“To be alive is to travel ceaselessly between the real and the imaginary, and mongrel form is about exact an emblem as I can conceive for the unsolvable mystery at the centre of identity.”

The quotation above is the 217th paragraph of David Shields’ 2010 manifesto Reality Hunger. It may not, however, have been written by Shields. That is because Reality Hunger is made up of quotations and appropriations mixed indecipherably with Shields’ own writing. It is a work about the erasure of the line between fiction and non-fiction and the artistic validity of hoaxes, but the book itself is a mongrel form, built from pieces created by others. I know this because Random House’s lawyers requested Shields, for legal reasons, included the full list of sources from which the book is made up as an appendix. Tucked away among the final pages, this appendix is marked with a “cut here” line to encourage its removal, and is preceded by an introduction in which Shields states: “Stop; don’t read any farther.” However, if I cheat, if I do turn to those forbidden pages in search of the truth, I find no entry for the above quote. This might lead me to assume that it was written by Shields himself—however, the introduction to the appendix also states that Reality Hunger’s reference list excludes, in Shields’ own words, “Any sources I couldn’t find, or forgot along the way.” So the quote remains in flux, unable to be attributed to a stabilizing source. And through this flux, in a strangely self-reflexive way, it becomes the subject of its own claim—that to be alive, to exist, is to travel ceaselessly between the real and the imaginary.

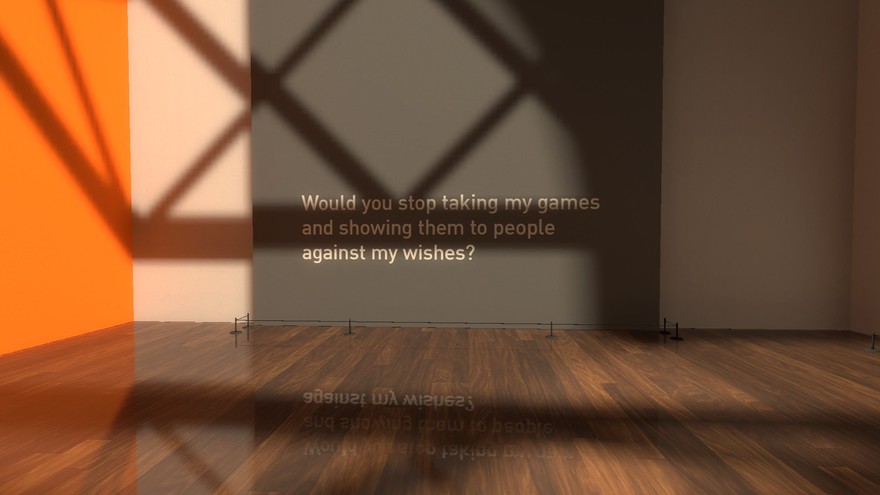

Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide exists in a similar state. Ostensibly a series of games that Wreden claims to have been created by the untraceable hobbyist developer “Coda,” each segment is presented to the player with dates and details, and a narration that leads her interpretation of each stage. We begin in a crude version of Counter-Strike’s de_dust—perhaps the most iconic multiplayer map in existence. Though appearing to be little more than the result of a half-finished level-design tutorial, Wreden draws our attention to the blocks of colour and floating crates that he insists represent what will come to be Coda’s particular trait—that the obvious crudeness of his constructions indicate that the game was made by someone, and implicate Coda directly into the work. But already, only minutes in, we are wondering, is Coda real? Despite the debates, the claims and the accusations, this is a question that The Beginner’s Guide has absolutely no interest in. Like Shields and his cut-out-and-throw-away list of sources, Wreden is not interested in who made what. He is not interested in tricking us into believing Coda is real, or that we are playing his games. Wreden, like Shields, is interested exclusively in “Reality.” Of course, as Shields points out: “Reality, as Nabokov never got tired of reminding us, is the one word that is meaningless without quotations marks.”

///

To understand Reality Hunger we have to understand its context. For a few decades we have been calling the artworks which resemble it, marked by appropriation, fragmentation and the method of their construction, as postmodern. That term, born in the spatiality of architecture and expanded endlessly by critical theory, has become a kind of catch-all for both contemporary art and life. It has become the singular way to describe the state we live in today—where truth is transient, myths are dead and the individual reigns supreme. Reality Hunger, despite its attributes, is not postmodern—it is an attempt to address the postmodern problem. When all truths have been demolished, when every part has been deconstructed, what comes next? Jean Baudrillard called it “the desert of the real,” the state in which reality fails to be real, replaced by the absolute mimetic fiction of hyperreality. When fiction and nonfiction are equal, there is no reality. Reality Hunger presents the reverse of this logic—when fiction and nonfiction are equal, there is no fiction. What Shields presents, through both his words and those of others, is a desire to build something on the ruins of postmodernism that is energized by transparent illusions, ceaseless autobiography and multiple realities.

