When we look at our phone screens, we typically aren’t thinking about the borders. We don’t notice the edges of our phones and how those boundaries limit our experience. It’s no wonder Apple’s crowning achievement for the iPhone X was adding a teeeeny bit of space to the edge of the phone. But that little frame for designers is everything. Things you could do on a giant 4K screen in your living room, you simply can’t do on your mobile phone.

ustwo games knows these boundaries intimately. They are a mobile games design studio housed inside of a larger global digital product studio called ustwo. The design shop ustwo is based in London and was initially known for their client work for folks like Google, Ford, Samsung and more. So when they started ustwo games six years ago, there was already a lot of accrued internal knowledge about how to work with small screens.

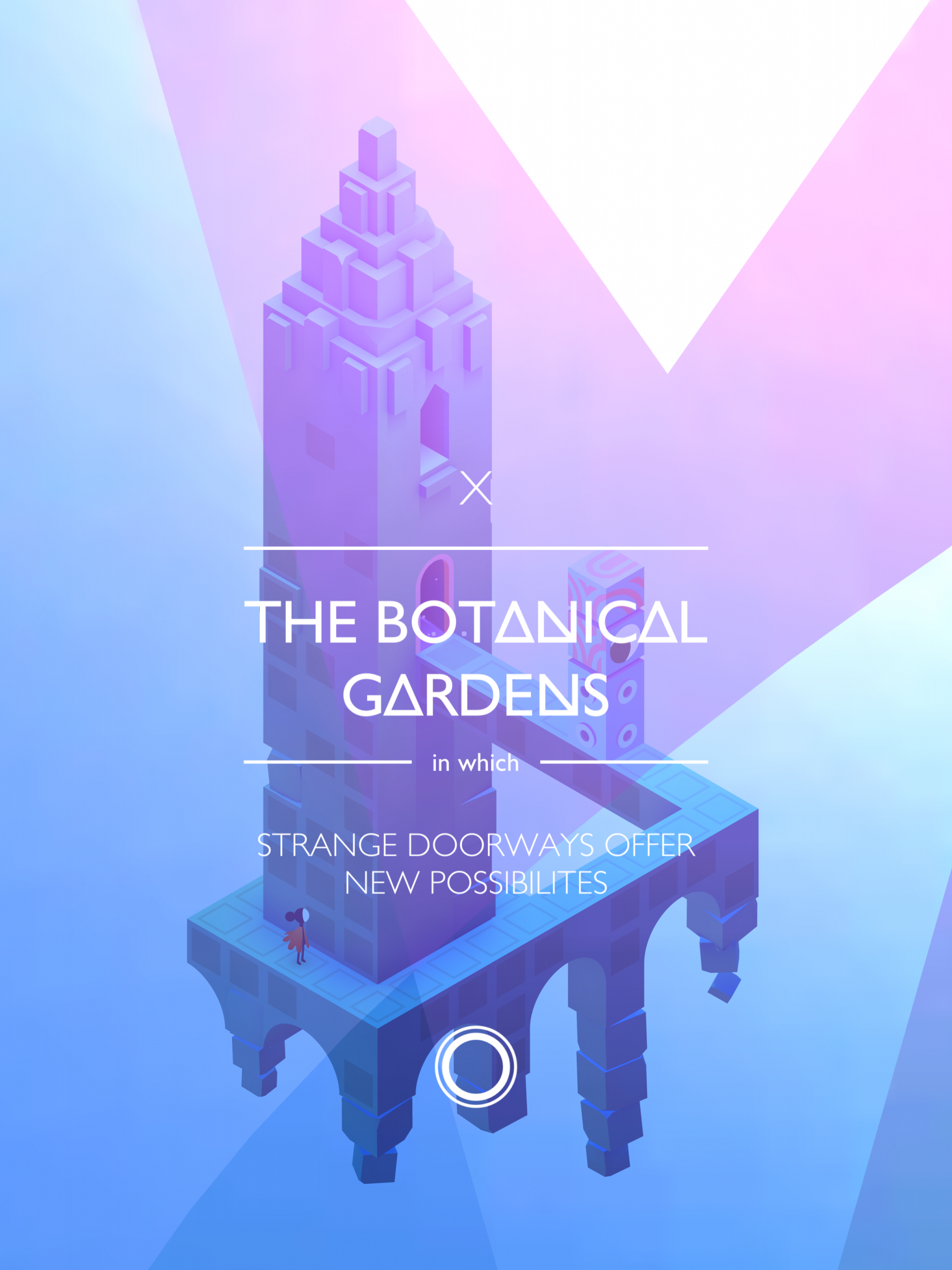

ustwo games’ Monument Valley was a smash hit for a few reasons. It’s delightfully colored. It uses space in a novel way. And most importantly, it’s simple! That’s not a pejorative. It’s very easy to understand almost immediately. In Monument Valley, you’re a silent princess on a quest for forgiveness. In Monument Valley 2, you play as a mother and daughter on an adventure together.

