This article is part of Film Week, Kill Screen’s week-long meditation on the intersection between film and videogames. Check out the other articles here. And, if you’re in NYC, grab tickets to our Film Fest at Two5Six on Friday, May 15th.

////

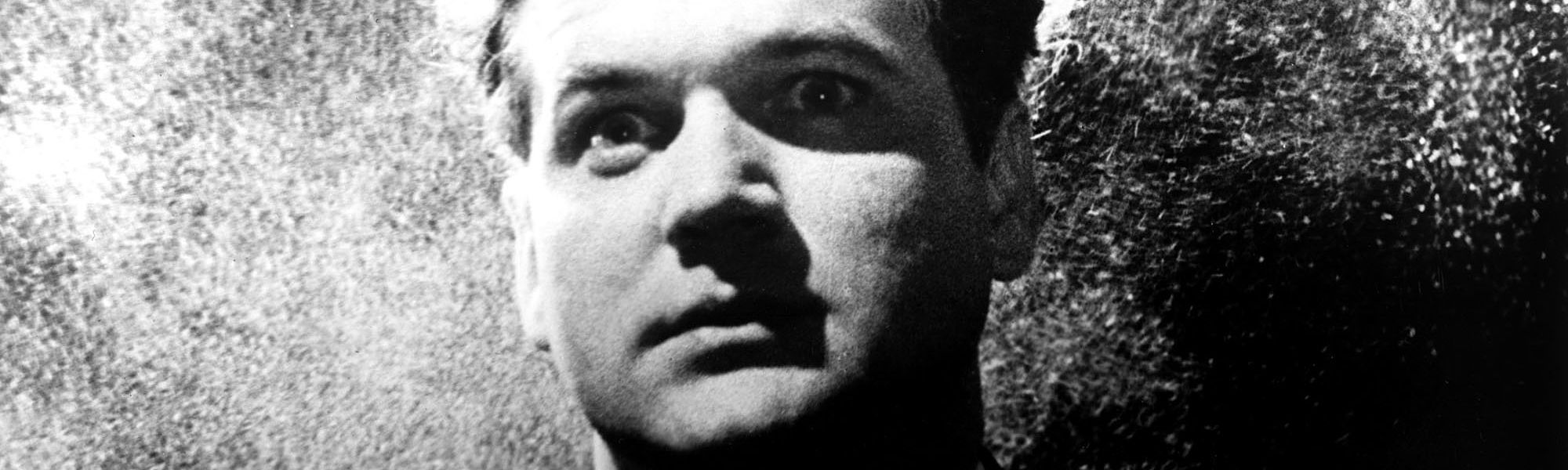

Fun fact: the screenplay for Eraserhead was only twenty-one pages long. That’s barely long enough for a short film. In fact, director David Lynch initially intended Eraserhead to clock in at a little over forty minutes, and his instructors at the AFI Conservatory didn’t think his screenplay would stretch even that far. Still, when the film was finished and released in 1977, it ran an hour and a half. And what an hour and a half. The film is just as light on dialogue and action as you’d expect from a project shot from twenty pages of screenplay, but Eraserhead is anything but sparse. Lynch packs each scene with densely layered industrial-ambient sound design, choreographs intricate background arrangements of flickering lights and shuttering machinery, and lingers for long, awful moments on the quiet unraveling of protagonist Henry Spencer’s life and sanity as he tries and fails to care for his deformed bird-like infant son. Lynch’s premiere feature is a bizarre high-contrast, black-and-white nightmare occupying the narrow margin between arthouse and grindhouse. And although Lynch’s style would evolve radically over the next three and a half decades, Eraserhead still operates as a sort of statement of purpose, hinting at the specifics of the director’s cinematic fingerprints.

Those fingerprints are distinct enough—and Lynch himself is successful enough—that even people who haven’t seen a single David Lynch film can guess what it means for a piece of media to be described as Lynchian. They might not be able to nail the subtle nuances of Lynch’s style, but they’ll guess broadly (and quite rightly) that they’re in for something weird. But Lynch’s surrealism isn’t just weirdness for weirdness’s sake. It’s the culmination of numerous tightly controlled authorial obsessions both technical and narrative.

Lynch’s creepy signatures—the droning anxiety-attack soundscapes; the painterly, almost baroque compositions of certain shots; the thematic preoccupations with bad dreams, uncomfortably fluid identities, sex as a means of both empowerment and disempowerment, and the metaphysical toxicity lurking beneath the surface of Rockwellian suburbia—are legion, and taken as a whole, they form the cohesive Lynchian aesthetic. The late David Foster Wallace defined that aesthetic as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” Think of Blue Velvet’s smiling detective John Williams who, when presented with a grisly piece of evidence discovered in a vacant lot, gently announces, “Yes. That’s a human ear, alright.” Think of a gut-shot Agent Cooper in Twin Peaks, staring up at an oblivious old man offering—not to call an ambulance—but to hang up Cooper’s uncradled phone for him. Think of Lost Highway’s Fred and Renee Madison discussing how much Fred dislikes Renee’s friends while driving home from a party at which Fred met a man who exists in two places at once. These juxtapositions of the aggressively bizarre and the aggressively mundane speak to the central truth of Lynch’s cinematic universe: lurking on the periphery of all the boring shit, there is a force at work that is metaphysically, psychologically, and existentially poisonous.

