Jack of all trades, master of…all of them?

Navid and Vassiliki Khonsari are co-founders of iNK Stories, a Brooklyn-based immersive entertainment studio. At a time when mediums are converging, the Khonsaris are perfectly equipped to take advantage of the new world as they straddle the line between traditional cinematic storytelling and interactive design. As a result, they’ve earned notice and praise from technologists, game designers, and filmmakers with awards and nominations from Facebook, Sundance, Tribeca, and BAFTA.

“We’re developing TV shows, film, virtual reality, augmented reality,” Navid says. “We let the story take the medium rather than pigeonholing ourselves.” Their newest work Fire Escape is a thriller driven by your wandering eye.

We spoke to the Khonsari’s about merging mediums, telling real stories, and search for “ecstatic truth.”

Could you both tell me a little bit about your respective backgrounds in storytelling and interactivity?

Vassiliki: I studied cultural anthropology and film, and I got my master’s in visual anthropology in the UK. My interest was always in using different platforms to convey cultural information and close those cultural perspective gaps between other individuals being the storyteller and the audience and using various forms for that. I started at The New York Times Television here in New York City, then moved into the more feature doc world for Discovery, TLC, VH1, and all those things.

I ended up directing and producing a couple of documentary feature docs about the human condition in niche worlds. One of the documentaries was called Bang the Machine in ’99. Ee thought we were documenting the end of the arcade era, but we were actually documenting the birth of esports. That was about the best Street Fighter players in the US.

That film was all of the live audio and Super 16 on film. All of the audio was in our office, which was across from Building Two of the World Trade Center.

9/11 hit.

The office was basically incinerated, and so we lost the audio, and the film didn’t really have a future, unfortunately. Navid and I met each other, and he was coming from the world of the games, and we founded iNK Stories. The DNA for iNK Stories was always pulling together the ethos that Navid picked up working at Rockstar Games and engaging a broad commercial audience and combining that with an anthropological documentary approach of looking at the human condition. How could we pull the two together and really usher in the next wave for games telling real stories and really emphasizing people, but not losing the fun entertainment factor? How do we bring the best of all of these disciplines and worlds together to push on the boundaries of the platforms we’re exploring and experimenting with?

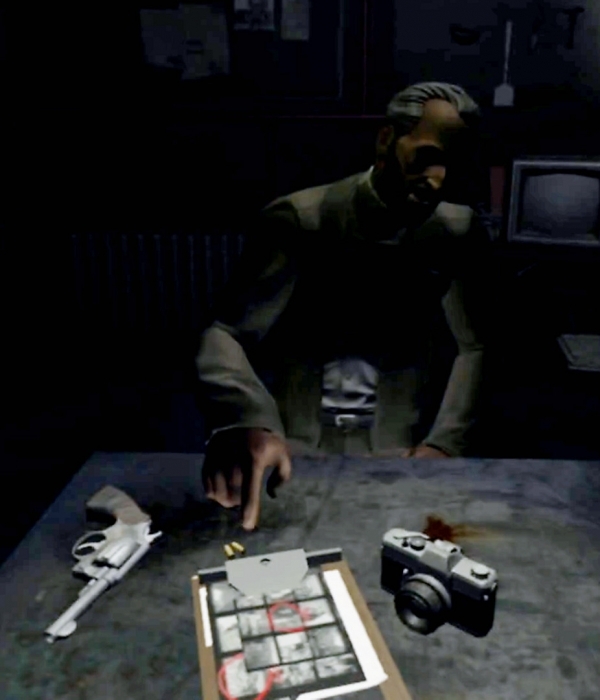

Navid: I graduated from film school and shot my first indie feature in the late ’90s. I had a foundation for cinematic storytelling, which is what opened the door for my opportunity to work at Rockstar and come on board as the cinematic director for Grand Theft Auto trilogy in the PS2 generation for GTA III, Vice City, and San Andreas.

