This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

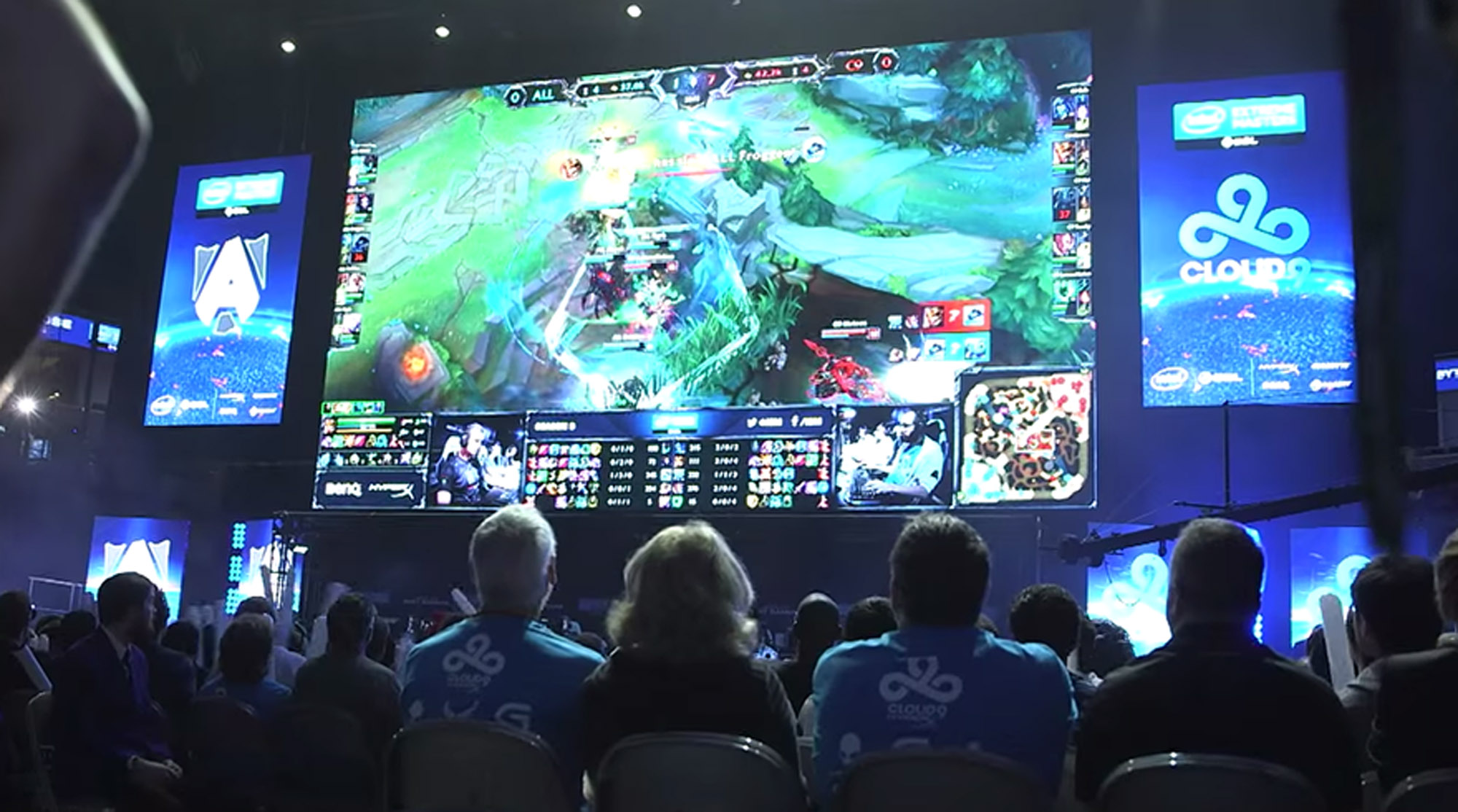

As seen in All Work All Play, the new documentary from Patrick Creadon, the current temperature of esports is sizzling. The tournaments are colossal, silicon-rich, stadium events, featuring the latest gaming rigs and highly competitive video games. But beneath all the electric festivities is a sneaking suspicion that no one knows what the future will bring.

“Esports are not going anywhere. They are only getting more popular. But the way they’re going to be consumed, and how they’re going to be played—that’s a different story,” said Michal Blicharz, the current czar of the Electronic Sports League, and a central figure in the documentary.

Unlike time-tested sports like golf, rowing, and baseball, esports are merely twenty years old, give or take a few. And because these are “electronic sports,” they are connected at the hip to the whims of technology. This means they could be dragged by the ethernet cable into unforeseen directions.

For comparison, while the sport of American football has made radical strides over its 100-plus-year history, it is still recognizable with two groups of players lining up on both sides of the ball. With esports on the other hand, it’s ridiculous to think that people will be playing the same turn-of-the-century computer games, or using old-timey equipment fifty years from now.

“There are those people—the typical magazine cover CEOs of gaming companies—that tell you, ‘the future is bright, da, da, da, da,’ but pardon my French, they’re all full of” baloney, he said, using an earthier term. “We don’t know. We don’t know because we don’t know where the medium is going to go.” He is in a good position to say so. He started out playing 1999’s Unreal Tournament in local internet cafes around Poland for $50 first-place prizes before helping shape the world of esports into a massive enterprise.

One gray area is the games themselves. With the exception of the rare game with the staying power of Counter-Strike, they typically don’t stick around for long. “That’s the thing about this versus traditional sports,” said George Woo, the event marketing manager who heads up the Intel Extreme Masters World Championship. “A basketball is a basketball, but esports are really dependent on the game title. I can’t tell you which game is going to be the game in the next five years.” As a consequence, players often hop around from game to game within a genre.

And yet this is only a slight adjustment when compared to a paradigm shift in technology itself. With the continued influx of smartphone devices, for example, and cool tech like virtual and augmented reality on the horizon, organizers are conscious that esports are heading towards a state of constant mutability. “We don’t know if the next major esports title will be in virtual reality, or if it’s still going to be a traditional PC game,” Blicharz explained. “We don’t even know what kind of controller it’s going to use. Is it going to be motion sensor-ing, tracking your eyeballs, or hand movements?” After all, one has to imagine that eventually the keyboard and mouse will become relics of a lost time.

Blicharz poses the thought experiment of a video game that is played in virtual reality. Currently the audience sees the same screen as the player during a match, but what if the player is wearing a virtual reality helmet to play the game? Does this mean that all the spectators in the audience as well as those of us watching at home need to put on virtual reality helmets too? “Probably not,” he said, “[But] we don’t know. None of us know. That’s what makes it fascinating.”