On the Level is a series that closely analyzes individual videogame sections, examining how small moments in games can resonate throughout—and beyond—the games themselves.

///

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare‘s (2007) writers understand brevity. Each loading screen provides a satellite image of the upcoming mission, accompanied by a terse overview. “Good news first,” explains SAS operative Gaz, before the opening level. “We’ve got a civil war in Russia … 15,000 nukes at stake.” It’s graceful. Like a soldier, on standby for mission go, while the player waits for action, she sits through an intelligence briefing. It’s economical, too. If you can use them for exposition, why leave your loading screens empty?

Not that the game’s loading screens are always filled with dialogue. On the contrary, Modern Warfare‘s third level, “The Coup,” opens on an eerily quiet God’s-eye view. “Car inbound,” says one anonymous observer, as the camera follows a moving white dot. “Continue tracking,” replies another. Compared to the levels before it, which were explained to the player directly, “The Coup” begins with an ambiguity. Stephen Barton’s foreboding score, the conversation between two analysts, and the satellite image of a Middle-Eastern city are enough to tell us something is going on—but until the camera flickers and blacks out, and then spirals down to ground level, we don’t know precisely what. It’s subtle, but it perfectly sets the level’s tone. This loading screen is not like what has come before. There begins a sense of unease.

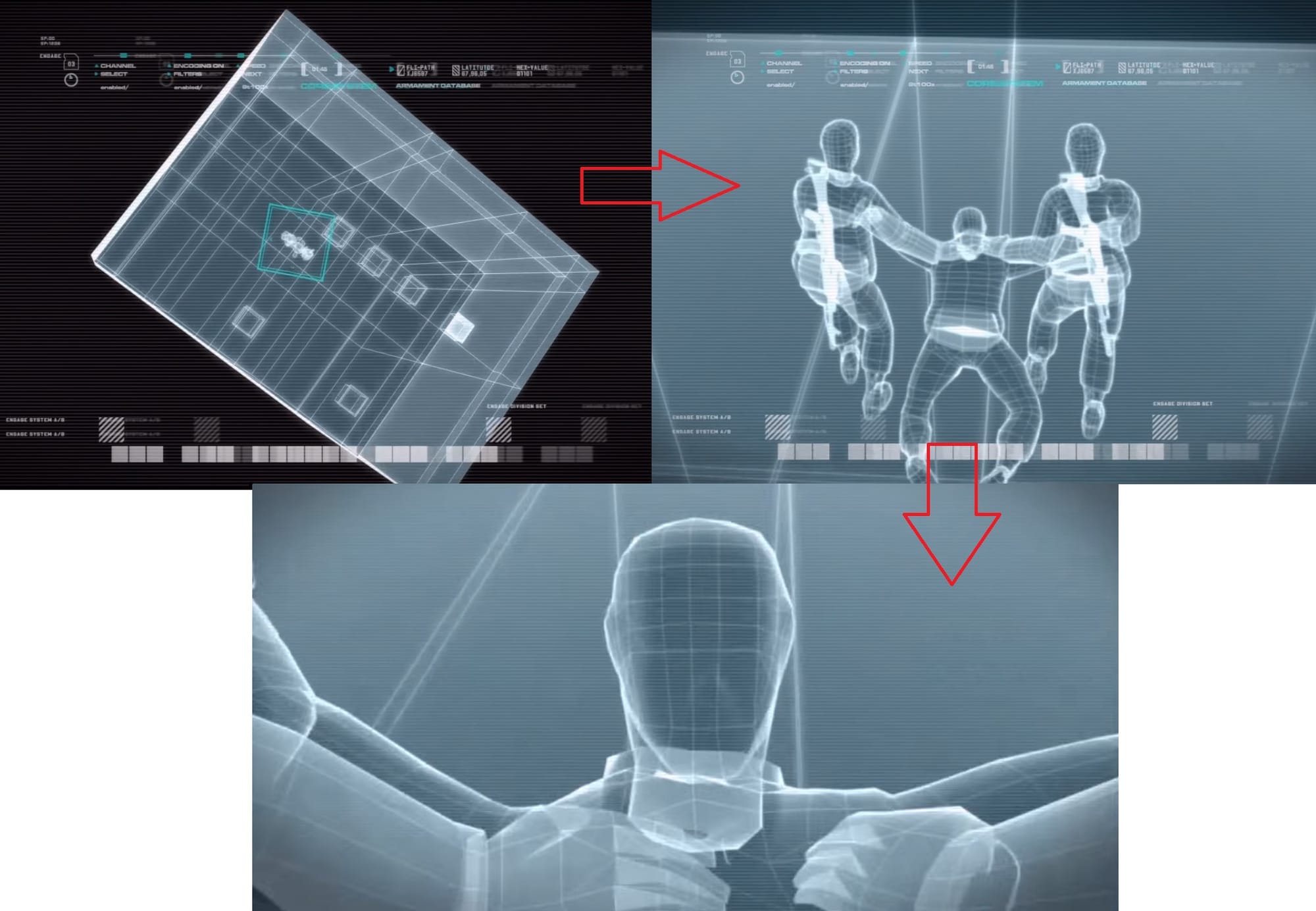

Throughout Modern Warfare we change perspectives, playing either as SAS trooper John “Soap” MacTavish, US Marine Paul Jackson or, in a series of flashback missions, Soap’s commanding officer Captain Price. When we are first introduced to each of these characters, the loading screen simply cuts straight to their first-person perspective: straight away, when the action starts, we are inhabiting their bodies and looking through their eyes. However, when “The Coup” finishes loading, we follow—with the camera—down from the satellite view and into a building, staying on the loading screen until it physically enters the head of Yasir Al-Fulani, the deposed president of Modern Warfare‘s nameless, pseudo Middle-Eastern country.

