“Pick any color.”

This invitation isn’t as vacant as it implies. The “any” doesn’t reference the rainbow: You can’t choose the vermilion dunes of the Ivins mountains, or the baby blue waters that lap the shores of

It’s appropriate that a paper fortune teller acts as the background to the main menu in inSynch, its four triangles dividing each option. InSynch, too, alludes to great breadth, but this time in composing music with a cavalcade of instruments—from wooden flutes to brass trumpets—but settles on, instead, letting you “influence” the shape of a pre-existing bout of sublime acid jazz per the design of its software.

“Our stance when making the game is to try to strike a balance between proposition and freedom: a traditional instrument such as a violin offers no proposition but much freedom, whereas Guitar Hero offers no freedom at all but proposes you to act on it.”

As designer Oscar Barda reveals, inSynch is neither an instrument nor a rhythm game. It rides the uncharted middle ground between creation and mimicry. And, I’d add: For what purpose? Barder compares it to a droplet of ink in water, saying “you don’t control everything but that’s all right, you just play with it.” The same could be said of the paper fortune teller, but what makes that toy worthwhile is being able to trace each step towards the final outcome, your fortune. I don’t get that same sense of derivative exploration or serendipitous resolution with inSynch, despite that being half its goal.

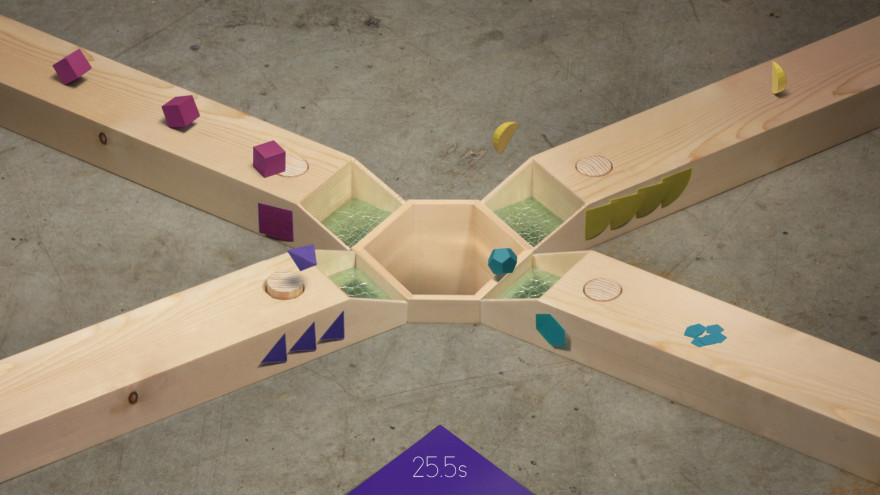

It’s a game played with four keys, each of which correspond to pop-up buttons at the inner edges of four wooden lanes. Spheres and pyramids dance down these lanes on account of the laborious stop-motion animation (worthy of a prize by itself). The destination of these lively shapes is the bottomless hole at the center of the crossway. Propelling them into it by using the buttons at the required time transforms them into notation; adding instrumental riffs and beats to the song. This would be satisfying, but instead it’s nebulous and frustrating due to the frequency at which the shapes arrive and the trickiness of getting the timing right.

It’s suggested that each shape corresponds to an instrument, but I don’t know which ones. There is no co-operation between the game and I. I’m pulling the lever of a slot machine hoping a song falls out fortuitously. It could be playful if my button presses matched my musical intent, or felt expressive. That would require my interactions be informed by knowledge gained through tangible feedback and experimentation, but there is none available at a readable level. And I refer to the casual “explore” mode here. The more challenging survival-based alternative seems to have no connections to its music at all, instead being a multi-tasking arcade game wedged into the same framework.

Straddling between instrument and rhythm game means inSynch has the appeal of neither. You can’t make your own music and you can’t perform it, which is a shame, because its papercraft is superb and the range of musical textures gratifying. Its design lacks coherence and lets it down, being as playful as a hundred dogs barking at you demanding to throw their ball, an overzealous cacophony.

You can purchase inSynch for $4.99 on its website.