This article is part of PS1 Week, a full week celebrating the original PlayStation. To see the other articles, go here.

///

Aeris dies at the end of disc one of Final Fantasy VII. If you know what that means then you already know that it happens, and if you don’t know what it means then it doesn’t matter that you now know. There is a girl named Aeris, and she’s dead. She’s been dead, depending on your age, since you were quite young—since January 31, 1997, probably, the day the game was originally released in Japan. Aeris died, for all intents and purposes, on the very day she was born.

Aeris has run off like some goddamn fool when she dies, on a frankly insane mission to save the planet on her own. We chase her—we’re always chasing someone in Final Fantasy VII—through a weird dreamlike assortment of mollusks called the Forbidden City, then descending through the earth into a crystal cave, in which sits a tiny toy castle. The fuck is this place? You barely have time to process before the game decides: this is the place where Aeris dies. The game’s antagonist, a beautiful fine-fingered man named Sephiroth, glides his sword into Aeris’s chest. It floats through her. There is no blood and there is no sound and she falls soundlessly to the floor, her tragic purpose fulfilled.

(Did you know Aeris was going to die? You did if you played it sprawled out across various futons and car-seats over the past few weeks, during halftime of various basketball games and while waiting for various pots of water to come to a boil, lured in halfway out of boredom and halfway as a dare to yourself, some sort of weird goad, as if: Sure, you said to yourself, I’ll go back.)

This is all very sad for a lot of people, the sorts who feel sad about videogame characters dying. They talk about how they loved Aeris, how they had a connection to her, how they’ll never forget Sephiroth’s sword soaring through her perfect torso. I felt none of this, either time I watched her die. The first time I already knew she was going to; the game had been out for a year or so, and I think I’d seen the cutscene at my friend’s house anyway. The greatest connection I felt in that original playthrough was not to Aeris or Cloud or the third corner of our love triangle, a sportswear enthusiast named Tifa; it was to my golden chocobo, a majestic ostrich that I gallivanted across the globe atop and who cost me only a few dozen hours of meticulously researched effort. I loved that bird the way some people I knew at the time loved their neon-lit cars or listening to Nelly in those cars. I did not spend very much time in those cars, but when I did they seemed fun.

///

What I remember much clearer is the room in which I played Final Fantasy VII. This is easy to do, because it was electric blue: a corner bedroom, fit for a twin bed at best, that my parents had no real use for, and so painted garishly and filled with beanbag chairs and a Playstation. It was always hot, just swelteringly hot up there—this big old house that my parents couldn’t quite convince themselves to fully air-condition. The PlayStation room had a CD player hooked up to a boombox that spun anything I could possibly get my hands on, much of which was terrible skate-punk. But I yearned, like so many teens, for more. I pored over SPIN magazine in that electric-blue beanbag sanctuary, obsessing over albums I could buy the next time I had $15 and a ride to the mall. I scoured end-of-year lists, meticulously planning each eventual purchase.

And so I had OK Computer that year, right after it came out, and I spent enormous amounts of time listening to it while I—bored, hot, and angry—earned that golden chocobo. Both felt important to my sense of self. OK Computer was Radiohead’s third album—their most accomplished and complex yet, I explained to my tablemates in the lunchroom—an album about urban paranoia and suburban complacency. It had guitars, but they sounded like glaciers melting into an ocean. I listened to them and then stared at the built-in distortion pedal on my Peavey amp with dismay.

For a number of years afterward, OK Computer defined my taste in not just music but everything. Its snowy unease saddled alongside Final Fantasy VII’s pro-terrorist agenda, and so both locked into place for me during those months. As I became, increasingly, the sort of person who looked into things on the internet, I looked into finding more like them—shooting back and forth along the history of both mediums hunting for something, anything that might scratch the same itch, provide some clue to their origin. The same was true for Final Fantasy VII. Almost everything I played for the next few years was by the game’s creator, the Japanese monolith Squaresoft. Musically, I attempted to split the difference between Operation Ivy and Radiohead, and somehow ended up an emo kid.

