The dice come to a stop with eight pips showing. I move past Go and collect additional resources. But then I end on a property owned by an opponent and I have to pay him his due. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it? But this isn’t Monopoly, and I’m not controlling a mere thimble. I am the powerful Hastur and on my next turn I will get my revenge.

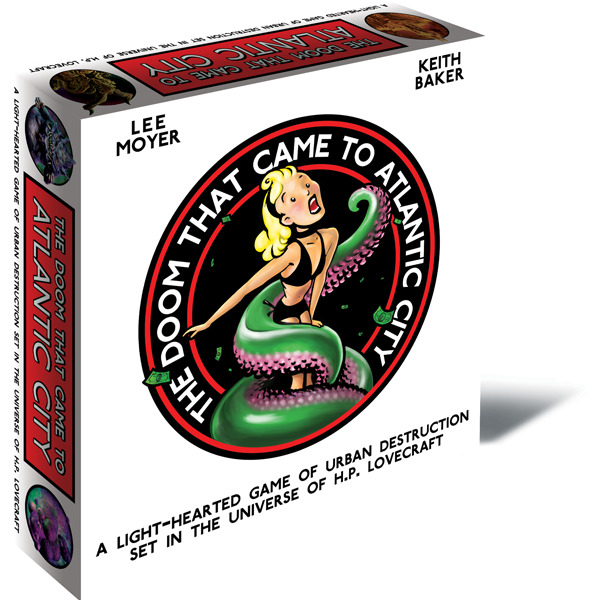

The Doom That Came to Atlantic City is a new boardgame being published by Cryptozoic Entertainment. The creation of the game by Lee Moyer and Keith Baker is a twisty story, but it is finally seeing the light. The backers of the project on Kickstarter will be getting their copies later this month and it should reach stores not long after. The box labels Doom as, “A light-hearted game of urban destruction set in the universe of H.P. Lovecraft.” But when it comes down to it, the game is a Lovecraftian take on Monopoly, a comment on and send-up of the venerable boardgame.

The Doom That Came to Atlantic City is a new boardgame being published by Cryptozoic Entertainment. The creation of the game by Lee Moyer and Keith Baker is a twisty story, but it is finally seeing the light. The backers of the project on Kickstarter will be getting their copies later this month and it should reach stores not long after. The box labels Doom as, “A light-hearted game of urban destruction set in the universe of H.P. Lovecraft.” But when it comes down to it, the game is a Lovecraftian take on Monopoly, a comment on and send-up of the venerable boardgame.

There is the familiar square board with properties; the names and colors have been changed, but it is still the familiar streets from our childhoods. But rather than going around buying the properties and building houses, the player controls a Great Old One from H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction, and you are destroying the homes there, opening gates to the outer planes on the razed land. In the meantime, as you travel the colorful squares, you are fighting the other players for more cultists, using infernal powers on each other, and breaking all the rules to the original real-estate game.

The thing that may stand out for most players is a change that makes Doom feel more modern than the venerable Monopoly. It is not a passive game where players only influence each other via paying rent when they land on each other’s properties. Players near each other can attack one another in Doom, resolving the battle with dice rolls. They can also use Chants or Providence cards against one another, the analogues for Chance or Community Chest cards. A player could wind up having three Providence powers and several Chants cards to use in one fight, with his opponents hectically tossing out their own cards to try to survive. This insanity can be overwhelming.

And rather than playing a game that can last hours and hours as you try to bankrupt each other, the game ends when a player controls six properties with their gates. Someone with only six properties in Monopoly would likely lose the game. Players also randomly get a Doom card, which also provides another way for them to end the game, such as having four gates and sacrificing 12 cultists, for example. Which is all good for your own goals, but what the other three players are working toward can be a lot to keep track off.

Besides reducing the number of hours you are simply going around the square, you also don’t need to go to just walk around the board. Beyond movement from rolling the dice, you can also teleport around the board using gates. These can be your gates, an opponent’s gates, or even the neutral gates that replace Monopoly‘s railroads. This freedom seems like a blessing compared to simply moving the spaces indicated by the dice, but eventually you have too many choices and you can find yourself bouncing around like a madman.

And most importantly, Doom is not about money. Whereas Monopoly is all about collecting the all-mighty dollar, the resources players use in Doom are the cultists they have enthralled or the house tokens collected from wiping them off of the board’s properties. This isn’t a game about bankruptcy and foreclosures. It’s about wrecking the city and ruining the other players. And such destruction is fun, but there are almost too many outlets for it and not enough focus on building a coherent strategy.

Doom may start simple like Monopoly, as everyone moves around the board collecting resources. But it doesn’t take too long for players to gain cards to hurt one another, accumulate powers, and open gates across the board. Soon, when a player rolls the dice, through the use of teleporting between these gates and the powers they have gained, they may have a choice of six or even more spots to end up on, easily avoiding the lands controlled by opponents. And then players will furiously play cards on each other, trying to stop one another. It becomes a chaotic and sometimes confused game, which may actually hurt it compared to the almost zen singlemindedness of Monopoly. Such is the danger, though, when one toys with Cthulu.