“Embodied” may be the best word to describe the projects of artist, researcher, and educator Salome Asega. She has created VR experiences that evoke the channeling of diasporic spirits, a Kinect lesson that reinstates a dance form’s history, and a roulette wheel that sends participants to lesser-known corners of a world-famous museum. Experiences that physically engage the body are clearly at the heart of the artist, researcher, and educator’s work. Trained in creative technology and social practice, Salome’s work also centers the communities she is part of. Based in Brooklyn’s Bed-Stuy neighborhood, she’s a director at POWRPLNT, a digital art ‘collaboratory’ in neighboring Bushwick, where she also leads creative workshops.

Salome told us about her hyper-real upbringing in Las Vegas, the trials of working within the uncharted territory of art and tech, and the power for participatory work to destabilize the long-held role of the artist.

How did you make your way into merging art with technology and participation?

The path to working in this hybrid way is totally winding. I went to NYU for undergrad, and wanted to have a public and socially-engaged practice. I was studying participatory methodology and interaction, long before I learned anything about tech. I graduated and did a bit of traveling, some community organizing projects with people locally and in other places, and was seeing all of this amazing work happening at the local level. I wanted to find a way to connect people on the ground.

That’s when I became more interested in technology and started to build websites on my own. I learned how to code and was so geeked by what I was learning. It’s so satisfying when you do things with some numbers, you hit ‘run,’ and things actually work. I pursued an MFA in design and technology, and that’s where the door was just busted open. I fell in love with physical computing and interaction design that incorporated emerging technology.

Participation is a lens that challenges where the artist is centered in their work. I didn’t want to be the artist that was helicoptered into a site and made something, dusted my hands off, and walked away. I wanted to understand deeper levels of engagement; to work with an audience to develop a story or a narrative that is specific to place. All of my projects unfold once they’re removed from the site they were made for. That’s because they were made with very particular people and places in mind. For me, participation is a de-centering of myself or self-awareness of where I sit in relation to my work and other people in place.

Growing up, I was mesmerized by artists like like Rick Lowe. What has happened with Project Row houses where a community came together, bought debilitated real estate in a neighborhood that was theirs. They wanted to redirect the narrative of their own neighborhood—the idea that your collective creativity can have infrastructural impact. There are things that this artist center does for the neighborhood that are I’m sure beyond anyone’s original dream when they first started. It’s a cornerstone of the neighborhood and of the city. That was the art that I want to make with people, things that have lasting effect.

How did you translate that participatory point of reference into the work that you started to build as a technologist?

I suddenly had all this exposure to goodies that I could tinker and play with. If I wanted to maintain this methodology for making, I knew I had to widen the aperture here and ensure that other folks had access to the same tool. The most obvious path for translation for me was to develop a workshop curriculum.

At the same time that I was learning how to code, how to wire, how to solder. I was taking notes and thinking about how to teach this. So the minute I would learn something in a class, I would package that up and be like, How do I do a workshop with this?

In workshops I’ve hosted, I’ve been thinking there’s an added layer of application—really thinking about the real world implications of the things we’re making. Being intentional and deliberate, too, with what we’re coding, how we’re coding—how we’re even naming variables!

Every piece was couched in, This can become something in a real world context, whereas when you’re in a lab, or a program, you can just mess around. The point is to break something apart, and learn the mechanics of it. I think of my workshops as, We have limited time together. Let’s really be intentional about what we do at this time, and imagine a new world.

For “Level Up: The Real Harlem Shake,” you used the Kinect. It is a great embodied piece of technology, one that can felt magical for a lot of people using it for the first time. Where did the inspiration for this project come from?

This project was made at a time artists were hacking Kinect and trying to figure out creative applications for this tool. There were tons of documentation online, and I wanted to be part of that work. I partnered with a curator and dancer Ali Rosa-Salas, and Lightfee founder Chrybaby Cozie to develop this game. It was through a residency at New Museum and a dance company called AUNTS.

