In 1943, psychologist Abraham Maslow created a system to figure out an age old question: what do people want? He called it his “Hierarchy of Needs” and it ranged from the basic physiological desires such as food and water at the bottom to the heady realm of self-actualization at the top. You’ve probably seen the chart. It looks a lot like the food pyramid.

Something similar happens in the realm of culture. For every consumer of media, there is a range of “needs” that occurs. We orient our free time in a similar way and for many folks, there is a competition for the top slot between movies and games and there are two men who have strong opinions on who should be at the peak.

– – –

At this year’s DICE Summit in Las Vegas, two titans in their respective fields held a candid one-on-one chat on the twin merits and difficulties of their respective mediums. Representing film was director J.J. Abrams, the newly-minted heir of the Star Wars franchise, and on the other side, was Valve CEO Gabe Newell, proprietor of one of the largest digital distribution platforms in the world, Steam. (Oh, Valve makes some games too.)

What transpired was 30 minutes of conjecture, argument, and the nature of story-telling. “We’re recapitulating a series of conversations,” Abrams said. These conversations, naturally, took place during sessions of Left 4 Dead. But what ultimately emerged was a recommendation between two mediums, one old and one new, about what they share and what they can steal.

While games clearly have the advantage of agency — you are in control — they suffer from a lack of pacing. In film, directors and screenwriters have control over how a story plays out. Every shot is composed and cinema guides viewers from one place to another. Abrams joked that players were “irresponsible” with story elements. Because game designers turn over so much to the player, they lose the ability to control their own story.

To illustrate, Abrams played a clip from Half-Life 2 where Gordon Freeman is supposed to be engaging in a deep conversation about how he survived and where he should go. Instead, the player spent most of the time teleporting books and throwing them at his conversants. Those type of distractions are natural to gamers, but are incongruous with what’s actually happening. Could you imagine how strange it would seem if Jason Bourne was continually opening boxes or staring out the window while having conversations? Games need to find new ways to control the pacing of stories while still staying true to their medium.

Abrams also suggested that games need to find new ways to hide their own machinery. Film is about “the illusion of free will.” In a movie like Cloverfield, Abrams wants the viewers to feel like they are actually fleeing a mysterious invader and never to be reminded that they are in the theatre. “Games are about exploration and experience, not moral inevitability.”

“We’re always trying to hide the machinery. You’re always leading them to critical moments. In a movie, you want the actions to be organic but it’s a magic trick. It’s a harder thing in games to get that experience, to hide that machinery when it’s not full of action.”

There are moments in games where you are reminded that you are in fact playing a game. Those design decisions can be as simple as making the UI more seamless, but the more that games can remove the scaffolding from visible view, the better.

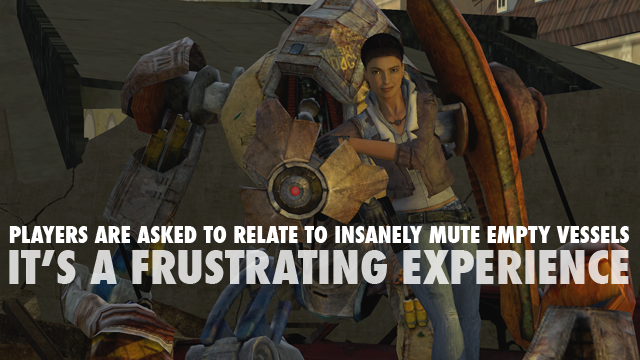

The holy grail for games is character. Throughout the history of the medium, protagonists have been silent — like Master Chief — or surreal. Abrams notes that’s a problem. The intent on the side of designers is to let the players dictate who someone like Master Chief is, but Abrams counters that result is something vastly different. It’s difficult to relate to characters who bear no resemblance to actual people in the real world. “Players are asked to relate to insanely mute empty vessels. It’s a frustrating experience.”

The key is letting players breathe and spend time developing who your character is before the main course commences. “Die Hard spends 23 minutes developing characters,” Abrams noted. “That’s a lot of time.”

The fear, of course, is that players lose interest, that they don’t want that type of development. We accept character development in film but less so in games. If things aren’t happening immediately, then we’re compelled to turn off the machine. Navid Khonsari, director of production at Rockstar on games like Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, once joked that a cinematics director’s biggest fear is “the X button.” Players will jump ahead if they’re not immediately compelled. That’s a problem with literacy and audience, not of form. If games fail to spend that time explaining their own narrative self-importance, players will continue to view characters as second-class citizens.

The good news is that cross-pollination is on the way. Abrams and Newell closed their talk with one of the most exciting new developments at the intersection of games and film. Half-Life and Portal are on the table as the two have been discussing how Bad Robot and Valve can work more closely.

“We need to do more,” Abrams said. “This is what happens when movie people and games people get together.”