This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

In 2011, curious creatures took over the music festival “Splendour in the Grass” in Woodfordia, Queensland. Jimmy McGilchrist designed “Curious Creatures” as an interactive exhibit for the public; silhouettes of strange animals were displayed on a large screen, as if fenced in on the other side. Attendees could approach and engage with them: Stick your hand out and the animal would dip its snout toward you; get too close and the large chicken-like thing might cackle and flutter away. By the end, the question of which creatures are meant to be the curious ones is up for debate.

Matt Ditton’s Melbourne-based game studio, Many Monkeys, developed the technology for McGilchrist’s project, which would go on to festivals in South Africa and Austin, Texas. Born in Brisbane, he worked in the games industry for over a decade on franchises such as Krome Studio’s Ty the Tasmanian Tiger and Pandemic’s Destroy All Humans! before moving south and starting up his own company.

“I came down [to Melbourne] specifically to try the one thing I hadn’t done,” Ditton tells me. “I’ve been an artist, a technical artist, a programmer and a producer… maybe I could just run a company. Maybe we could just get a bunch of people in the room together and make stuff.”

That room is located in what’s called The Arcade: A consortium of game developers working both independently and together on various projects. A growing number of PC, console, and mobile games are being brewed here, a former warehouse now home to dozens of offices working in synchronicity. Mighty Games’ first effort is called Shooty Skies; the mobile shoot-’em-up that came out last year, features geometric animal-pilots shooting down robots across an isometric landscape. Mighty Games works out of the same room as Many Monkeys; in fact, Shooty Skies is a combined effort between Ditton, Ben Britten, and Hipster Whale, the team behind Crossy Road and Pac-Man 256. I mention another game getting good buzz out of Australia, the PC and PS4 strategy game Armello by League of Geeks. “They work upstairs,” Ditton tells me.

“The Australian development scene works really well because we are so close-knit,” Ditton says. “Geographically we are incredibly isolated. It’s a long way to get anywhere. And we share so many resources because we’re the best resources that are easy to find.”

Such collaboration has risen out of a great trauma, Ditton shares. Not too long ago, there was almost no Australian development scene at all.

“In 2009, the world ended,” Ditton says, explaining how with the global economic crisis, large developers in Australia shut their doors in record numbers. There wasn’t the market for smaller, independent games as there is now; most developers worked as contractors on major projects for large publishers. When that went away, there was almost nothing left.

“In the space of nine months, every studio closes,” Ditton remembers. “What now?” Without a steady job, Ditton taught at the Griffith University in Queensland while working on side projects. In 2011, he finally moved south to Melbourne and decided to begin again, using his talents for interactive art installations before moving back into commercial development with his first independent mobile game, Breath of Light.

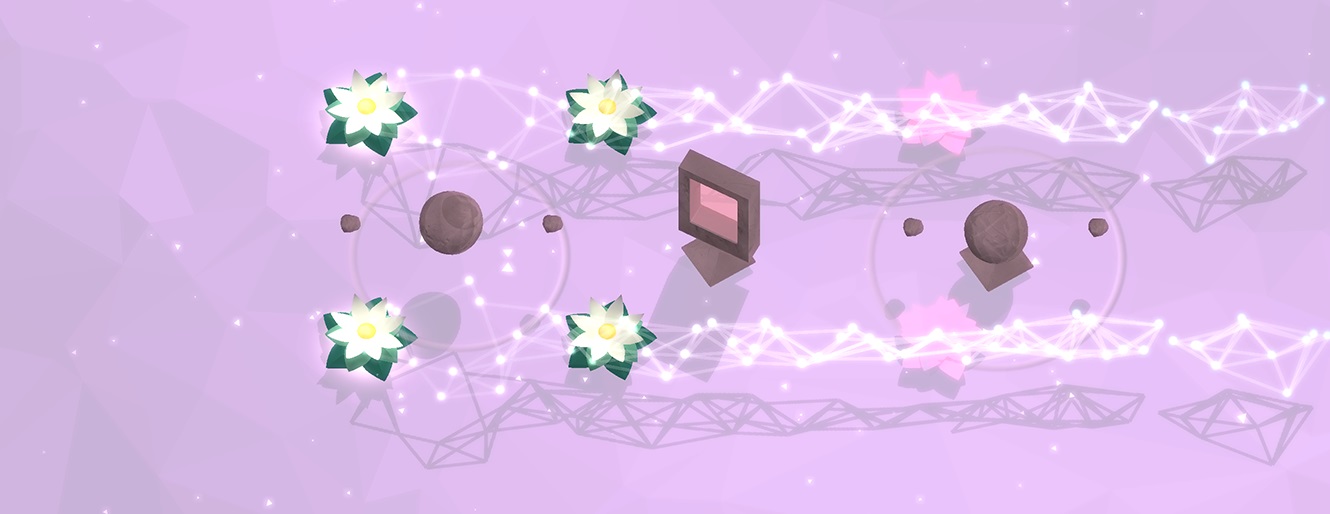

Light is a relaxing, Zen-like experience; you direct stones and rocks around a spare, colorful garden in order to shift a flowing energy over flowers waiting to bloom. It’s lovely and low-key; the pace and atmosphere demand headphones and a comfy chair.

But its original incarnation, titled Feng Shui Master, was more aggressive and combative, moving furniture around a house to perfect the titular aura. “It was an interesting game,” Ditton says of the first build, “but the joke was stupid.”

Australian game studios are anything but a joke these days, with success stories like Halfbrick’s Fruit Ninja and Jetpack Joyride coming out of Brisbane, while Loveshack’s Framed and Alexander Bruce’s Antichamber were both made in Ditton’s newfound home, Melbourne. Predictably, Ditton tells me that Joshua Boggs of Loveshack is a friend. He doesn’t say if they exchanged notes. But it wouldn’t be surprising.

“I feel incredibly thankful to be working in the games industry now,” Ditton says. “Right now is the best the Australian industry has ever been. It’s also probably the most difficult. Everything’s kind of hanging together. People are looking after each other. But at the same time it’s really stressful.” With more independence comes greater freedom, but greater risk. You can’t hide behind a giant corporation; as a smaller developer, your game is a direct extension of yourself. And your friends.

“You’re putting yourself out there on this world stage. And there’s no safety net; all we have is each other to make it all work.”