Videogames enter the post-WASD era

This piece is part of our Future of Genre series. Read more here.

///

“No other game form has that amazing sense of immersion and immediacy—the direct mapping of your perception onto the avatar creates a really powerful emotional link. The sense of being there is incredibly strong. In terms of atmospheric, immersive experiences, you can’t beat first-person games.” –Daniel Pinchbeck, Dear Esther, Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs

In the film essay “The Birth of a New Avant-Barde: La Camera-Stylo,” Alexandre Astruc wrote that cinema is “a form in which an artist can express his thoughts, however abstract they might be, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel.” He was writing about the coming French New Wave, the film movement we most associate with Jean-Luc Godard, which took the basic structure of previous French film as a starting point, then broke all the rules.

“Something particularly useful about the first-person perspective is the ability to get very close to the environment. That up-close communion with the game world allows incredible detail to emerge. The tools we give the player are for getting even closer—crouching down, zooming in, picking up objects and examining them. Removing all barriers between the player and the game world can yield incredible experiential benefits.” –Steve Gaynor, Gone Home

But Astruc could have been writing about any disorganized group of hungry young artists loosely unified by a common ideal of breaking from tradition. The surrealists, the beats, the early punk rockers like New York Dolls and the Stooges. He could have been writing about some people making games today. Although many of these people would deny being part of a movement (Ian Dallas, creator of the first-person-painter The Unfinished Swan, in fact did), they have something in common. Namely, they loosen the first-person perspective from the vicious cycle of 1. Point gun at dude, 2. Shoot dude in face, 3. Rinse and repeat.

“Once you make the player a camera-operator, you’re giving them the freedom to frame scenes and objects in pleasing ways. You’re giving them subjective control of how they put themselves in the scene. They’re putting on a performance for themselves. They’re the audience. They’re one of the cast. And they’re the co-director.” –Ed Key, Proteus

These are games that take the “W,” “A,” “S,” and “D” keys—those four keys around the homerow that feel so natural when steering a loaded gun—and do the unexpected. They’ve tossed aside decades of work by the game industry at perfecting everything we’ve come to take for granted from a smoothly running shooter. Instead of first-person shooters, these are simply games that operate in the first-person, reshaping the silicon into experiences that are post-dude, post-gun, post-WASD.

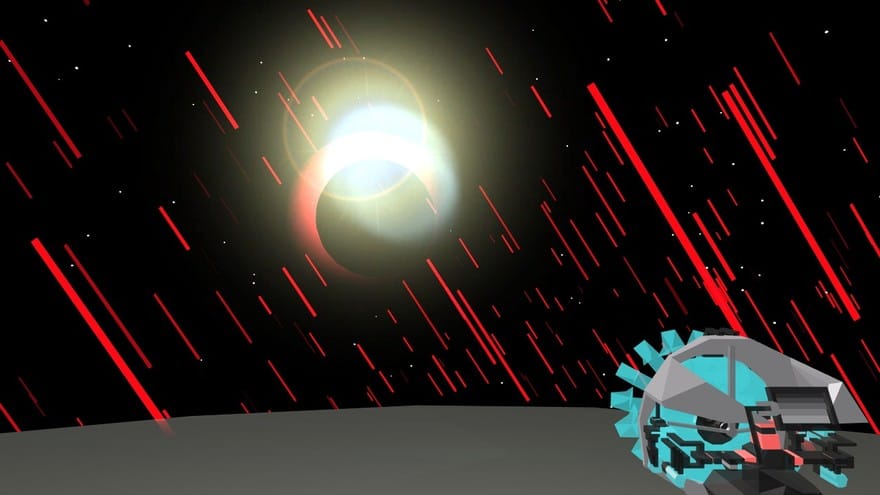

“The gun is a device to invite players to something they feel accustomed to, and then to subvert their expectations completely. It does shoot, but not the way you’d think. On the other hand, it really doesn’t look like a gun. We redid the gun three times making it less and less gun-like in the process.” –Pietro Righi Riva, MirrorMoon EP

Historically speaking, the WASD keys came into popular use sometime after 1996 with Quake. The configuration is said to have been popularized by Dennis “Thresh” Fong, the Michael Jordan of pro gaming. Quake defaulted movement to the arrow keys, but because Fong reconfigured the keyboard to use WASD to run and strafe, and because he was the best, other players copied the position of his hands. Over the years, many keys have vied for WASD’s prominence, but failed: ESDF, DCAS, IJKL, IJKM. Left right AZ, anybody?

“First-person exploration is a bit more compelling than other control schemes because small inputs on the part of the player create large changes to what’s on screen. Rotating the camera up five degrees, for example, is enough to change every single pixel on-screen.” –Ian Dallas, The Unfinished Swan

Post-WASD games have little in common with each other aside from wanting to explore more nuanced emotions than the adrenaline surge of war. The Stanley Parable is self-referential and metafictional, poking holes in the illusions we actively ignore in games. Dear Esther is singularly concerned with pensive mood. Amnesia wants to scare the shit out of you, and finds that that’s a lot easier when you don’t have a huge freakin’ gun. Gone Home takes narrative conventions of the first-person shooter—the one where audio logs and environmental clues tell the story—and turns them into something personal and touching.

“From an artistic standpoint, Antichamber was a game about the player themselves and what information they are trying to process on the screen, rather than being about the character the player was controlling.” –Alexander Bruce, Antichamber

Apart these games are disparate, each doing their own thing, but together they clearly show that the first-person can do more than just target practice. When you have a warm gun in your imaginary palm, you see the world through the mechanism of that gun. But when the gun is removed, or replaced with something else—a rubber duck, a splash of paint, a gun that shoots portals instead of bullets—the possibilities are limitless.

“There are basically endless manipulations of space-time behaviors, the sense in which the environment is dynamic and ‘alive.’” –David Kanaga, Proteus

One question is: why now? Post-WASD games could be a reaction by creators who are dissatisfied with the range of experiences offered in mainstream shooters like Call of Duty and Battlefield. Like many of us, they have shooter fatigue. But maybe it’s best not to think of them as reactionary, but as a broadening—a further step away from the old formalist reading of videogames, which says you have to kill bad guys, and score points to win, and shoot guns.

///

Header by Zach Kugler