It’s time to pay attention

To be literally steered into his body—for the camera to force its way into his head, rather than simply cut to a first-person perspective—alerts us to the fact that we are about to be shown is noteworthy. This particular first-person perspective is not to be taken for granted: by carrying us from a dispassionate, out-of-context satellite image into the very eyes of Al-Fulani, Modern Warfare impresses that we are being given a privileged view. The eyes are important here. It’s time to pay attention.

We are also made to feel like outsiders. Playing soldier is a typical videogame experience. Being an overthrown, Middle-Eastern president is not. By positioning us as interlopers into Al-Fulani’s perspective and, by extension, the civil war enveloping his country, “The Coup” impresses that our comprehension is limited. Perhaps this particular war, in which we will be once again fighting in as virtual soldier, is not so clear cut. If “Crew Expendable,” the level directly preceding “The Coup”, made us question the probity of our character and his comrades by showing them executing soldiers who were asleep, “The Coup” itself undermines the sense of absolute understanding that we may typically carry into war shooters. Modern Warfare does not deftly place us into Al-Fulani’s shoes. It forces us in—we are invading this body and for once cannot claim to simply have agency, and thus know every answer and be able to control and predict every outcome.

Subsequently, as Al-Fulani, we are dragged through the courtyard of our (now former) presidential house and thrown into the back seat of a car—doubly ominous, since we recognize it as the car that was being tracked during the loading screen. Driven by one of the revolutionaries (Victor Zakhaev, Modern Warfare‘s tertiary antagonist, is introduced here also, as the man in the passenger seat), the car weaves through the war-torn streets of Al-Fulani’s former rule. What happens outside the car is relatively rote videogame spectacle. Jets fly overhead. Tanks roll down the roads. People shoot at each other. More important is how these scenes are viewed and experienced. The only available action is to turn our head to look through either the rear, front or back windows of the car—as Al-Fulani, held at gunpoint, we cannot move.

