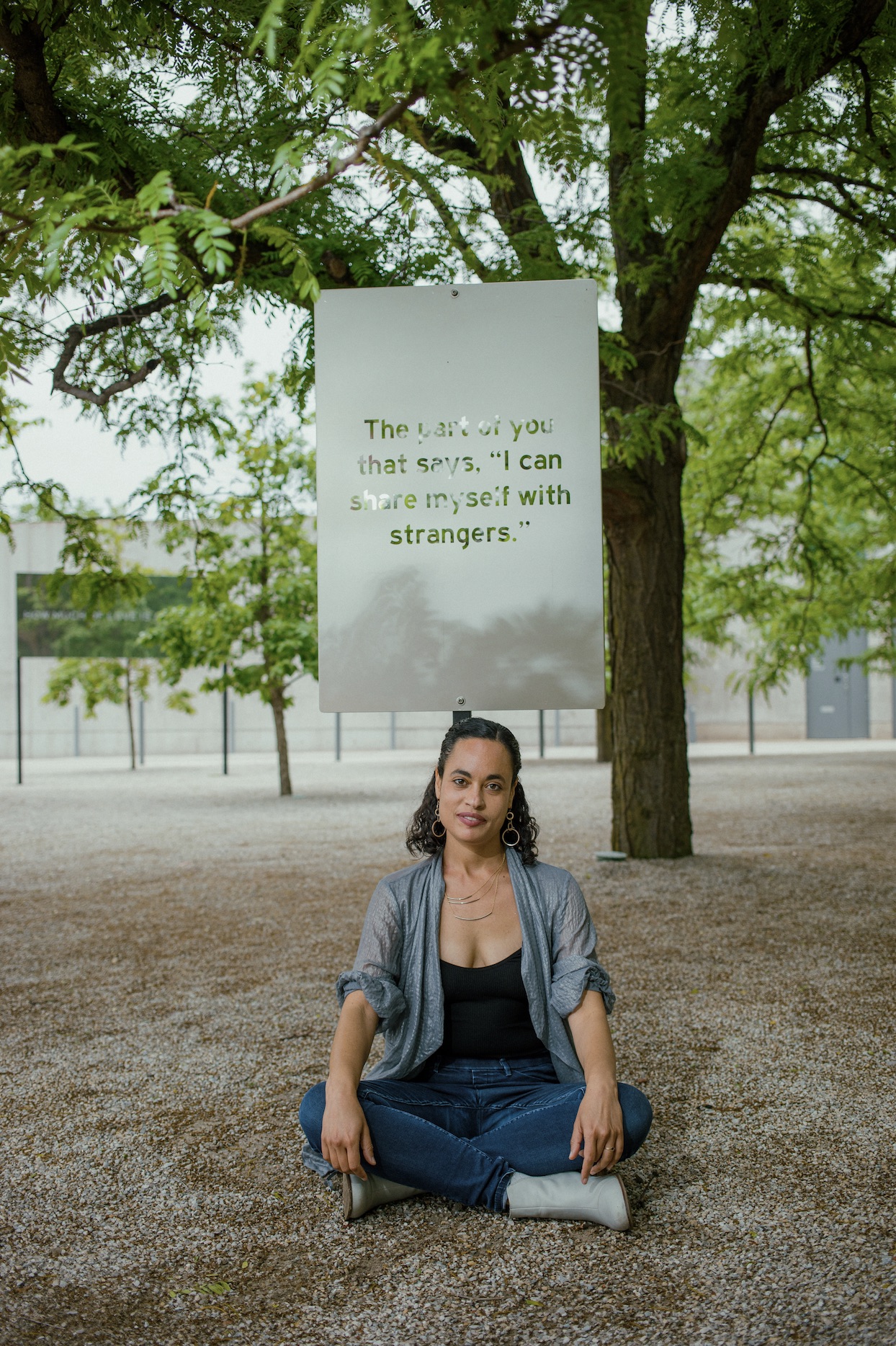

Multi-disciplinary artist Chloë Bass’ practice is a long-term investigation on what it means to interact with and form intimate connections with one another. “Wayfinding,” now on view at the Pulitzer Art Foundation, utilizes public signage to poetically interrogate our private relationships with public space through constructed sites of encounter. “The Book of Everyday Instruction,” an investigation of interaction in eight chapters, takes the form of both an exhibition and a physical book. Orbiting around various one-on-one relationships—whether an individual and an institution, or a body in space relative to another—the multi-pronged project celebrates and challenges togetherness.

