Spend some time trying to figure out what people mean when they talk about “dadaism,” and you’re likely to run into the work of Raoul Hausmann. His work, particularly Mechanical Head and ABCD, brought photomontage to Berlin Dada, after all, which became the movement’s most well-known medium. In the Dadaists’ numerous photomontages and assemblages, bits and pieces of the world stuck together to transform into something new, almost tangible. But Dada wasn’t begun because a group of artists thought gluing magazine clippings together would be fun, or even aesthetically pleasing. It grew out of shock at the horrors of World War I and the rejection of logic and reasoning. Nothing these artist saw in the world made sense to them anymore, and so they embraced irrationality. Dada took nonsense and irrationality seriously.

The idea behind the form is to take a collection of other various works, and combine them to create a new whole without completely ripping off the source material. It moved out of the photomontages: William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch embraced a uniquely Dadaist non-linearity in format. It was a collection of fragments, and began what came to be known as his “Cut-Up” period, making use of a technique that was apparently created at a Dadaist rally, when Tristan Tzara decided to create a poem by pulling words out of a hat.

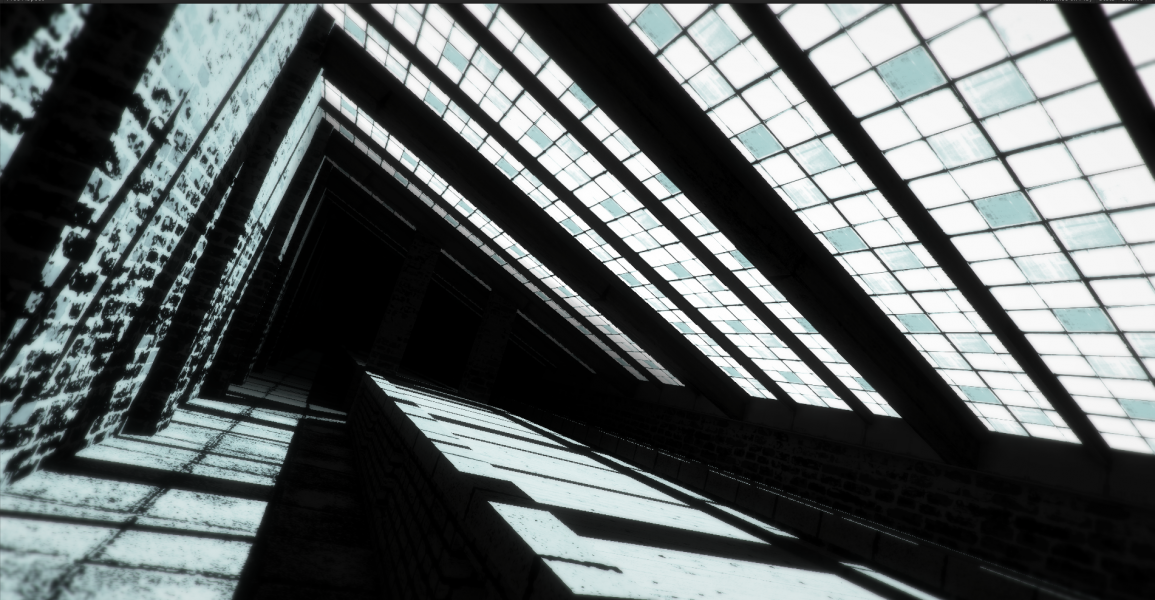

It’s this same combination of seemingly random elements into a cohesive whole that Alex Harvey has been working towards with Tangiers, a disorienting stealth game inspired by a myriad of complicated sources. Dada, Burroughs, Hausmann, Thief, and Dishonored are all present, as well as performance art groups Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire. There are references in everything. The shot of the apple-headed person you see in that dark trailer? It’s meant to reference Burroughs’ wife, who he drunkenly killed when trying the William Tell trick. The name of the game itself is an homage to the time Burroughs spent in Tangier, Morocco, and the work he produced there. The city of Tangier has its own history, entangled with international intrigue and mystery. Tangiers brings all of these semi-related threads together and ties them up in a neat, twisted knot of a game.