We spoke to Lea Schönfelder, a game designer on Monument Valley 2, about the differences between games and experiences, the difficulty of designing something easy, and how limits foster elegant design.

How did you end up at ustwo? Because I think the last time that we spoke, you were kind of doing your own thing.

I think when we last met I was working on Perfect Woman, which is a dancing game, an independent project and collaboration with Peter Lu, who is a programmer in Los Angeles. We released that independent project on Xbox One.

Then I saw that ustwo games were looking for new game designers, and I was really attracted to it because Monument Valley, their previous game, was a big success. I found it a really elegant approach to game design. It was almost something between an experience and a game.

For many gamers, the ustwo games titles are a bit too easy and almost not challenging enough, but it also enables a very large audience who usually doesn't play games to get to enjoy them and have fun with them. I can identify very much, myself, as I'm not a very big gamer, myself.

You use the word “experience.” What’s the distinction between games and experiences?

In classical game design, you learn about flow very early on. The flow diagram can be described as that game designer's try to match the skill of the player against the difficulty of the game. That means, in the beginning, people don't know how to play the game yet, so the game is fairly easy and the challenge not as big. The more the players play, the bigger the challenge gets so that they don't get bored. That is a classical game design principal.

Whereas in ustwo games, or a more alternative approach to game design, you don't talk about challenge much. I like to think of it more as a surprise or in two games we talk about these “wow” moments. That means if we test a level with our users, we obviously see how the difficult level works for them. Like, maybe if it's easy enough for everyone to understand and if there are enough visual hints and easy to understand screen design for them to get it.

But that's not all. The main point is if you see this little flickering in their eyes and if they see something new that excites them and they want to find out. I would say the main difference between an experience and a classical game is that an experience is about experiencing something playful or something exciting, something surprising rather than constantly just overcoming challenges.

"The main difference between an experience and a classical game is that an experience is about experiencing something playful or something exciting, something surprising rather than constantly just overcoming challenges."

It's interesting in other forms of interaction design like apps, there isn't as much a conversation around difficulty. Snapchat might be an interesting exception where there are a lot of features of Snapchat that are not readily apparent to people. The tutorial—it doesn't really exist. In some ways, there's a puzzle-like mentality around something like Snapchat, which you can talk about.

Generally speaking, when I download a non-game app, there may be a learning curve, but I don't get the sense that what is being given to me is something that is going to be confusing or that I’ll be frustrated by it. ustwo, by virtue of being a development studio, makes all kinds of experiences for a wide range of humans. Do you think that has anything to do with this particular perspective that you mentioned about creating experiences over games?

For ustwo, it's definitely true. The history of [ustwo games] is that it grew out of a bigger design studio, with people who would work in user experience a lot and work for clients who actually make apps that are not challenging but easy to understand and easy to interact with. That has been historically a big influence on their games. Those were the people that they tried out the first game with the most. So obviously they got a lot of input in there and we kind of inherited that.

While I was listening to you talking about this whole field, I was actually thinking, like, yeah, maybe it is about the design focus on apps that you have in many apps that you are actually thinking from the user perspective in the first place. That is a value that we hold very high at ustwo games as well.

Basically, everything we do, the first thing—it has to go through is a user test, even a very simple, white-box level. Whereas in classical game design, even many game designers have a more technical background and maybe a less artistic and a less user experience background. That could actually be something that's related to this difference.

That question of difficulty is kind of a funny one. Because when we look at other mediums, like, let's say a John Cage piece of music or abstract art, there's an unapproachableness that's highly valued. There’s the sense that you're gonna see something, or hear something, or do something and you're not going to “get it.” It does seem like some of that has bled over into games where difficulty is sometimes treated as a sign of excellence as opposed to an unthoughtfulness. I feel like there's a lot of difficulty for difficulty's sake. I play a lot of games that are hard, and they seem like this is just kind of just poorly designed.

It's also so much easier to design something difficult than to design something that is really easy to get. It's interesting that you say that, or that you draw this parallel between the fine arts and game design—one thing is arts and the other thing is a very technical background, but it's actually something that I experience.

When I was at art school, we definitely had this divide between the applied arts and the fine arts. A lot of fine arts museums, you walk through and you kind of sometimes get that notion that you are too stupid to understand. As applied designers, obviously, you would design much more with the audience in mind and for the audience, which then a fine artist would see as something like selling yourself out.