We speak with Chloë about being the Ultimate New Yorker, her fluid conception of participation and play, and how not documenting preserves a moment’s authenticity.

Was there something about growing up in New York City that shaped your worldview and practice; that informed your experience about making art with a public in mind?

I’m so obviously very much a New Yorker, for better and for worse. I don’t think that that’s better than being anything else. I joke that I’m the Ultimate New Yorker because I’m a fourth-generation Jewish, New York-born-and-raised person on my dad’s side. But also, my mom is an immigrant from Trinidad, so I’m also a first-generation New Yorker. That is what New York is.

The city is driven by both of these things in equal measure. This always has been, and hopefully always will be, structural. There’s an inability to let go of the fact that other people might be in the exact same place as you, at the same time, but having a very different experience. Once you’re aware of that, you start to imagine what those experiences might be. That’s powerful for me, even though I don’t necessarily hold to the idea of empathy as a good way of understanding how to make political decisions or how to operate in the world. Understanding that other people’s experiences are not the same as yours is valuable when we start to think about things like law, safety, or any public outcome of politics.

I grew up in a very creative family. My mom is an artist and a poet. My dad is a psychoanalyst, philosopher, and translator. Both parents are writers and thinkers, and my mom is a maker as well. I grew up seeing a lot of art. My parents kept a journal for me when I was little. I would dictate my day and write down what I said. There is evidence that we went to FOOD, the Gordon Matta Clark restaurant project, when I was three. Now I’m like, “Wow, that art history… I was there!

When I was eight, my parents took me to a sculpture show at The Guggenheim of Rebecca Horn‘s work. She makes interactive sculptures, performance art, and body-related work. You wouldn’t think that a little kid would necessarily think, “Wow,” but I thought, “This is the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in my life. I want to stay here forever.” My interaction with the object-as-a-body and the body-as-an-object blew my tiny mind.

You studied theater and performance studies as an undergraduate. How did you make your way from that realm into the realm of social practice art?

If people had been talking more about social practice when I was in undergrad, I would have gravitated towards that. The educational institutions I attended supported me well in my interests and capacity to do research. In art departments, however, what people were talking about felt fairly rigid at the time. I was asked to think about things that are skills-based—perspective drawing, copying a painting, and [memorizing] standard Western art history. These are good things to know, but they didn’t interest me that much. I wanted to make projects more about direct engagement, about collaboration, about bodies.

I did an apprenticeship with The Royal Shakespeare Company. It doesn’t get more straight, standard-theater than that. I loved it—even when you’re working in those very normative capacities in the theater, there’s extensive engagement with other people. It’s not even necessarily the outcome, but the process of theater being made that I love.

How has your understanding of participation may have shifted in the years that you’ve been working in social practice and direct engagement?

I come to participation from many perspectives all at once. It’s worth braiding those together explicitly, because New York City is highly participatory. Whether you want it to be or not, it participates in you. You have to be very stealthy for that not to be the case.

There’s the form of participation in what it means to make an artwork together—or collaboration. There’s the participation that happens through education. There’s voting, lobbying, protesting—all of this I consider civic participation. There’s what it takes to maintain a public system of any kind as participation. For example, the MTA in New York is a mess. It’s even more of a mess when people don’t ride it. The library system is amazing, but it’s really difficult to access or maintain that amazingness without participation.

I’m invested in public-ness and the public. Public to me is what falls apart without participation. In my work thus far, my sense of participation has been more like, “What am I asking people to do?” or, “What am I subjecting people to?” I don’t know if going forward, that will be true. I feel very motivated to create conditions where participation is actively encouraged and tactically made present—where you can bring [something] to the work [as a participant].

I’m not telling [participants] exactly how to participate or how to feel. I don’t like maintaining power structures through secrecy. It’s not because I’m trying to implicitly maintain my own power; it’s more that I am leaving an open space—that you look more closely, [a project] is more rewarding or different. If you look more closely than that, it’s even more rewarding. It gets you to a place within yourself that I hope is non-coercive.

Your practice orbits around intimacy and private life through one-on-one interaction. In “Book of Everyday Instruction,” your chapters centered on one-on-one relationships, as well as preserving the authenticity of that experience, the ephemeral. Can you speak to your intention behind not documenting?

There have been different projects and products made out of those interactions. Still, there is no documentation or presentation of what happens between me and my participants in a formal setting. None of it is recorded or directly photographed. The chapter that did have descriptions of engagement was based on taking Polaroid notes, but never of their face. This was a way of marking our time together by taking instant photos.

Later, participants completed surveys, as did I. From those answers—which were really about how they felt during our interactions, and forms of engagement—I created non-documentary recollections of the exchanges we had in our moments together.