“I started out with a very literal adaptation of the Dada aesthetic, particularly with the photomontages,” Harvey said. “Everything taken from sampled or found sources, character’s faces being 2D photographs. Everything was fairly obvious, it wasn’t really subtle or mature enough.”

In other words, they were slapping the Dada directly onto the screen. There was no room for interpretation from the audience, no room for imagination. What you saw was what you got. But, like Harvey said, subtlety is the name of the game in Dada. Especially if that game is also stealth.

“So gradually pulling and pushing with other influences, we slowly built to the current look,” he said. “Putting the Dadaist elements into more of an undertone, bringing in some more filmic, noir influences to accompany the stealth mechanics.”

Burroughs, however, still prevails as the main inspiration. “The initial Burroughs influence on the narrative was by telling it in a number of vignettes within each level, little side-scenarios and overheard conversations. Disconnected set-ups that would often share recurring individuals or themes.”

Tangiers does not follow a set storyline. At the beginning, you get a simple title card, and that’s it. The story unwinds slowly as you make your way, out of order, through the levels. It’s something that Harvey drew from Lanark, Alasdair Gray’s realist/dystopian fantasy that is told in four “books” that are read out of order. And so in Tangiers, as in Lanark, you may know the ending before you know the beginning. But doesn’t knowing the climax of a tale only make you want to know the exposition and rising action that much more?

“Experiencing things in a different order gives them a completely different colour, you know?” he said. “You go to one level where the outcome for something was a really tragic failure. Then later visiting the previous chapter, where everyone is preparing for an inevitable failure, you’ve now got a really melancholy air of futility about these preparations.”

Harvey confessed that it’s very much a balancing act, rearranging the chapters. They provide the chapter number at the beginning of each level, just so the player knows where they stand in the story, but the rest is unknown. It provides a nice sense of unease, not knowing what you will be encountering next.

The pieces are mashed together to form the whole picture, but you have to guess at the true story by collecting odds and ends, like notes, audio recordings, and overheard chatter. Harvey claims you won’t find it all in one playthrough. It should shift around just as much as the world you inhabit does. Every action you take, he claims, will be reflected in the changing landscape; patiently waiting in the dark for the right moment to strike will earn you more shadows to hide in later, more chances to fool the night watch. Moving rapidly through the levels from ledge to ledge like some kind of possessed spider will open up the world for a little more chaos, allowing you to more freely do your thing.

We’ve seen a little bit of this before in games, but not on a level-shaping scale. Both the Mass Effect and Dragon Age series have delighted in forcing players to choose sides, and Telltale has tortured players into choosing between various evils in The Walking Dead. Characters have died by our hands; relationships have been shattered. But an entire world reshaping itself as you play is a departure from the traditional “violence begets violence” outcome.

And while the world pieces itself together according to some strange logic, so, too, will the player rearrange the very logic of language. Spoken words may simply fall to the ground, objects to be collected. Sentences become things you can pick up and store away for later use. Adding “I think he’s on the bridge” to your stash can be used later to frantically send guards—where else? To the bridge. Likewise, “I think he’s gone” will calm them down. And collected secrets from snatches of overheard conversations may open up a previously unknown and unavailable alleyway. Harvey told me much of this came about by accident.

“In early playtesting, we had little debug comments floating above the AI, describing the state they were in,” he said. “Somehow, I’d accidentally attached the properties of another object to them—they had physics behavior, falling to the floor—and could be collected! A bug that found its way to the core of the game’s design.”

It seems fitting for a game that addresses your actions and their influence on the ever-fluctuating changes of the world to include what began as a mistake in the finished project.

To look at each piece of Tangiers individually feels overwhelming, but it’s impossible to not be curious about them. When everything takes inspiration from something else, it’s hard not to want to know the story behind each one. But what of stepping back, and looking at the picture as a whole? The game comes to resemble one of those photos crafted by meticulously arranging other photos. The individual images are clear and evident up close, but move back and suddenly the larger picture appears in front of you. Tangiers looks to be just as compelling from either angle.