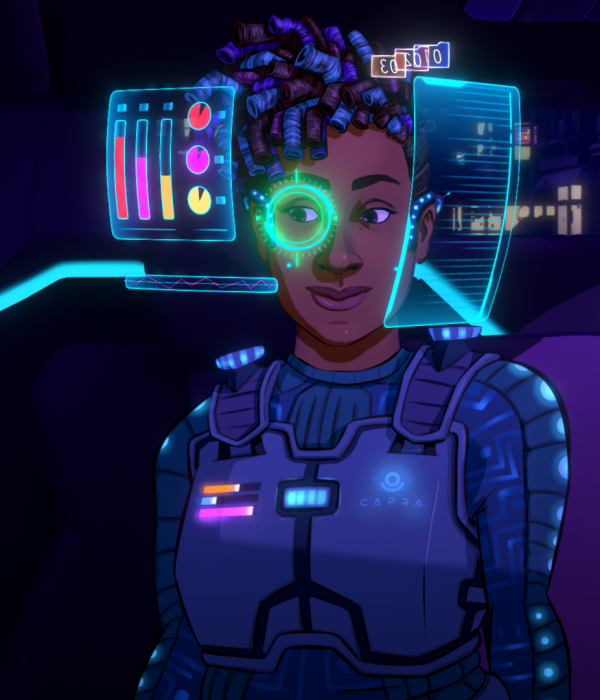

In Neo Cab, you play as a Lina, a rideshare driver navigating a future city. As she picks up passengers and converses with them, she has a biofeedback device that tells her how she’s feeling throughout. But when her friend goes missing, talking to passengers is all that she has.

When we ask writer Paula Rogers to describe Neo Cab, she uses an interesting turn of phrase: “emotional survival.” In many video games, your health and resources are limited or are the currency you use to navigate your world. But for Rogers, it was more interesting to explore the interior life of the characters that she and her team breathed to life.

We spoke to Paula in her Austin home about writing science fiction for the first time, harnessing the conflicts in the gig economy, and what makes a good ending.

How did you get involved with writing for Neo Cab? You have a background in writing with KQED, and Salon, and NPR—how did you make that jump over into writing for a game?

I have been a writer for almost 15 years now and dabbled in a lot of different things. I moved to Austin to get my master’s degree at UT in screenwriting. I had a lot of experience with writing and different formats, and narrative as well. That really helped me with dialogue, and I really learned about that approach to storytelling. I was working in screenwriting stuff, doing freelance writing, and a friend of mine from art school, Vincent Perea, was the art director on the game.

My screenwriting and editorial background are super focused on structure, but I didn’t have a lot of actual game experience. This is the first game that I worked on, and then also I hadn’t played a lot of games. I really didn’t know that there was this whole world of sophisticated narrative games happening. That was a blessing, and also gave me a bit of a learning curve. It was interesting to apply the editorial principles that I’d had for years into this new medium.

For Neo Cab, we had a really unique setup where we have a massive cast of characters. We have Lina, our protagonist, our main antagonist, and then we have about 20 passengers, or “pax,” that you pick up and meet through the course of the game. We wanted Los Ojos to really feel like a city. We wanted those to be people from any walk of life that you could conceivably meet, and so that meant we had to have a really diverse writer’s room. We wanted to bring as many voices and perspectives as possible through the pax, and to make Lina seem like a real, well-rounded person.

I put together the character bible for Lina, for the antagonists, and worked with Patrick [Ewing], our creative lead for Neo Cab, on the story structure and the plot. Then in the narrative design, we parceled out the rides and how we’re going to do the plot development throughout the game. And then, I would assign characters to the writers, or they would come to Patrick and me with ideas for characters.

We would say, “Hey, we need a character that fits this kind of a blank. Writers, give us your best pitches.” We had guidelines for what the rides would be and what the length would be. We would say, okay, yes, we do have room for a person that worships a worm. That became Agonon, written by Robin Sloan.

I had to really work to make sure that she wasn’t just a character that lived in my head. I had to make sure that she was real to the writers as well, so they could internalize her voice, and feel some ownership.

Our thesis of the whole game is “stay human,” which is how empathy and humanity are increasingly threatened with the rise of AI and tech-driven economics. How can we show how terrible things could get if we don’t protect those things? So it was like, no, let’s just take that thesis, and go one level lower. How do you stay human in romance, in religion, in economics, in masculinity? All of those characters started from this conceptual place, and every character began with the thesis. What do they need? What’s their bio that we might never even see in the game? We wanted them to feel like real people.

“This tech-driven race to the bottom is a trend that we’re all very concerned about, and it was a natural place to start.”

Can you tell me a little bit about what you were hoping to say about the relationship that we have to labor, and what that might look like in the near future?