///

Here’s how you play Final Fantasy VII, by the way: you hold the circle button. The good guys line up against the bad guys and everyone takes turns hitting each other. You wander through mountains and slums and rollercoasters, getting interrupted by enemies, and then you fight them by—holding the circle button. Each battle takes roughly a minute, and you will do it dozens of times over a couple hours of playing. The game punishes you for wrong turns: a long backtrack, full of these battles. Make too many wrong turns and you might die and have to reload an old save, a pound of flesh meted out in minutes. The game’s currency is not gil, the fantasy coin of its fiction; it is time, particularly yours.

The way games like Final Fantasy VII hook you is an understanding that your time is somehow valuable. There are, you always learn in such a game, numbers. They are churning like immaculate clockwork beneath everything, growing imperceptibly, as if counters of the hours you’ve invested. One of the things that remains beautiful about Final Fantasy VII in particular is how simple and almost physically understandable these numbers are. You put magic called materia in your weapons; the magic gets more powerful as you fight with it. Bars fill; numbers increase. The game’s great masterstroke is to build large portions of its plot around the acquisition and creation of this materia, too. A genre that thrives on byzantine plotlines and abstruse systems here locks them both into a single goal: get materia, and make it stronger. All the grand operatic plotting and high drama is ornamentation atop a single idea; if it were a building, it’d be one enormous room, sculpted out of numbers and paid for with time.

///

Over the years, emo has become the unlikely thing the good-looking kids listen to. On MTV, the bleached-blond Florida teens of my youth now have black hair, bangs, liprings; they wail about murdering their significant other or being murdered by their significant other; their band names are phrases and their song titles are full clauses. The almost post-war optimism of millennial pop music is now teen angst writ large, an opera with everything in the red. In direct contrast to this, the people who used to listen to emo have become embarrassed of it, but also more than a little protective. Our thumbholed Death Cab t-shirts are badges of geeky pride. We sneer at emo’s coagulation with goth and dubstep and scoff when screamo is called hardcore.

But there was a sort of inevitability to the mainstreaming of emo: the Get Up Kids and Saves the Day always sounded like popularity, or at least a reaction to it, the sound of skirting around the walls of a school-consuming romance, of existing in the shadows of one. It felt like what it felt like to not be popular. Skate-punk made a certain amount of sense given the general meteorology of my psychological state at the time, but emo felt like a lightning bolt straight into my bedroom. I could look up the tabs for “Karma Police,” but I could pick them out myself for a Weezer song. Emo was about getting drunk and high and hooking up and breaking up, all things I either enjoyed doing or presumed I would enjoy doing. It wasn’t a contrast to the frankly implausible quantity of time I spent role-playing as Cloud and the gang but a complement. The time I put into fantasy fueled the fantasies of the time—even, or perhaps especially, when I was bored.

///

Reload an earlier save. (The sword falls upward from her chest, the tears slurp themselves back into your eyes, and then:) Aeris is still alive. Me and her and the rest of the gang, at that point—a racist caricature, the sportswear enthusiast, a talking dog—descend some chain, and step foot out of the sprawling industrial wasteland in which the first portion of the game takes place.

We jog to a tiny village that could not be further from the one we’d left: some sort of Epcot ski resort, in which villagers might pop open the windows to sing to the birds. The town is literally called Kalm. Flutes pipe easily through the breeze. We hole up in a hotel room, and my party plies me for information about Sephiroth, who, up until that point, I’ve just clenched up with diarrhea-like rage at the mention of. And so I tell them a story about my hometown, from a time when I still worked alongside Sephiroth. And here the game does something very strange, something I did not remember it doing. It becomes textually denser without altering its surface, like a Haneke film. On-screen I’m controlling the protagonist from the memory, running through the town, but the details of the recollection keep filtering over top, changing what I can do and how I do it. I jog into the old town, past some soldiers, but—“Isn’t that, um?” someone says over top. The soldiers disappear. I’m back in the hotel, arguing, and then I’m back in my hometown. “You may visit your family and friends,” Sephiroth tells me. So I go take pictures, but every time the camera flashes, someone disappears.

“Have I come here before?” I ask, and it’s not clear if it’s the young me or the old one asking it. Did I ask it at the time? “I don’t remember,” one of me says.