We came together and started talking about the Harlem Shake. The group of dancers Chrybaby Cozie works with are from uptown, so the Harlem shake means a lot to them. They feel as if they’re the last keepers of the dance. We were talking about DJ Baauer who made the song that created the viral trend where people in their offices were just shaking wildly to this music. You’d have to go pages and pages into a YouTube search before you could find videos of the ‘real’ Harlem shake. We were talking about the erasure that viral trend had caused.

So we asked ourselves, What educational tool can we make to bring back and celebrate the original dance forms? We brought in a bunch of dancers and mapped their shoulder movements using Kinect. We took over the theater and basement space of the museum, and had people coming in and out all day dancing.

It was truly celebratory, and highlighted the stakeholders of this dance form in New York City. We aimed to give voice and movement and face and visibility to these people. The conversations around algorithmic bias have further developed—have been more nuanced, more rich.

You see projects like LaJuné McMillan’s Black Movement Library, where she uses motion capture to create a library of Black movement vocabulary. It’s exciting to see that in the four or five-year gap between our two projects just how much farther this conversation has gone. It’s really beautiful.

There are apocryphal stories about who invented the dance for the Harlem Shake—but I don’t think there’s a single person who started it, right?

We heard so many creation myths during this game’s development—one that went back as far as tracing it to traditional Ethiopian dancing. I’m Ethiopian, so I was ready to claim that history [laughs]!

P0SESSION was an ongoing research project, and you were looking to connect virtual reality with some of the West African and Caribbean spiritual systems. Were you looking at VR as a tool first, then thinking of a project to map onto it?

I had seen a series of sculptures of Yoruba practitioners in the process of spirit possession. These figures are so mesmerizing; they’re human beings that have a floating orb around them.

During spirit possession, the Orishas and deities mount practitioners through the head. When you see this process, you see practitioners getting ready to put something on their head.

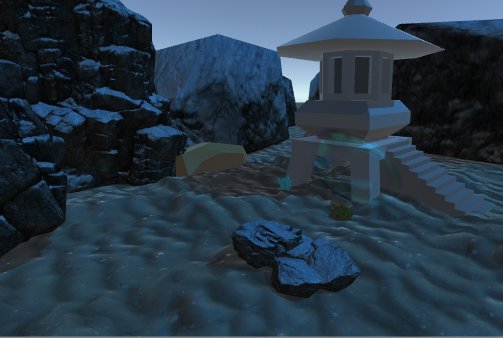

I was thinking about spirit possession as somewhat similar to the experience of putting on a VR headset, and being transported to a different world. I created these VR sketches where a person can enter a space and put on the headset, which takes them to a very specific Orisha’s world.

The first in the series is for Mami Wata, who is this deity spiritual figure who is just so regal. She lives in the water, and comes to shore. When she sees you, she promises you abundance, wealth and attractiveness, but you just have to follow her into the water. You’re worried when you see her because you’re attracted to these things that she promises you, but you actually don’t know if you’ll come back to land. You don’t know if her underwater palace, which has tons of riches and gold, is a trap.

She’s this femme fatale figure who is really strong and lavish. The Leo in me loves it [laughs]! I’m also named after another femme fatale figure, so I appreciate Mami Wata. She’s the center of the world for this first possession experience.

In both projects, there is a sense of body and movement connected technology as a conduit for this thing that people were already doing. Do you have a running backlog of other ideas where you’re like, I hope they create a piece of technology I can use to express this idea?

I should start sketching out the tech I need, but I think I’m just interested in unusual participation in a gallery or museum setting. There is a standard performance that we all do when we enter cultural or artist spaces. I want to break that—for people to know that they can be loud in a museum, to know that they can touch things in the museum, to know that museums are social.

On the development side, you’re using the Kinect and the Oculus Rift. What were some of the challenges using those particular technologies in a “non-authorized” way? Was there something that you faced that you could work your way out of—maybe left unresolved, or incorporated into the work itself?