I don't want to say that this type of art that you don't understand is arrogant, because they don't care. When I walk through a museum and I don't understand something at first, it can still give you something. Like you can still see a big green block and you don't know what the artist meant with it, but for you, it's just a very beautiful object, and maybe it reminds you of some time last year or something like that. I think that something similar should be possible in games.

I think what you get with the difficult games is that there is not that openness, that you usually have a goal that you want to achieve and it's clearly something not good if you don't get there, but maybe it's something that we as players can also appreciate in a different way. We interact with something that we clearly don't do in the way that the designer meant it to do, but we still get some inspiration out of it or some new thoughts.

One of the things I find really interesting about Monument Valley is the use of the phone as kind of like a frame. In some ways, it’s a very old idea like if you look back at old arcade games. A lot of games were like Asteroids where everything that you had was kind of like on this space and then you kind of moved through that space. Developing side-scrolling—that came, actually, much later. Could you talk a little bit about designing for things that are meant to happen in this 16x9 box?

Yeah. I mean, the most obvious thing that everybody can think of is that it's a really small space. So you actually have to be really simple and really elegant to get everything that you want on that little screen. The next big challenge is that devices nowadays are so different. You have the various, the small iPhones and the big iPad Pros nowadays, and things will look and feel very different depending on where you play.

In Monument Valley, the original game and also this game, we followed the philosophy that every screen that we design should be something that in theory you could print out and hang on a wall as a piece of art. Myself, I understand it more as a piece of illustration because the artistic concept would be something that would go a bit further for me. So that was, if we're talking about visuals, one goal that we always had in mind. It was also challenging from a design perspective. In Monument Valley, the core mechanic is you guiding a person around a path, and when there is a connection, the character would go there. Then you have all of these optical illusions that remind you a bit of the M.C. Escher illustrations, like impossible geometry that's possible through an isometric perspective.

Obviously, I think the little screen even helped us to be more elegant in a design, because what's important to know is also that just obfuscating the correct option is not going to be elegant design. Like an elegant design how I would describe it, or how I tried to design levels for Monument Valley, is that you have a pleasant object, usually a piece of architecture, that the player wants to interact with, without even having a goal or knowing where they want to go. You have these grip knobs, or rotators, and buttons that you want to play around with and you want to understand the system of that toy that you're using at that very moment.

Yeah, it's such a unique challenge. Because I can see how that very quickly you might over-design for all possible outcomes. I don't know how much you watch The Simpsons, but there's a great episode where Homer is tasked with designing a car, and it's a great episode about design. It's so specific to what he wants out of a car, that it doesn't make sense for anyone else. So Homer is 100 percent, super happy with what's been created, but everyone else is, like, “This car literally makes no sense.”

I think there's probably also a difference in whether you design a product that has to be useful for someone. I think then you can listen much more to your users than if you want to provide entertainment. I think entertainment is only entertaining if it has a certain authorship or idea behind it and obviously, you can't ask your audience for that idea.

A movie director wouldn't ask their audience for how the story would go, but they have an idea and express that in their movie, and it's enjoyable because the audience doesn't know what will come. I think that there is a lot of that creative work that the designers have to do in games that they can't give over to the audience or to the user tests. But everything that is usability or basically just seeing what your plan is and if it is actually how the user experiences it, like basically making a plan and then testing that against your audience, seeing if the experience is the thing that you imagined it to be—I think that can and should be done in game development as well.

One of the things that you mentioned earlier was this idea that every scene is a painting, a kind of idea. I think when you're designing, you kind of want every moment to be something that could be captured and printed out and put on a wall. I was curious to what extent do you think of individual players as being artists in that respect, and if so how does that figure into your design process in terms of what they can and cannot create?

Yeah. Monument Valley is a very restricted game, so usually, the player's very guided. There is only one path or one correct solution to every puzzle. But we were talking about that as well and about giving the player more agency, and there is one feature that is implemented in the second game now, which achieves that, I think, which is the mandala drawings. At the end of every chapter, you get to draw a mandala with one of the characters, which is a guided form of drawing a beautiful flower-like shape in the sky.

So we were thinking, how can we give the player agency, but the visual outcome would still match the Monument Valley style? That's when we come out with this multi-mirroring of the mandala. That means that every line you draw is mirrored like five or six or even more times, which gives it that even shape in the end. I'm quite happy how that turned out. It was a free form drawing for everyone, so in theory, if you drew something really ugly or obscene or whatever, then something lovely would come out of it. I'm quite pleased with that. I didn't invent it myself. My colleagues did, but I think it is a nice thing that we added to the second game.

Interview conducted by Jamin Warren on September 1st, 2017. Edited and condensed for clarity.

Photography by Abiola Renee. Art direction by David McDowell.