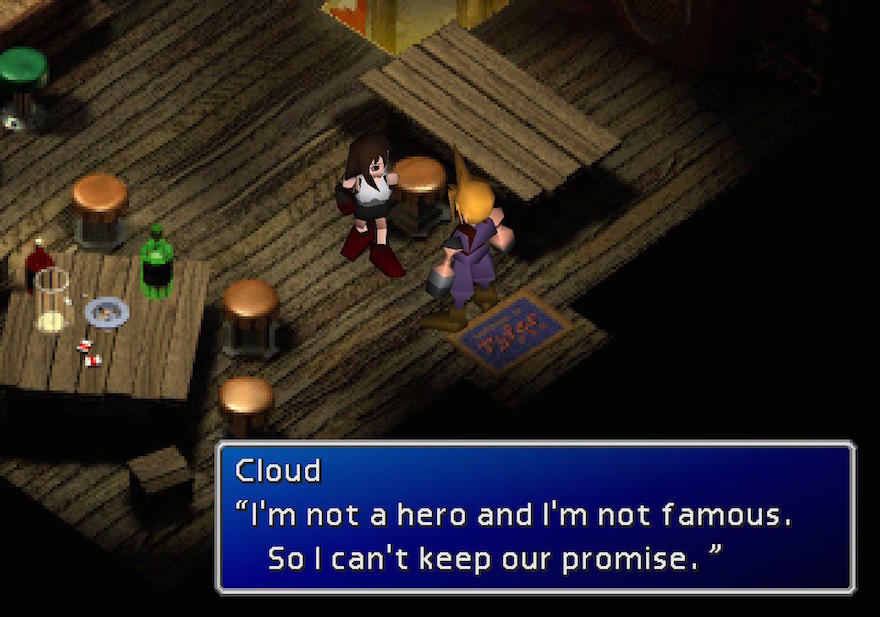

I walk into an old building. “This is … my house,” I say. “It has nothing to do with that incident five years ago.” But I keep poking around. I hear people from the present asking me to keep pressing on, and I can choose how the memory went—it flashes back even further, I’m a child now—then back to the present, then to that day with Sephiroth. “Did you go into my house?” Tifa asks me from the present. “Yeah…” I have the choice of saying, or, “No …” I can say. “Did you go into my room?” she asks. And I tell her yeah again, or no, depending on my whim. “Did you play my piano?” she says, and I answer. “Did you read it? My letter?” she asks. “You remember what it said?” she asks. “Do you remember all of it?” she asks.

“Yeah,” I tell her each time, or, “No.”

///

Eventually there were a bunch of us, banging around on acoustic guitars and broadcasting our self-loathing throughout the hallways of the high school. As we edged our way closer to those cases of beer and dimebags and accompanying makeout sessions we did so not under the rubric of rock and roll, as I had anticipated throughout my younger years, but of emo; it was all loathsome and hilarious and sad. But it was a sham, I guess like anything else in high school. We’d bare our hearts to each other and then use the findings to make up insulting new nicknames the next day. We resolved to live fast, die young, and make self-aggrandizing jokes about it as we went. (Eventually some of us did the second item on that list and the rest of us dutifully went through with the third, right after the goddamn funeral.) Some people went to college and others didn’t, or couldn’t. The lines remained drawn but they grew thinner, and eventually broke. There are now kids and mortgages, inevitably. I’m not sure if anybody ever listens to emo, but I kicked the habit about a year after I moved from the city. No sense standing still for art, and certainly not if it involves sitting around crying like a little kid.

///

The unfortunate part about replaying Final Fantasy VII is realizing that it is terrible. I mean, not terrible terrible, but it’s bad the way, say, a very old sci-fi movie is bad. It is enjoyable exclusively with mountains of qualifiers, with context and air-quotes and, preferably, your own reminiscences filling it in, making its absurdities lovable.