I was the cinematic director and the head of production. I got this incredible experience while the company was just growing exponentially and got to work with A-list talent as well as a multitude of development teams across the globe.

It was a phenomenal experience, and I decided to go back to my film roots after having done an extensive amount of work with Rockstar. Vassiliki and I met and worked on a couple of feature documentaries together. I was able to grow with the storytelling methods in the upcoming, updated hardware generation.

I grew up in Iran and felt that the subject matter of what took place between this country that’s quite polarized with the US. But this really intimate relationship had not yet been told through the medium, and nobody was actually backing a game as the medium to tell stories that are depicting real events and real people.

I wanted to talk a little bit more about iNK Stories’ mission. Whether documenting the Syrian civil war, the Iranian Revolution, gentrification in Brooklyn—your work evokes plenty of overtly political themes and things that are often relevant to phenomena that are occurring in the present. How do you settle on the subject matter for your work, and what kinds of stories interest you?

Vassiliki: As a collective, we work as a narrative writing room developing user experience, game mechanics as part and parcel of story and narrative development simultaneously. What we all have in common is —not to sound corny—but we want the world to be a better place.

We dive into the human condition and look at critical matters and allow people to complicate the truth; to not deliver with the same black and white messaging that we see so often represented in media. How can we complicate our understanding and not underestimate our audiences? We see that in games and films: The audiences are way more sophisticated than a lot of the content allows for.

We want to be that little pebble in someone’s shoe, but at the same time, bring them that aha moment.

Navid: For us, we are looking to bring about pivotal stories to audiences who are yearning for something different. But also, we’re coming from the key pillars that have made games like Grand Theft Auto successful: to entertain, to engage, and to have that high production value.

Could you please tell me a little bit more about Hero?

Navid: Hero is a location-based experience that puts you on the streets of Syria. It allows you to take in that world, not for the single images that have bombarded us through the press of the devastation, to actually show us in parts of the world suffering from the proxy wars and the civil war.

The Syrian people are no different than us in terms of their daily activities. They need to eat. They need to drink. They embrace their neighbors. We wanted you to take all the way that in with a devastating attack. When everything settles and everything that you felt on your skin, the heat, the sense of smell, you’re asked to go and help that one young girl who you’ve become friends with.

In that process, the technology, the graphics, all of those aspects melt away. And you are in it. In the end, you’re asked to save this young girl. What will you do to help this young woman?:

Vassiliki: It’s not a piece with an agenda, it’s a universal human story. It’s looking at the shape of civilian violence and the responsibility that we have as human beings to connect with one another.

Why do you want it to be this location-based experience with robust audio and haptic design?

Vassiliki: At the time, Syria was in the news, and there was decided compassion fatigue where you would read these atrocities in the news. There were a number of documentaries, news clips. And yet, it felt like it just became part of the backdrop of the world we’re engaging with.

At the time, over 70,000 barrel bombs were dropped in Syria. We were thinking, how can we actually take something that people feel like they get it and have this experiential design to allow people to understand. That was both our challenge, and I think what turned into our opportunity.

What were some of the specific challenges you’d faced in designing this experience, especially when compared to the experience of creating your past work?

Vassiliki: My background as an anthropologist means we are really, really concerned with authenticity and representation, so we worked with Syrian refugees. We did a number of interviews with them in a collaborative way, devising the actual narrative of the experience. And in doing so, we motion-captured Syrian actors and also did 3D scans of the refugees, so they’re actually populating the world.

Part of the challenge is when you’re working with sensitive material, there is a lot of R&D. You want to make sure that you are setting out with good intentions and not ultimately creating something that’s a misery machine. The experience has to be able to capture this higher universal truth of what you’re going after.

Leaning into Werner Herzog, our motto of the company is we’re not accountants of the truth. We were after the ecstatic version of the truth. And so I think that was the more conceptual story challenge.

Navid: You do have a responsibility as you take people through this journey. As a storyteller, you also have an obligation to provide them with the ability to see that there is hope, that there is a call to action, and that we can bring about a change.