There are countless writers who share the same project, who were born into the desert of the real and are desperate to find reality wherever it may exist: the humans-in-systems of David Foster Wallace, the many-layered ephemera of Mark Z. Danielewski, the appropriative readings of Vanessa Place. All have been mislabelled as postmodern; all are exploring existence as a fictional process. Videogames have seemed initially ill-equipped to make the same kind of gestures. Yoked to the creation of entirely unreal spaces, they value fiction above all else, at best managing to engage in their own postmodern processes, winking at the player with limited subtlety. Yet with The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden firmly asserts that games possess their own “reality hunger.” This perhaps should not come as a surprise—Wreden previously worked on one of the most accomplished works of videogame postmodernism, The Stanley Parable. A comically ornate challenge to the idea of player agency, it strips games down to their base systems. Over consecutive playthroughs it takes the fictions of games apart, reducing them to their own desert of the real. With The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden, perhaps in some accelerated version of the literature of the past two decades, begins the process of building on this potent foundation.

///

Initially, The Beginner’s Guide appears to be a work of biography, a portrait of a creator through the games he makes. At no point does this ever cease to be true, and yet it simultaneously fails to describe the complex relationships that the game presents. In Chapter 8, the player is put into a game where notes are left for her to find. Text explains that these notes are left by other users over the internet. However, seconds in, Wreden’s narration tells the player that the game isn’t connected to the internet, and that the messages are all written by Coda. It’s a compelling image: that of a creator writing an entire game worth of fictional messages, engaging in a wide and drifting conversation with himself. It also seems to be a symbolic image, one which represents Wreden and Coda. Whether they are aspects of the same person, or distinct personalities, it doesn’t matter—the game doesn’t allow us to see Coda’s games without the presence of Wreden. He is always there, offering interpretation, help, information. This monologue is self-aware, carefully constructed for the players attention, and yet it also seems reflexive, as if Wreden is witnessing and responding to his own interpretations. The player is unable to speak back, and so the game takes on the aspect of those fake messages, conceited and yet honest, an expression of both a genuine and a constructed self, with inseparable boundaries. If we compare Wreden to The Stanley Parable’s nameless narrator, we suddenly realise how important the ideas of biography and autobiography are to The Beginner’s Guide. The Stanley narrator is “the man behind the curtain,” constantly undermining the game’s sense of meaning, but in The Beginner’s Guide Wreden dictates the game’s meaning, a constructed layer of emotional responses that imbues every space with doubt, intrigue and personality. Like David Foster Wallace and the other writers who are presenting the possibility of a self after postmodernism, this is identity as a fractured mirror, a rejection of coherence that finds realism in inconsistency.

Rather than question Coda, we might as well ask if Davey Wreden is real. The fact that he shares the same name as The Beginner’s Guide creator is a playful semiotic game, much like Ballard in Crash or W.G Sebald’s doppelganger narrator in Rings of Saturn. Both are simultaneously reflections of the author and fabrications of them, resembling their namesakes in the same way that a dance resembles a dancer, or a building resembles an architect. They are language masquerading as personality, just as The Beginner’s Guide’s Wreden is speech masquerading as testimony. This fakery is not in service of a trick, however; it is the thing itself. Wreden uses his lies, his deceit, his hoaxes and his misdirections in service of a kind of truth. It’s a truth that emerges out of autobiography—and yet who can say that Wreden is truly represented in the game? Instead he is bringing focus to the inconsistencies of representation itself, to the inconsistencies of the self. This narrative re-contextualises all of the games in the collection. Every individual game in The Beginner’s Guide is not significant in itself, but is significant in relation to an external reality. Each game is an artifact. It doesn’t matter if they were made by Wreden or Coda, these games are objects in themselves, each with both an internal reality—their systems and rules, and an external reality—their nature as constructed objects, modes of expression, and ultimately, games.

