Do a quick Google search of “contra.” Browsing the first few pages, you should see a saturation of links about the videogame—the now-primary version of the word—sprinkled with other definitions. Next in the deck is contra as preposition: “against, contrary, or opposed to,” suitingly enough. Then, a “contemporary New York cuisine” restaurant; contra-dancing, a folksy flirty form adaptable to many musical styles; the second album by Vampire Weekend; and eventually, peeking through before being closed out again, you’ll stumble upon the elephant in the room.

Contras are the name of the group of soldiers from Nicaragua that Ronald Reagan cultivated in the 1980s, during the Cold War. They were created specifically to fight the Sandinistas, a socialist political party, who had recently overthrown the right-wing and American puppet dictator, Somoza.

Contra commandas 1987 via Tiomono

Because the American taxpayers weren’t all that jazzed about their money going to foreign soldiers with dubious causes, fighting with doubtlessly corrupt methods—raping, torturing, and kidnapping civilians just a smidgen—the Boland Amendment was legislated between 1982 and 1984 in order to prevent Reagan from overreaching. Except, it didn’t work. The Iran-Contra affair, revealed by Lebanese newspapers, eventually proved that via loopholes in the amendment, a couple soldiers, under Reagan, were still sending funds, albeit “privately,” to the contras, paid for by selling illegal weapons to Iran.

The Iran-Contra affair put an even deeper black mark on Reagan’s record. The public knowledge of it and disapproval of him culminated in late 1986, which raises some questions about the videogame titled Contra, first released for the arcade a few months later in February 1987. Some serious questions.

It should be noted that Konami’s original Japanese title “kontora” was chosen solely to sound like the Western word “contra,” and not because of any particular meaning in its individual syllables, so we know that American translators didn’t take any creative liberties on the title. Europe, however, either used the names Gryzor for various computer ports, or Probotector for the NES one.

It was easy to avoid the nasty political implications of Contra. Actually, Probotector is a portmanteau of “robot” and “protector” changed to match the new eponymous sprites, now less violent and more robotic than humans. Under Germany’s restrictions for the Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young People (BPjM), certain media couldn’t be sold on the basis of being potentially, well, harmful to young people. Also, Gryzor is what Ocean Software (now Atari, inc.) named the first arcade version in PAL regions, likely because it thought Kontora’s literal translation didn’t make any sense; though dodging the awkwardness of witlessly commenting on political controversies at the time shouldn’t be ruled out.

On the surface, the contras in the game only share superficial commonalities with the ones in real life (i.e, they’re both soldiers). In Japan, the game takes place in New Zealand, the year 2633—a relatively innocuous time and location. In the American translation of Contra, however, where the political realities and controversy surely wouldn’t tackle the subject head-on, the opposite is true. It is set somewhere in the Amazon, in the present day, 1987. Those jungle trees and mountains in the background are just as much the geography of Nicaragua as New Zealand. Usually, localization and translation are meant to make a game more palatable, but everything about the American Contra is more spicy.

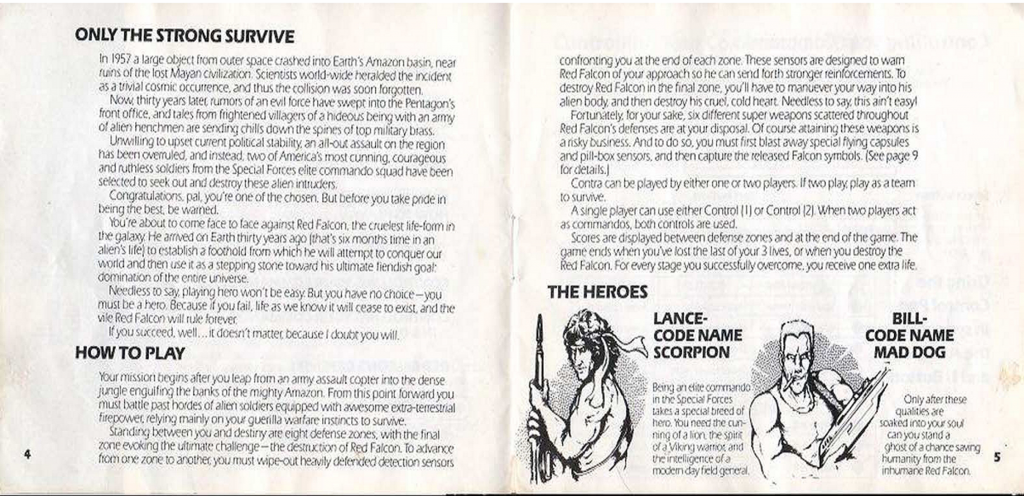

Extract from the American NES manual

Contra, in all its variations of story and aesthetic, tossed from creative hands in different regions and consoles, overwriting story and even art, is something of a homunculus. It’s difficult to talk about because it barely exists in any real pure form. That being said, the American translation, particularly the plot in the instruction booklet appears to interpret the content of the game into something new and subversive: a subtle satire of Reagan fooling around in Nicaragua, and American military expeditions in general.

The game’s plot, described in the American NES manual, as in the excerpt below, reads like a transparent send-up of America’s view of the events in Nicaragua, and more specifically, its black-and-white take on fighting communism in the Cold War.