Its combat system, for example, is sublime, but bulbous and outdated, like a top-of-the-line laserdisc player. (Games like Xenoblade Chronicles and Persona 4, not to mention Final Fantasy 12 and 13, have alternately detonated and rebuilt the turn-based combat idea.) The game is sumptuously visual in places, like the ragged ghettos of Midgar or the low-poly euphoria of the Golden Saucer—but in most others traffics in underthought, generic scrims, looking like the child’s play-act it wants so desperately to be more than. Its story is told in leaps and vaults, all helicopter chases and propulsive forward motion—for the first ten hours, that is, and translated throughout with the quality of a fan anime today. It is loaded with casual racism, a jokey attitude (in one passage) toward sexual slavery, and its characters are, without exception, idiots. A friend of mine asked me recently, upon replaying it, who my favorite character was. After a minute of anguished reflection, I concluded, “Sephiroth looks cool?”

And it peaks early: you won’t even realize you’ve already passed its emotional centerpiece when you have, her corpse floating to the bottom of a sky-blue sea, but you’ve still got another 40 hours, kid. You are expected to keep playing in part to see what new graphical wonder awaits around the next corner, which is not a particularly good recipe for longevity. These lovingly created cutscenes have aged poorly, as you might imagine, but their scope remains impressive: a monster surging up out of the ocean, a spaceship soaring into a meteor in deep space, a main character being silently impaled while praying in a toy castle. If the fields full of combat and villages full of story form a gradually expanding cycle that composes the game’s runtime, then these videos are the carrot dangled before the player to keep her pedaling. Endure this cave, the game teases, and you might get to look at something cool.

This all felt amazing and essential at the time, but looking at it now, it seems superficial, and not a little mundane. Sort of like, well—adolescence itself.

///

Here’s the other thing about adolescence: we’re all essentially insane during it. In 2013, Jennifer Senior wrote an article for New York magazine called “Why We Never Leave High School” about the pervasive influence of those years on the rest of our lives. In it, she writes about how our prefrontal cortex is rapidly transforming during adolescence, giving us the ability to develop an identity. And so, she writes,

Any cultural stimuli we are exposed to during puberty can, therefore, make more of an impression, because we’re now perceiving them discerningly and metacognitively as things to sweep into our self-concepts or reject. (…) At the same time, the prefrontal cortex has not yet finished developing in adolescents. It’s still adding myelin, the fatty white substance that speeds up and improves neural connections, and until those connections are consolidated—which most researchers now believe is sometime in our mid-twenties—the more primitive, emotional parts of the brain (known collectively as the limbic system) have a more significant influence.

The gist is not just that many of our predilections and tastes of the time remain hardwired as we get older, but that we may actually be naturally predisposed to mawkishness in that phase. It’s not just growing up and finding new stuff that makes us embarrassed of emo—it is our very taste that changes, becomes less receptive to the bleeding heart.

And yet we still can’t stop feeling something when we revisit it. In fact, we may be chasing a very literal high when we do so. Our brains are flooded with dopamine during adolescence to a degree they’ll never again reach, and so when we listen to our old favorite bands, or play our old favorite games, we’re experiencing a pale shadow of those emotional peaks. Beneath a video soundtrack of Final Fantasy VII, one can see commenters ululating: “This reminds me of a time when I was a happy child,” goes the top comment. Below it: “i want to go back to 1997!!!” And: “This, somehow, brings tears to my eyes.” Also: “Is there a cure for nostalgia? It’s fucking paralysing.”

(Even people who have no real conscious desire to revisit the game may find themselves drawn back to it, as if destined to return to that great totem every so often, only to find it still engorged with flame, a couple decades later, and still worth slugging through for a couple of cold weeks, as if: Sure, they said to themselves, I’ll go back. Knowing the science behind such a journey, as well as its resulting malaise, does not make the predilection any less strange.)

///

Cloud, too, keeps going back to the well. He returns to his hometown a few more times in the game, each with diminishing results. During one of them, he stands in the flames of his childhood home and screams that nothing is real. The game’s writers are, at this point, starting to marshal their forces for a grand reveal later in the game; that, too, will involve a return trip home, but it takes place inside the inky black nowhere of Cloud’s mind. We play it not as Cloud but as Tifa, his childhood friend, determined to wake him from a coma.

