But Love has pitched his mansion in

The place of excrement.-W.B. Yeats

When Edmund McMillen, the design half of Team Meat, dropped Super Meat Boy in late 2010, he ushered in a renaissance of unforgiving and addictive platformers. For a larger gaming community he also helped define the character of Indie Developer. Super Meat Boy‘s unprecedented release, and the millions of copies sold since, solidified McMillen as a darling of the gaming world, ensuring a carte blanche going forward. And McMillen had big plans for his next project:

“It was going to be a little piece of shit.”

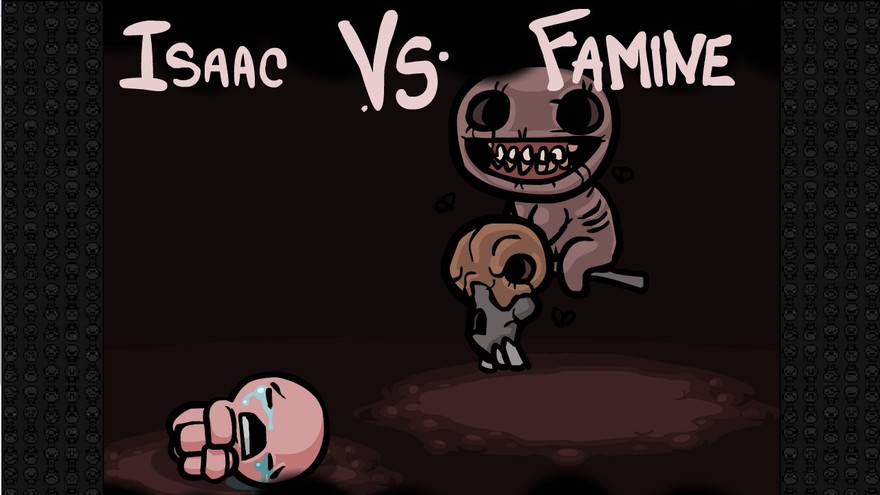

That little piece of shit would turn out to be The Binding of Isaac, a roguelike dungeon crawler in some diseased, festering vein of The Legend of Zelda, in which a fleshy, naked boy shoots tears at monsters and eventually kills his mother and crawls inside her womb.

On paper it sounds like a project dead on arrival; a creative mind in rejection of his own success, daring a new mainstream audience to go down into this pit with him and call it fun, call it art.

“I was fucking positive that Isaac would not do well,” says McMillen on a Skype call from his home in Santa Cruz, California. “In fact I was banking on it not doing well. I wanted to do something that was so opposite and unexpected coming off of Meat Boy.”

Only The Binding of Isaac did do well. Very well. It has sold over two million copies, spawned a major expansion, and two and a half years after its original release has retained a loyal and active following. Now McMillen is set to release an overhauled version for consoles under the tiltle The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth. In terms of longevity, Isaac has eclipsed its predecessor.

The story of Isaac‘s unexpected transformation into The Little Piece of Shit that Could starts, appropriately, with its design. People play the hell out of this game. Log in 300 hours and you can safely consider yourself a casual. Like a lot of roguelikes, its replayability is all about diversity. Tiered levels are randomly generated as Isaac starts in his basement and travels deeper and deeper in his own psyche, with a big, ugly smattering of enemies to combat and even more collectables for Isaac to use. The bullet hell of later bosses and permanent death increase the difficulty way past the rage quit; all that’s left to do is shake your head and laugh, to know you’ve been thoroughly beaten. There is peace in this defeat.

And then there are the collectables themselves. Isaac functions much like The Legend of Zelda in that you collect things along the way to build your character. Collectables alter projectile speed and strength, collectables can be used once and recharged, collectables offer passive affects, collectables can stack on other collectables for new (and sometimes glitchy) results. Pick up Guppy’s Paw and you can trade one heart container for three non-rechargeable Soul Hearts. The Common Cold adds a 25% chance of poisoning enemies. The Book of Revelations adds one Soul Heart and also guarantees the level boss will be a Horseman, who will in turn drop a Cube of Meat, which can be stacked on previously collected cubes of meat three times to create a wandering familiar called Meat Boy. There are nearly 200 of these items, most of which have to be unlocked by beating the game or completing in-game challenges.

“Randomly generated games are the arcade games of this generation,” says McMillen. “They are the future, what a perfect game can be: infinitely repayable.”

The sheer number of collectables, their sometimes ambiguous functions, and the random level generation were intended to build a sense of mystery, one that players would unravel over time, collaborating with one another as they made it deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole. All of this happened as McMillen had planned—only it happened immediately.

“I put in a joke screen of fat Isaac that appears if you beat Mom 99 times. I thought it would be impossible. I thought one person in the world would see it. That happened in the first couple of weeks.”

Replayability can only explain the game’s success to a point. But Isaac seemed to hit the afterburners where other roguelikes, like Spelunky, either settled into a niche audience or evaporated completely. Its popularity as a streaming game on Twitch is clearly a factor. But the real source of its longevity may be a step deeper: that is, Isaac‘s fully realized religious text.

Like the Old Testament story for which it’s named, Isaac‘s televangelist-loving mother (in place of Abraham) believes God has commanded her to make a sacrifice of her son. In the Bible, Isaac submits, but God stops a reluctant Abraham before he commits the deed. In the game, Mom is all about it, and it is implied (but never totally confirmed) that Isaac experiences a psychotic break and imagines himself escaping through a secret door in his room. The enemies look like mockups of prepubescent sexual angst and confusion. Isaac fights the seven deadly sins, often pisses himself, and, if you get far enough, ends up battling an angelic version of himself, and then some sort of dark mirror Isaac, a blue doll called ???, the totem in which Isaac likely stores all of his shame, grief, and fear. It is a sticky, feverish mess. Or, to put it another way, the nightmares of a child.

For McMillen, it’s personal. An anxious kid obsessed with death, he felt like a black sheep in a mostly religious family. Even though he went to Catechism for seven years, McMillen says he always felt the Bible, the fire and brimstone, were just stories. All of this went into the game.

“The Legend of Zelda is, on a personal level [Shigeru] Miyamoto exploring the unknown and having an adventure in his head. And I thought I’d put myself back where I was when I was little. I was just a nervous wreck. I had ulcers. I was a mess.”

“Isaac was me exploring that: if I were a kid again, if I did really believe in all the religious stuff, how fucked would I be?”

Randomly generated roguelikes may be the arcade games of this generation. But the most durable quality of The Binding of Isaac isn’t its replayability, the way it is for classic arcade games like Metal Slug or even Frogger. Its McMillen’s singularity of vision. Even if you don’t understand all the Biblical references, even if you refrain from looking up each collectible in the expansive Wikipedia, it is impossible to play Isaac and not feel yourself inside one person’s pungent imagination, to sense the deceptively thoughtful logic behind all the flesh and poop and tears. If Isaac compels us to spend hours on Steam the way we used to pour quarter after quarter into the machine, it’s not because the game is random. It’s because the game is purposeful.