Designing With Games in Mind

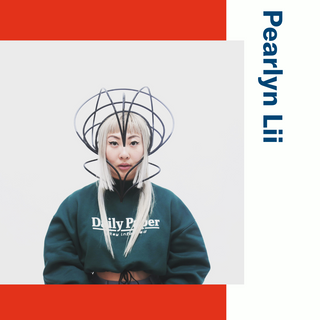

Pearlyn Lii (she/her) started as a graphic designer and quickly built a body of work on various digital forms. In this conversation, we will explore the process of incorporating to gaming as a practice. We'll focus on learning new tools and looking for personal growth.

Lii draws inspiration from performance art and transmedia approaches. We will discuss the importance of starting with a story and understanding the desired outcome before selecting the appropriate tools. Similarly, you can effectively communicate with developers and engineers and ensure the realization of their vision.

Pearlyn will delve into the significance of pre-storyboarding and transitioning from graphic design to gaming for her new project. We will explore how Twitch can serve as valuable source material and discuss techniques to watch for while engaging with gaming streams.

From Online Girlfriends to IRL Intimacy

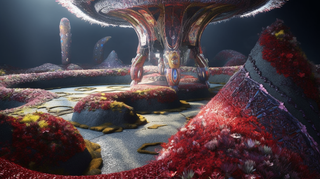

We’ll likewise work through her process of “Real Girlfriend” (2021), a performance-based exploration that takes place in augmented reality (AR). (Read more here on Foundation's site.) Through a series of videos, it offers a satirical critique of prevailing female archetypes, in contrast to what's been constructed through the lens of the male gaze. By amalgamating various women from the virtual canon, the project challenges and deconstructs these archetypes.

We will examine the role of avatars and their portrayal of eye contact in the context i.e. Uncanny Valley. Embracing imperfections and the desire for perfection, we will explore how eye contact can contribute to a deeper understanding and immersion within digital art pieces.

The talk will also touch upon the concept of intimacy in gaming and how platforms like Twitch allow for the expression of different personas and characters. By embodying diverse roles and considering their attire and behavior, creators can enhance their performance and engage with audiences uniquely and captivatingly.

Join us to discover how pivoting to gaming as a practice can unleash your creative potential, guide your tool selection process, and foster immersive storytelling experiences.

About Your Speaker

Pearlyn Lii is an interdisciplinary artist and streamer whose practice investigates personhood, neomythology, and the divine feminine. Her work narrates the plight of the human experience through fictional characters in alternate realities, reinterpreting harmful female archetypes. Drawing from mythology, science, fiction, and magical realism Lii responds to a personal and collective desire for a more regenerative, equitable future. Her work manifests through embodied performances, augmented reality, and video installations.

Lii is an alumna of NEW INC, a cohort of artists supported by The New Museum, and is a selectee of the Art+Code track in partnership with Rhizome. There, she founded nonstudio, an art and design practice that investigates mythologies through transmedia. Her work has been presented at New York Live Arts, New Art City, JO-HS, Nous Tous Gallery, and covered by Dezeen, Vogue Italia, Wallpaper*, Forbes, Art in America, Casa BRUTUS, and Art She Says. In 2020, Foundation invited her to be one of the first 24 artists to launch the platform. Previously, she has worked with the Guggenheim Bilbao, Fashion for Good, Whitewall Magazine, and Maison Kitsuné.

Designing With Games in Mind

Pearlyn Lii (she/her) started as a graphic designer and quickly built a body of work on various digital forms. In this conversation, we will explore the process of incorporating to gaming as a practice. We'll focus on learning new tools and looking for personal growth.

Lii draws inspiration from performance art and transmedia approaches. We will discuss the importance of starting with a story and understanding the desired outcome before selecting the appropriate tools. Similarly, you can effectively communicate with developers and engineers and ensure the realization of their vision.

Pearlyn will delve into the significance of pre-storyboarding and transitioning from graphic design to gaming for her new project. We will explore how Twitch can serve as valuable source material and discuss techniques to watch for while engaging with gaming streams.

From Online Girlfriends to IRL Intimacy

We’ll likewise work through her process of “Real Girlfriend” (2021), a performance-based exploration that takes place in augmented reality (AR). (Read more here on Foundation's site.) Through a series of videos, it offers a satirical critique of prevailing female archetypes, in contrast to what's been constructed through the lens of the male gaze. By amalgamating various women from the virtual canon, the project challenges and deconstructs these archetypes.

We will examine the role of avatars and their portrayal of eye contact in the context i.e. Uncanny Valley. Embracing imperfections and the desire for perfection, we will explore how eye contact can contribute to a deeper understanding and immersion within digital art pieces.

The talk will also touch upon the concept of intimacy in gaming and how platforms like Twitch allow for the expression of different personas and characters. By embodying diverse roles and considering their attire and behavior, creators can enhance their performance and engage with audiences uniquely and captivatingly.

Join us to discover how pivoting to gaming as a practice can unleash your creative potential, guide your tool selection process, and foster immersive storytelling experiences.

About Your Speaker

Pearlyn Lii is an interdisciplinary artist and streamer whose practice investigates personhood, neomythology, and the divine feminine. Her work narrates the plight of the human experience through fictional characters in alternate realities, reinterpreting harmful female archetypes. Drawing from mythology, science, fiction, and magical realism Lii responds to a personal and collective desire for a more regenerative, equitable future. Her work manifests through embodied performances, augmented reality, and video installations.

Lii is an alumna of NEW INC, a cohort of artists supported by The New Museum, and is a selectee of the Art+Code track in partnership with Rhizome. There, she founded nonstudio, an art and design practice that investigates mythologies through transmedia. Her work has been presented at New York Live Arts, New Art City, JO-HS, Nous Tous Gallery, and covered by Dezeen, Vogue Italia, Wallpaper*, Forbes, Art in America, Casa BRUTUS, and Art She Says. In 2020, Foundation invited her to be one of the first 24 artists to launch the platform. Previously, she has worked with the Guggenheim Bilbao, Fashion for Good, Whitewall Magazine, and Maison Kitsuné.

Our Approach

Game-Making Practice

It's for everyone! We believe that game design and thinking is not limited to "the video game industry." It's a creative point of view that any discipline can use.

LEARN FROM Doing

Our workshops are focused on activities with a majority of time spent on making things.

this is only the start

You'll grow from here. We hope that this is a stepping stone for you to permanently work with the material of games.