Book of Everyday Instruction has its own cataloging journey that is still only for me, if it exists. Documentation really does shift what my participants are willing to do or say—or how they feel and what I can do. Most of those interactions with people were scripted, but they didn’t know that. They weren’t privy to anyone else’s experience; they didn’t know that I was saying some of the exact same things in the same ways to everyone on purpose.

That’s also where theater can come into it, where that too can take on its own kind of naturalness over time. Once they feed their own content into that shell—the script that I have prepared for the engagement we’re going to have—I respond from there.

The exhibition and process of "Book of Everyday Instruction."

When you write a script, do you anticipate responses or behaviors from your participants or co-collaborators?

I don’t think we can ever honestly say that we leave things completely open. We’re guided by our biases, our lack of understanding, our gaps. The way that you ask a question impacts how you get the answer. [For Book of Everyday Instruction], I tried to be myself in a scripted way. I tried to also leave space for if I was giving the same thing to a wide variety of people, that could work for them.

The interactions I had went in different ways. In one chapter, I asked everyone the same six questions. Then there were other projects where people had no idea that their engagement was that mechanized at a certain level. That’s a form of participation too. You are not the artist of this experience, but what you put in as a participant of this experience shifts what it is, and what it becomes.

"Book of Everyday Instruction."

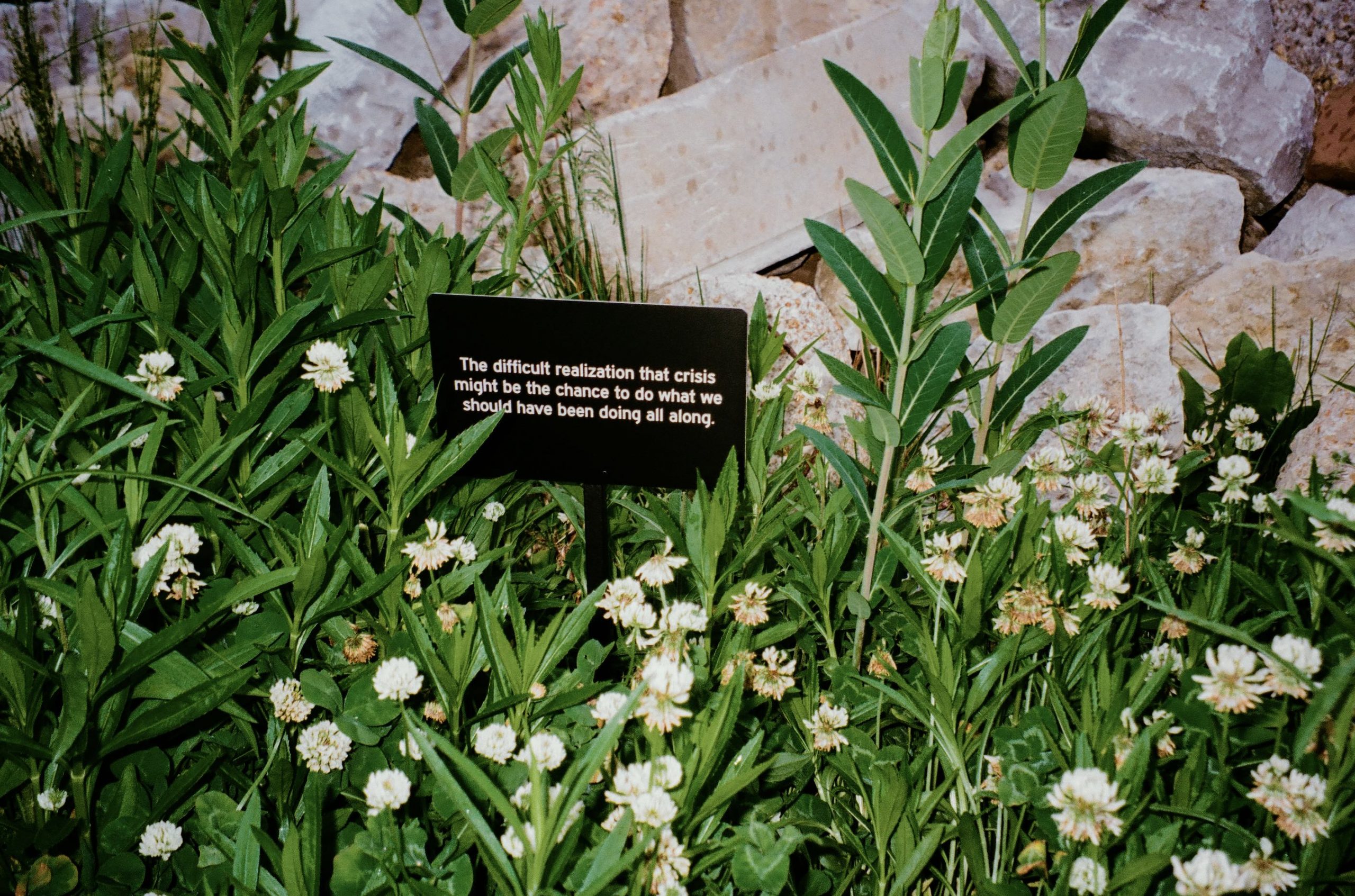

“Wayfinding” is a collection of pieces that centers on one’s private experience in a public space. How did you go about setting up these sites of encounters for people?

I talk about this set of sculptures as a choreography of objects. When you start to think of [a project] as bodies in space instead of an exhibition in a gallery, you make decisions differently. Because Wayfinding is so much about the encounter, it’s like encountering another body—but the body is the material, and the material has words or an image on it. That idea [then] brings you back to yourself.

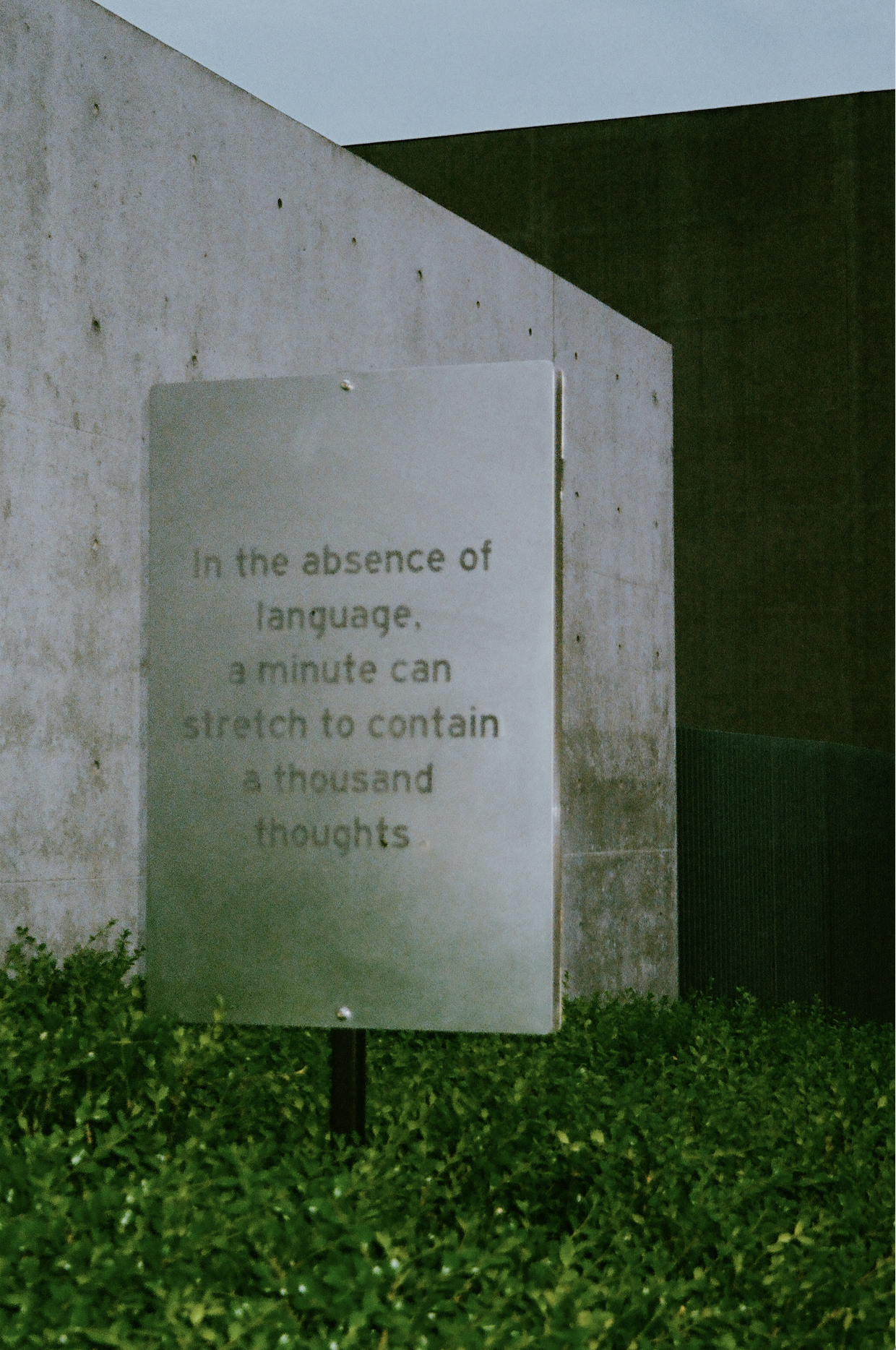

In the latest install of Wayfinding in St. Louis, were there specific decisions that were particularly exciting or memorable to you?