“In 1957, a large object from outer space crashed into Earth’s Amazon basin, near the ruins of a lost Mayan civilization. Scientists worldwide heralded the incident as a trivial cosmic occurrence, and thus the collision was soon forgotten.”

The Mayan civilization, not located in South America as the manual indicates, existed in rough proximity to modern Nicaragua. The “large object from outer space,” the enemy in the videogame, can be seen as the enemy to the contras in real life, the Sandinistan government. Sandinistas (in Spanish, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, shortened FSLN) naturally opposed to the US, trumpeting anti-imperialism and Marxism. They formed in 1961, which was relatively trivial, until later when the ambitious goals of “seizure of political power” were met.

“Now thirty years later, rumors of an evil force have swept into the Pentagon’s front office and tales from frightened villagers of a hideous being with an army of alien henchman are sending chills down the spines of top military brass.”

The FSLN finally did carve a victory in 1979 over the US surrogate, Somoza; a revolution now known as one of the most significant events in Nicaraguan history. “Rumors of an evil force” also swept into the Pentagon’s office: once the Reagan administration got wind of the Nicaraguan leader supporting Cuban Socialism and leftist El Salvador, he was spurred to fund the opposition and to even directly send CIA soldiers to Nicaragua.

“Unwilling to upset current political stability, an all-out assault on the region has been overruled and instead, two of America’s most cunning, courageous and ruthless soldiers from the Special Forces elite commando squad have been selected to seek out and destroy these alien intruders.”

Ignoring the absurdity of “upsetting political stability” by waging war on an alien literally sent solely to kill humanity, this is almost exactly what Reagan did to contain the spread of socialism in Nicaragua, sending the CIA over to do the dirty work. Except he also hired the contras, the citizens of Nicaragua who didn’t particularly care for their new Sandinista government, due to a variety of reasons, whether that be displaced anti-Sandinistans, or peasants who didn’t get what they were promised. Even, curiously enough, the first two bridges that get destroyed in Contra, iconic to players of the game, have a striking real life parallel. In his book, Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA, 1981-1987, Bob Woodward found that the CIA destroyed two bridges in 1982, near the beginning of the expedition.

The next paragraph of the Contra booklet describes the goals of the antagonist alien, Red Falcon, not at all removed in either semantics (“red,” anyone?), chronology, or rhetoric, of the Cold War.

“You’re about to come face to face against Red Falcon, the cruelest life-form in the galaxy. He arrived on Earth thirty years ago (that is six months time in an alien’s life) to establish a foothold from which he will attempt to conquer our world and then use it as a stepping stone toward his ultimate fiendish goal: domination of the universe.”

The anti-communist scare and Cold War started roughly around 1950, around the same time Red Falcon arrived. Lots of the rhetoric used to describe communists in order to motivate America against the communists were based on unwarranted fears that they would take over the world, stepping on one little third-world country at a time. Just like Red Falcon, the fear was equal parts goofy and apocalyptic.

I don’t even know what to say about the last part:

“If you succeed. well…it doesn’t matter, because I doubt you will.”

Even the aesthetics of Contra represent America, borrowing entirely from macho action films. Look at the original Japanese models for the characters Bill Rizer and Lance Bean. Do you see Nicaraguan soldiers? I see two grizzled, white Hollywood archetypes. In fact, Lance is Sylvester Stallone, drawn at times with quintessential sweatband as Rambo (First Blood, 1982), and Bill is Arnold Schwarzenegger, chewing a cigar, just like in the movie Commando (1985). Even Bob Wakelin, the artist for the NES box art in Europe, brutally observed that this game is a “rip-off” of an American action movie, namely “Alien/Predator.” Even the enemies in Contra are inseparable from Hollywood, inspired by H.R. Giger’s monsters, through Alien (1979).

The dissonance between the title and overtly American content of the game delivers the sharpest criticism: the contras fighting the war are proxies for gung-ho Americans fighting a different one. It lampoons Ronald Reagan’s self-image in the fight against communism during the Cold War. Or, it lampoons the lack of self-awareness one needs to fight an unjust war. Contra raises a clear opinion about the real contra scandal, more precisely on the irresponsibility of Cold War rhetoric in making serious decisions. Made more appropriate given Reagan’s background as an actor, extending the Reagan Doctrine to its logical extreme as an appropriately dumb fantasy movie is an artful way of skewering it.

The American manual could have been orchestrated by a clever translator who re-interpreted an innocent game, inspired by American popular cinema, into a personal joke about the sinful nature of said movies—perhaps cathartically releasing their frustration through an unpopular medium where nobody would raise an eyebrow. Or it could have been the product of the opposite: absolutely no self-awareness about how current events can be sneakily channeled or commented on through seemingly brainless media.

After the game is beaten, the credits roll with the ending theme, composed by Kazuki Muraoka. It sounds about how the ending to a war movie should sound. A little bit triumphant, but a lot stoic, like a toast to victory over one particularly hard mission in the line of millions. It is an epilogue in itself. It is also called Sandinista.

Do a quick Google search of the word “contra” again. Maybe it’s poetic that most people in America today signify the word with the game, rather than reality.