Designing the sound of the impossible

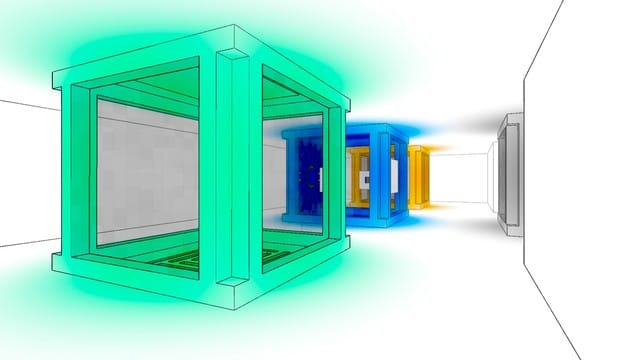

Robin Arnott isn’t known for conventional work. He’s the twisted mastermind behind the terrifying Deep Sea, and the sound designer who is currently celebrating his collaboration with designer Alexander Bruce on the just-released Antichamber. The game is an exercise in non-Euclidian geometry and seriously brain-busting puzzle design, and its currently generating high praise across the gamersphere – not to mention solid sales – it hit the number one spot on Steam the day of release.

I was able to catch up with him not long after the game arrived, to chat about his unusual inspirations, working with Bruce, and the many paralells between sound design and game design.

– – –

Arnott describes Bruce as an “auteur” with “with very strong ideas and a rigorous commitment to the game.” The two shared an intense, iterative creative process focused on marrying the high-contrast visuals and decidedly unnatural locations with an atmosphere that feels earthy and grounded. The result is a mellow, almost Zen soundscape that was inspired more by Dennis Dutton’s TED talk A Darwinian Theory of Beauty than the freaky discomfort of disordered space.

“They’re solved by stepping back and being patient with yourself and letting your brain make the connections that are there.”

“That was absolutely a deliberate design choice.” Says Arnott, of the unusual sound direction. “Alex thinks about audio in a really comprehensive way. I think he’s a great sound designer – that was his idea and it’s one of the strongest sound decisions in the game.”

In fact, the reasoning behind that decision was not to fool players into a false sense of security then slam them with impossible puzzles – it was to keep frustration low and minds open to solutions that will come naturally with experimentation.

“One thing interesting about Antichamber‘s most obtuse puzzles is they’re not solved by thinking about them, or looking harder for an answer, they’re solved by stepping back and being patient with yourself and letting your brain make the connections that are there.”

Arnott sees himself as a game designer by way of sound design, and vice versa. He designs for experience and sensation rather than for “left brain” reasoning, which made him a natural partner for Bruce.

“There are some very weird sound ideas in the game.” He says, mentioning the tibetan-bowl sound you pick up a new gun and the “whispers” of the black tiles. “But everything [besides the tibetan-bowl sound] was the result of an intense back-and-forth between Alex and I. The gun sounds went through more iterations than I can count. Generally, I [would] make something weird, Alex [wouldn’t] like it, so I made something else weird with an updated idea of what Antichamber is. But I always started from somewhere pretty out-there.”

“I don’t think I consciously thought of it in this way, but starting “out there” and then pulling back “in here” helped me really understand the perimeter of what Antichamber wanted to be. It’s like they say about travel giving you a better perspective on your homeland, I think starting all our sound conversations from somewhere surprising helped us – helped me anyway – know the game better. And having a better idea of the bounds of what the game wants to be definitely helped me make bolder choices with confidence that they’d either make the game a little more true to itself, or help me learn more about what the game isn’t.”

Despite the fits and starts, Arnott praises the experience whole-heartedly. For him, it was an intense, rewarding creative exercise.

“Working with Alex was a dream collaboration as a sound designer – I really mean that.”

“If an idea didn’t work, or only kind of worked, it was cut out. We pushed back on each other in an extremely constructive way, and knowing that I’d get that push-back from Alex liberated me to experiment in some really unusual directions because I knew that he had such a strong vision for the game. Experimentation is a process of failure – there are so many failures in Antichamber‘s sound design, but each failure makes the successive results more true to the game. This was an extremely time consuming process, but it paid off beautifully.”

“Lemme give you an example.” He continues. “I make a sound for the riot ball from my roommate playing his guitar in a really weird way. But of course it can’t sound like a guitar – if it sounds like anything recognizable, it’ll carry all the cultural associations with that sound and break the bizarre isolation of the Antichamber world. So I process it a bunch, I try different methods of recording it, I reverse it, blah blah blah. After a day of work, which is a bananas amount of time to spend on a single sound effect, I send it to Alex.

I don’t like it. (by now I’m used to this response). Why don’t you like it? It sounds like a popper toy. It sounds too close to what it looks like. Maybe we should try making it sound like bees. I don’t like bees – bees are scary and nothing else in the game is scary or threatening.

So on the one hand, we decide that I needed to start from scratch. On the other hand, now I know what Antichamber wants to be a little better! From this conversation, we started exploring how the natural-sounding environmental world could blend with the musical-abstract sound of the interactive stuff – and there’s kind of an internal logic that develops for why that makes sense. In a way, I guess making sounds for Antichamber is not that unlike playing Antichamber.”