The cult of Lynch has had almost forty years to expand, so it was probably inevitable that his aesthetic would influence other artists. And of course, cinema has seen its fair share of Lynch devotees-turned-directors, churning out post-Mulholland Drive freak-outs. But Lynch’s shadow stretches well beyond the parameters of Hollywood, and the impact he has had on games has been surprisingly widespread and profound. There’s no shortage of designers happy to announce that influence through overt homage. Hideo Kojima included a direct reference to Eraserhead in his recent Silent Hills playable teaser by dropping Henry and Mary’s pathetic monster-baby in a bathroom sink. The televisions in Remedy Entertainment’s Max Payne broadcast episodes of Address Unknown, an in-game program featuring a backward-talking flamingo in a red-and-white striped room. And Deadly Premonition so closely resembles the first season of Twin Peaks that it often feels like a fever-dream remake, treading perilously close to the line between brilliant homage and actionable copyright infringement.

But when we talk about games as Lynchian works, we’re not just talking about winking allusions and rigid emulation. In order for games to be properly described as inheritors of Lynch’s aesthetic, they have to explore that intersection of the mundane and the macabre that Wallace identified. They have to mine the concept of personal identity and spotlight its fallacies like Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive. They have to peel back the top layer of reality and hint at the wrongness underneath. They need to get weird, but not just for weirdness’ sake.

Turns out, games are actually pretty good at exploring those themes. Hotline Miami’s incredibly intricate violence is not on its own Lynchian, but throw a silly animal mask on the assailant and juxtapose his rampages with his perfectly ordinary trips to rent videos or buy milk, and it suddenly says something about the ordinary and the grotesque, about the identities we choose for ourselves versus those we have forced upon us. Alan Wake, with its Northwestern small-town setting and episodic structure, may seem to be more apiece with the direct homages to Twin Peaks mentioned above. But the way it deals with memory and dualistic identity to ratchet up the tension suggests a purer expression of influence. Bully takes the traditionally squeaky-clean setting of a boarding school and gradually reveals Bullworth Academy’s toxicity by introducing combative drunken Santa Clauses, a homeless veteran (and possible alien abductee) living in an abandoned school bus, and more perversion and degradation than any fifteen-year-old should ever have to deal with. Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask repurposes character models from the franchise’s previous iteration, recontextualizing familiar high-fantasy archetypes in order to tell a story about the inevitability of death and disaster. And The Stanley Parable’s aggressively unremarkable office setting hides mannequin wives, walls of monitors, endless looping hallways, and a meta-museum dedicated to the development of the game, all in the service of a story about the artificiality of not just game narratives but real-world self-perception. These are by no means the only games that reflect Lynch’s horrific, boring, fractured, hilarious worldview. That aesthetic is widespread. A quick glance at Steam’s “surreal” user tag reveals five pages of games owing something to Lynch’s influence.

It’s important to note that, while the Lynchian aesthetic isn’t exclusive to games, its ubiquity in games is special. Films, television programs, and pop-music albums that call to mind Twin Peaks or Wild at Heart are comparatively rare. David Lynch’s films are esoteric enough to appeal to the same sort of specific enthusiasts likely to become game consumers and creators. But there’s more to it than that. Lynch’s works are themselves game-like, offering their audiences a set of tools and clues to piece together their central mysteries but withholding the solutions that would make their meanings clear. Mulholland Drive’s DVD release even included a literal list of ten hints (many of which were just as opaquely surreal as the film itself) printed in the insert to encourage fans to dig deeper into movie’s structure. The web-like intersections of Inland Empire has inspired its own sub-cult within Lynch fandom dedicated to figuring out what the fuck is going on in the film, complete with message-board arguments, amateur roadmaps, and magazine think-pieces that continue to be published nine years after the premiere. To be a David Lynch fan is to do more than watch the guy’s movies. Fans are archaeologists, excavating meaning and piecing it together both on their own and with other members of the Lynch cult. David Lynch makes participatory movies. It was probably inevitable that his work would be found and embraced by the gaming community.

////

This article is part of Film Week, Kill Screen’s week-long meditation on the intersection between film and videogames. Check out the other articles here. And, if you’re in NYC, grab tickets to our Film Fest at Two5Six on Friday, May 15th.