take away some aspects of creativity.

What is valuable about representing these that could technically be conveyed digitally as physical objects, pieces that people can see and interact with in person?

It’s about engaging more senses than just people’s eyes. As soon as you create something that’s purely on a screen, you’re using the same medium that people use for everything else in their life—social networking, email, spreadsheets. As a result, you become part of this homogenized landscape.

It’s hard to make something lasting if it’s purely digital because it’s so easy to access digital content nowadays. It’s worthy content for a couple of seconds and then… it disappears. I like making things that have a life beyond the screen.

I’m interested in using humor and absurdity as a gateway into the psyche. Modern life is absurd, but we don’t see the absurdity of it because we’re caught up in it.

I wanted to talk about the piece “Robotic Voice Activated Word Kicking Machine” that you mentioned earlier, which references customer service chatbots and automated vocal programs.

Alexa, Google Home, Siri—all of these smart systems are now on our devices. It’s easy to think that you’re just talking to a friend and they’re just answering back and being helpful. In reality, though, it’s disappearing into the cloud, being sucked up by their servers and used for whatever ends they see fit.

My piece is a physical manifestation of that. You speak—and rather than the piece answering back, your words are sucked into this other world where they’re possibly abused by this robot’s foot. In short, it’s a manifestation of this phenomenon we have of speaking to digital assistance; forgetting that our words are disappearing into some corporate servers somewhere.

On the growing presence of automated smart technologies in our lives, where do you think things are headed?

At the moment, it seems to be going to a slightly dark place. These technologies are being used to manipulate politics and maximize corporate profit, often at the expense of worker rights and data privacy. I hope that we start on a slightly less profit-driven path. There’s exciting stuff happening with technology, though. It’s got amazing and also dark potential.

I hope that we manage to break out of this ‘device addiction’ stage of technology; that it helps rather than hinders our daily lives. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to go both ways with that, too—it could enhance our experience of the world, but it could also be something that you spend the whole day distracted by.

To sum up, I think It’s important for artists to have a role in where it’s going to go. Unlike companies, their driving motivation isn’t profit—it’s experimenting with these systems and seeing where the edges are, what unexpected things they might do. Humanizing these systems is another area ripe for artistic exploration. On the flip side, art can be a useful tool in bringing the dark side of these systems to light.

Credits

Edited for clarity and length.

Interview by Paolo Yumol in December, 2019.

Photography by David Evan McDowell.