This is the true revelation of The Beginner’s Guide: that games are not just fictional worlds but objects in themselves, that are able to produce and generate layer after layer of possible realities and fictions. All that is required is for games to recognize themselves as objects—not to hide their nature beneath convention and illusion, but to embrace both their crude and sophisticated natures.

///

There is a single moment of The Beginner’s Guide that I find myself being drawn to again and again. It takes place in only the second chapter, a generic first-person-shooter that is comically unfinished. Wreden takes great delight in pointing out how broken it is and, guiding the player to the end of the level, he places them in front of a final choice. A voice takes over, an in-fiction one, pleading with the player to give their life to save them all from the “whisper machine.” It’s a moment of specifically recognizable videogame fiction, designed to lull the player into accepting this world as real. The voice is warm, human, female, and strongly contrasts with the wailing sirens and automated security warnings that have filled the level’s soundscape so far. All the player must do is sacrifice herself by jumping into the beam of the engine. Despite knowing that this is a broken, ill-constructed game, that the player has spent less than a few minutes inside, there is some weight to this choice.

Eventually, we jump in and die. But then Wreden stops everything. He tells us that this death is what was supposed to happen, but, in Coda’s original version of the game, didn’t. We are teleported back outside the room and given the same task. Now the weight of the choice is gone, the unknown nature of what happens next erased. We happily jump into the beam, and something bizarre happens. We begin to float up, out of the level. The sound cuts out and we see the whole map laid out beneath us, encased in what can now be seen as a crude and poor skybox. As we float up Wreden begins to suggest interpretations for this event, that it might represent the afterlife or a sense of futility. He even passes it off as just a glitch. Yet somehow this moment remains irreducible. In this crude game, it is as “real” as the corridors, the announcements, the gun. It is, due to the fact that it is occurring, eminently more real than the titular “whisper machine.” Yet it also remains unreal due to its appearance as a mistake within the game. For anyone who has played any amount of games, it is something that has been codified, through experience, as “not part of the game.” Yet here it is, part of a game, part of a fiction.

There’s a small detail that precedes this moment, one that feels important. As the player passes a window on their way to the engine room, Wreden states, “I love how you can see the bottom of the universe from this room.” Instantly the player goes to the window and looks down, seeing the starscape outside end in a flat gray square. Its an easy joke, but Wreden’s choice of words makes it stick. Why does he say universe, when he could say game? Or level? Minutes later, while the player is floating up, it seems evident that he chose that word because this is a universe, and this particular universe ends in a flat gray square. We can see it with our own eyes, what could be more real? This is not Wreden extending the fiction of the game to include glitches and other errors—this is him destroying the fiction of the game and replacing it with something altogether more real. He is pointing to the mistake, and by doing so he is changing it to a purposeful detail, re-coding noise as signal. In this moment, the game is made real, not through illusion, but through revelation.

///

Reality Hunger, like The Beginner’s Guide, has its own “Coda.” True to the original definition of the word, it is the concluding section of the manifesto, a single stolen paragraph. In what is perhaps a strange coincidence, it seems to mirror the central concept of The Beginner’s Guide as if it were the answer to the puzzle, hidden away in a separate book. It reads as follows:

“Part of what I enjoy in documentary is the sense of banditry. To loot someone else’s life or sentences and make off with a point of view, which is called ‘objective’ because one can make anything into an object by treating it this way, is exciting and dangerous. Let us see who controls the danger.”

Wreden is the bandit of The Beginner’s Guide, looting the life of Coda to construct an argument that is made all the more convincing by its stolen reality. That Coda’s reality is more than likely created by Wreden in the first place does nothing to change that. The above quote reflects that—the construction of the thing is what makes it “objective,” not its source. Wreden, with The Beginner’s Guide, is proposing something that is difficult to find elsewhere in videogames: a reality hunger for the medium. It is not that the game is perfectly constructed, or even without its missteps—it is that it is so clearly committed to the search for the genuine, the real, among the endless and equal fictions that make up our world. Wreden’s game is not a place to disappear into, but a space in which to be seen, to feel more awake, more real. It is an attempt to look at a collection of games as a collection of objects, as real as the water glass on my desk, the mouse beside it, and the book beside that. Each has my fingerprints, and the fingerprints of others. Each can be eminently real, eminently fake. It is not these facts that interest me, but ways in which they can be shown to be true and then false, and then true once more. The Beginner’s Guide shows us that to exist is to be fictional, constructed—and that the fictions which we construct are inescapably real.