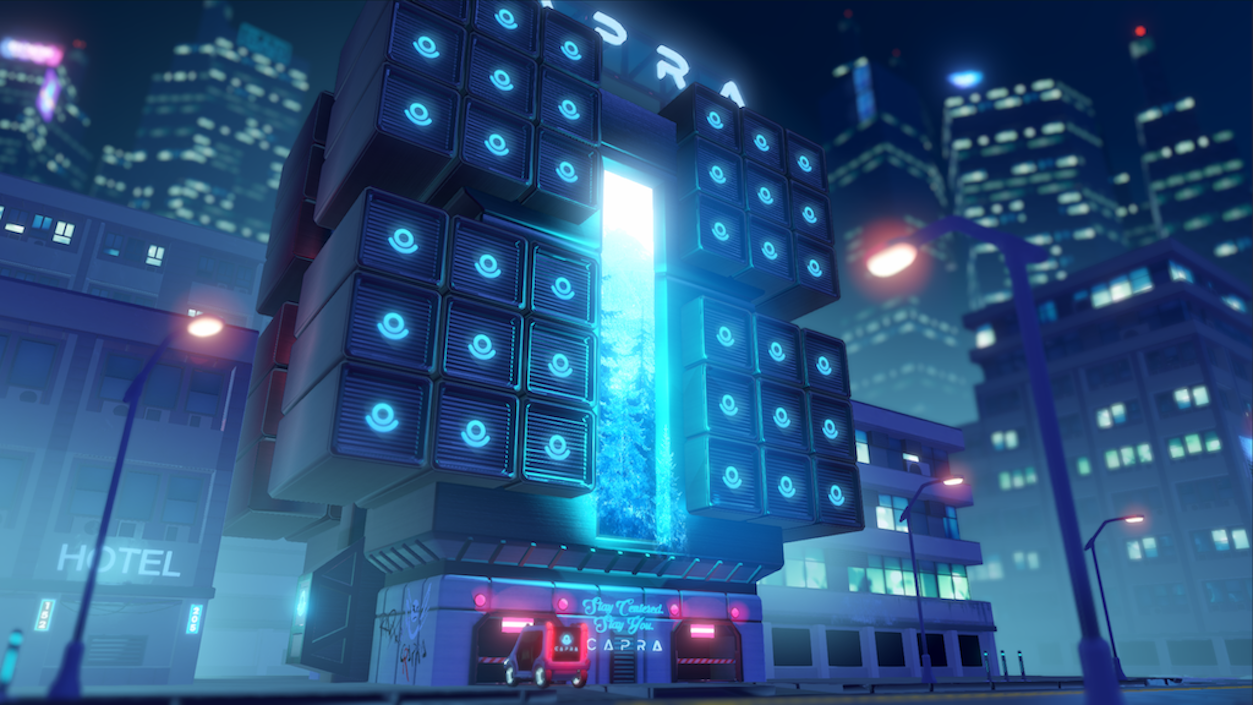

Our comment on the gig economy was that we really wanted to fight the idea that companies like Uber, or in our fictional world, Capra, have, that a human driver could be replaced by an AI driver—and it would make no difference.

So Lina is a human driver in this city that’s being overtaken by AI self-driving cars. What does that mean for her? The passengers that seek her out do so because they crave human connection, and the humanity of Lina, at least as her conversation, her empathy, provides this vital service that people can’t get elsewhere. We wanted to comment on the emotional labor involved in the gig economy.

Lina’s job, even if it seems like it’s just a gig, is very replaceable. But it’s deeply personal to her, and to her experience. Everything that she’s bringing from her life into that moment—you can’t put a price on it. It’s incredibly valuable, and it gets overlooked in this economy where it’s about asking: how quickly can we do something? How cheaply can we do something? This tech-driven race to the bottom, in terms of wages, and valuing labor is a trend that we’re all very concerned about, and it just was a natural place to start telling that story through.

I read a lot of science fiction, but I had never written science fiction before. I always had really liked it, but I read some classics like Ray Bradbury. I didn’t read cyberpunk because I didn’t want to be influenced too much by it.

I had written a lot of historical fiction, though, and I realized that they’re similar. I’m just researching forwards instead of researching backward. I looked up the projected census data for 2050. What will the population look like? That’s interesting. Where will people be living? I read a study on the future of dating, and they’ve projected what they thought dating apps will be like in 30 years.

It was a little scary.

How do the characters that you pick up, how does it affect the final storyline, and how much of that is communicated to the players in advance?

There’s actually a ton of branching in Neo Cab. It’s a hundred thousand words roughly. Everyone gets a very different experience based on which pax you pick up, and every pax has three parts to their story. You don’t have to complete the arc of each pax, but you can, and so that affects who you meet. My brain is getting scrambled, just talking about it again.

It was this labyrinth of so many characters and so many options of who you could pick up at any given time. But we have these essential plot moments that you have to hit.

If Lina’s too happy, sometimes options are closed off to her. That’s the main mechanic of trying to navigate her emotional labor and protect her while also giving the pax what they want to get that five-star rating. And so, you can definitely say the wrong thing to pax. We did an audit close to the end of the game where we were like, how many endings does this ride have? How hard is it? Is it a three-star ride, or five-star? Is it a five star, and a one-star?

There’s definitely a good ending and a bad ending. The good ending is difficult to get, but it involves Lina learning her big character lessons.

Is that what you’re hoping that players will walk away with? That the good endings are hard to find?

I think so. I mean, I hope that’s not mean.

Credits

Interview conducted by Jamin Warren on December 19, 2019. Edited for clarity and length. Photography by Julie Thompson.