And so we stand with a beleaguered Cloud on a floating rock in some aquamarine space. Pillars float eerily in the distance. A trio of paths spiral out into re-creations of their shared hometown, and they walk, first, to the city square. Together, real Tifa and mute Cloud watch a teenage Tifa, Sephiroth, and Cloud, flashing in and out of existence, as well as some other person, living Cloud’s earlier memories but with black hair now. Who is this intruder? “You must find the answer yourself,” Tifa tells Cloud, and us. Press the circle button. The second path takes them to what Tifa calls “that starry night at the well,” adding that “the heavens were filled with stars,” the camera then swooping below them and up to the night sky, as if to verify: stars. “Try to remember, Cloud,” she advises. “Did you imagine this sky? No, you remembered it,” she says, and so you press the circle button.

Finally a toddler Cloud appears and ushers us toward the final pathway. “It’s a very important memory,” Cloud manages to say. “Tender memories … a sealed up wish.” The camera swoops in on a window. We’re back in Tifa’s bedroom. Cloud’s not there, and she is surrounded by neighborhood boys. “Was that the first day you came into my room?” adult Tifa asks coma-Cloud. “Now that you mention it,” she says, “I don’t recall you ever being in my room.” The soup is getting pretty thick: there’s a child Tifa, a child Cloud, an adult Tifa, an adult Cloud, plus three random boys, and then:

“I used to think .. they were all stupid,” Cloud says. “I really wanted to play with everyone, but I wasn’t allowed in the group. Then later I began to think I was different. That I was different from those immature kids. That then … maybe …”

And a third Cloud, flickering in and out of existence, steps out of the adult Cloud. And there’s a fourth Cloud, enormous and superimposed over the entire tableau, on his knees, head in his hands, wracked with agony. “That was the first time I heard about Sephiroth. If I got strong like Sephiroth, I thought I might …” the Clouds say. Now adult Cloud, shadow Cloud, and enormous transparent Cloud stand back in the middle. But later beleaguered Cloud, transparent Cloud, and three flickering child Clouds will stand in the middle. The cross-chatter becomes unbearable. Cloud’s mind is pregnant with Clouds, all clambering over each other to get a peek into Tifa’s bedroom window; the game does not so much equate this fantasy with the end of the world as believe that they are literally, causally connected. A bored kid’s horny daydreams somehow dilate into a meteor hurtling toward the earth, and he must stop it with a sword the size of a tree trunk. It’s a universe in which lies aren’t paid for, they’re made real. Will you save the planet? Will you get the girl? Yeah, you tell it, pressing the circle button and submitting to its solipsism, its pop-emo fantasies … or no. The game itself would be the first to admit that the same thing can happen different ways—that your memory of it being one way is fundamentally, factually incorrect.

///

I drove back to that town for a night over the holidays to see some old friends and eat at my old Taco Bells, and I saw the old house, the one with the blue beanbag room. And you know what? Fucker looked enormous—bigger than I remembered. Some well-to-do young couple took it over and multiplied the whole thing by 1.3. It seemed engorged, with a wreath the size of a wind turbine hanging off one wall and lit up like God himself had festooned the house with Christmas cheer. A tiny rock outcropping had been erected leading into the driveway, which dipped before soaring back up into a brand-new veranda. Somewhere up there that electric-blue room had been painted over with a more tasteful taupe, its beanbags burned in a solemn ceremony, I presumed, just days after my family slammed the U-haul shut and hauled ass to Cleveland.

I drove past that bloated corpse of a home to some bar, where I saw people I know and people I once knew and drank so much that I could talk to all of them, and then so much that I couldn’t.

///

After the scene in Cloud’s mind everyone stands around in the meeting room of our airship. Cloud has come clean: he is a liar, he tells them, and a weakling. “I’m Cloud,” he says cheerily, “the master of my own illusionary world.” But he will still save the real world, he tells them. “It’s like you always told me, Barrett,” he says, before everyone yelps in unison, “There ain’t no gettin’ offa this train we on!” This is not a thing anyone has heard him say before, but don’t worry about it, you. The gang all laughs and laughs, together again at last, and they blast off together into the electric blue sky, children playing dress-up.