At the same time, everything is captured inside a natural frame. The outlines of the car’s windows isolate each moment, reminding us they are distant, that, like looking at a picture on a wall, we are viewing them passively. But not thoughtlessly. What could be a gratuitous sequence (look at all the death and explosions!) is saved by Modern Warfare‘s defining us not only as a passive onlooker, but as a helpless one too. As an interloper, resigned to simply moving the camera, we glare at the chaos. But as Al-Fulani, we’re aware these are our people, our country. Protagonists in Call of Duty are usually barely defined—no voice, no face. In “The Coup”, the lack of a fully-formed sense of character allows us to project our emotions out. We do not fear for Al-Fulani, as, aside from a vessel in whom we are traveling, we do not really know who he is. Similarly, Al-Fulani, gazing through the car windows, rather than pleading with his captors, does not fear for himself. Both player and character seem more concerned for the people outside.

There is no opportunity to, or even a suggestion of, escape

At the level’s finale, when Al-Fulani is dragged from the car, the sense of unease that started to build in the loading screen approaches climax. Initially a foreboding, regular beat, the music reaches a crescendo as our perspective—after having been thrown to the floor—tilts up to reveal a stake, already covered in blood, in the center of an auditorium filled with chanting rebel soldiers. The player and Al-Fulani both have the same realization, but still there is no opportunity to, or even a suggestion of, escape. Later, when the player, as US Marine Sergeant Jackson, crawls out of a wrecked helicopter after being caught in a nuclear explosion, there is a sense of struggle. Though Jackson eventually succumbs to his wounds and the screen fades to white (thus signaling the Call of Duty trend of killing at least one playable soldier per game), he makes a noble effort to live. Modern Warfare is a game filled with action and movement—even as our character lays dying, we can still move him around. And so the ability to only move Al-Fulani’s head, even when faced with certain death, lends to “The Coup” a sense of resignation and melancholy. Al-Fulani and his regime, patently, are both finished.

And why not? While Al-Fulani remains a mute, passive and observing character, rebel leader Al-Asad gives a spirited and rousing speech to his troops. The specifics of this revolution are never revealed (despite implying Al-Fulani’s dismay for his people, Modern Warfare never confirms he was a good leader) but certainly, in “The Coup”’s closing sequence, you understand why the rebels have won. Dressed in red, marching around the execution floor and yelling into a TV camera, Al-Asad is a dynamic presence. Al-Fulani, especially considering how little the player can move him, is comparatively flaccid—one gets the sense his government has been in power far too long. There is, however, a small twist in this sequence. As well as Al-Asad, the execution floor is occupied by the hitherto unidentified Imran Zakhaev. A tall, bearded man in a long coat, when Zakhaev stares directly into Al-Fulani’s eyes, you get the sense he is the one really in charge. The way he hands the gun to Al-Asad confirms it.

Rather than give it to him grip first, Zakhaev points the gun straight at Al-Asad’s chest. It’s the smallest of animations, but the rebel leader, for a split second, stops dead in his tracks, obviously intimidated. Again, we see how economically Modern Warfare is written. Rather than explaining that Al-Asad is being manipulated, the writers, in the briefest and most naturalistic of instances, show it. Later, when it’s revealed Al-Asad was merely an underling and the true antagonist is Zakhaev, it’s still an unexpected turn in the plot but not arbitrary. “The Coup”, in its final moments—even before Al-Asad puts the gun between Al-Fulani’s eyes and, with a bang, the screen cuts to black—sets up Modern Warfare‘s villains.

Almost reluctantly, “The Coup” pulls us into the head of Al-Fulani. The spiraling camera pan in the loading screen, compared to the flash cuts at the start of the rest of Modern Warfare‘s levels, represents labored movement, as if we are being dragged into somewhere. With the precedent set—you are an invader, looking outward—“The Coup” directs our attention to the chaos around us, using in-world frames and limited interactivity to tell us that we can only look, not touch. With Al-Fulani’s unresisting death, the level ends on an appropriately pensive note. At the same time, the implied back and forth between Zakhaev and Al-Asad hints at the intrigue, drama, and excitement to come. It’s the set up for a game which, more than its predecessors, values both great, action spectacle and small moments of player and character introspection. There will be times, later on in Modern Warfare, where characters do shocking things. “The Coup”, by forcing us into a position where we are trying to comprehend violent and alien circumstances, opens our minds to those subsequent events.