The thing about working specifically with the Pulitzer Art Foundation is that it’s a Tadao Ando building; it’s just beautiful. They trusted me hugely, but it was also a huge responsibility. At the same time, I was like, “I want to have one of these massive billboards right in front of the building,” but the whole time, I thought, “They’re going to say no, because their building’s perfect.”

I’ve never had so much infrastructure for me before as an artist. We had a huge crane, a huge van, and a heavy billboard base. But there was also this light feeling, because they maneuvered it into space so delicately, millimeters at a time with this machine in front of this perfect building. The whole time, I was just holding my breath, [hoping] that it would complement its environment.

That billboard reading How much of care is patience? wound up in front of the building. [I was thinking about] how it works with the architecture of the building and the neighborhood. It’s the lines of the environment, but it also reflects what is across the street, which is the other part of the project—an outdoor park site, where a lot of Wayfinding is installed. And how that brings that outdoor space, and the sky and the neighborhood behind it, which is someone’s house, a hospital, a parking lot, and non-picturesque back to that perfect minimal—fluid but impenetrable—building was special to me.

"Wayfinding."

You talk about thinking of these pieces as, or this piece as bodies, or the experience of encounters as bodies in space. Do you think of your work as narrative, or having a temporal quality to it?

Because I come from theater, time and bodies are the performance elements. That’s all it is. It’s like saying that flour and water is bread. I am always thinking about the temporal framework in my work. In Wayfinding, maybe some things are visible to people as they drive by. Maybe that’s the only way that they saw it.

Frameworks of intimacy are not always long-term. There can be very intimate things that can be very valuable that happen very quickly. [On the other side of that,] my grandparents were married for 72 years. There’s a lot of range there, but I don’t value one duration over another always. I don’t think it has to be that obvious to be interesting.

How has your work been an educator shaped the way that you think about your practice?

As an educator, I am disinclined to believe something that some artists do believe and say, which is the end thing is obvious or speaks for itself. I feel it’s my responsibility to both carry and unpack a lot of canonical cultural material, and to shift that canon as well. As an artist, I feel that’s my responsibility, but in a less didactic or narrativized way. If you’re not putting yourself in a position where that is possible for your work, maybe that’s okay for you—but I have a hard time letting that be okay.

"Wayfinding."

You regularly make playful experiments. What does play and playfulness mean to you and your body of work?

For these short-form experiments, it was all about leaving space for myself to operate clearly within a framework—which is this intimacy practice. Also, they exist to say, “Sometimes, I just want to do something else for two days. I don’t have to hide it or make it make sense. Here’s a space where I can do that.” That has been just important as a way of giving myself freedom, or leeway, because the system that I’ve set up is relatively exhausting.

I have a tendency to do exhausting things. That’s who I am as a person, but I’m trying to be a little bit more forgiving with myself. I have also been so schooled on what I don’t know about play in the last year because we have an almost five-year-old here. That’s my standpoint right now, after 14 months of pandemic-ing with a kid; I am not qualified to talk about play. As an adult, you think you know, but you don’t remember. I’ve never felt so much like an amateur [laughs].

What have you been all playing together?

It’s impossible to explain. For a while, we were playing a game called The Game. The Game is either going to last for four months, six months, or until he’s 16. We have been working on the narrative. The child plays two characters, and I am currently playing 17, or so characters. He’s very clear that we’re working on this together, and that I’m allowed to make suggestions about the direction in which it goes, but most of my suggestions are vetoed [laughs].

It’s a very long narrative, episodic, multi-character quest, which has had many kidnappings in it—most of which get resolved relatively quickly, because we don’t know where to go from there. We have lots of little plastic toys that are our characters, so they’re talking. Sometimes we get so tangled in the plot, we just have to back out, like there’s no solution. Come back for further episodes of The Game!

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity. Interview conducted in May, 2021. Photographed by Chris Bauer in St. Louis, Missouri.