The Kinect itself is so sensitive to light. It was fast-tracking and realizing, Okay, you’re making a work that you won’t be able to sit next to every day. Level Up is meant to be installed in a museum, and it’ll travel, so it will be subject to so many various kinds of lighting conditions. I appreciate that project so much because it made me smarter about code—it beefed up how I consider the logic behind a project.

With both projects, I had the hardest time figuring out how to package things so that they didn’t have to exist on any of my hardware—that other folks could easily access the game experiences I was making. With each of those projects, I hit a wall. I needed to bring my suitcase of things everywhere, for people to play or use. Everything felt really delicate, and it would be hard to swap out anything. It was very ‘homebrew.’ I’m not an expert coder—I’m very tech agnostic. All of my projects are about the story first, then figuring out the best tools to tell that story.

I also run into issues around trying to find the right sites for my work. Right now, I’m a Technology Fellow at the Ford Foundation. The exact challenge area that I’m exploring is that museums have a hard time exhibiting or presenting work like mine, because of an internal lack of capacity. There isn’t much knowledge about how to show extremely interactive works. It requires someone on staff to care for. It’s a capacity issue, and often you’ll see work like this presented as a public program or through the education department or something that is time-limited because it’s hard to maintain in a longer exhibition.

“There is a standard performance that we all do when we enter cultural spaces. I want to break that—for people to know that they can be loud in a museum, that they can touch things in the museum, that museums are social.”

Little Wheel Souvenirs, your showcase at MoMA, was inspired by your upbringing in Las Vegas. In some ways, this project is a break from some of your other more technologically-driven work. Here, you focus more on a raw, non-digital form of participation. What was it about casinos that seemed like a unique place for you to play?

I was born and raised in Las Vegas, and I was thinking about the roulette wheel. MoMA’s collection is wild and massive. There was something about chance that was really interesting to me. Being able to point your finger, all willy-nilly, and land on something really beautiful and great.

Casinos were my introduction to cultural artifacts. I grew up walking up and down the Strip. That was a huge part of my experience growing up because both of my parents, my extended family, worked in casinos—which, by the way, are more than just table games. There are malls in there, movie theaters, places for kids to hang out, roller coasters around the Statue of Liberty [laughs].

Before I was able to visit New York, I saw a reproduction of the Statue of Liberty. I saw the Venice canals at The Venetian, or the statue of David at Caesars Palace. I’ve now seen the original of these things—but growing up, I had an understanding of a hyper-real world. We didn’t have contemporary or modern art museums in Vegas when I was growing up. That was a way of understanding and making sense of a world.

I was in the inaugural cohort of artists with a social practice in the MoMA’s education residency, which had artists create interactive experiences that got audiences to explore the collection in deeper and more meaningful ways. I wanted to create that chanceful experience for audiences. I had a roulette wheel that corresponded to different works in the museum’s collection that were currently on view in the museum. Audiences could come and spin the wheel—which by the way, drove everyone wild. People were like, Oh, I can actually spin a roulette wheel and not have to put down any money. Great! I’ve always wanted it to do this [laughs!]

Being able to touch a roulette wheel is indeed a big deal.

That was the hook. Folks would land on a number, and it would send them on a goose chase around the museum, trying to find this work. They would come back to the gallery, where the roulette wheel is. There, they would win a souvenir or create their own souvenir based on the work they just saw.

How did you decide which pieces you’d highlight across all of the floors at MoMA?

I wanted to make sure folks hit all corners of the museum; places that they might quickly walk through, and have them take a moment there.

It was a combination of that kind of geographical mapping, and selfishly, personal interest. Works that really speak to me that I wanted to focus on—not work that was part of ‘MoMA’s Greatest Hits.’ We looked at Travelocity and TripAdvisor reviews of MoMA. So funny. People get upset when there are works of art that are really conceptual, and Starry Night isn’t on view. The thing that they know that is representative of MoMA—when you go to the shop, you see it printed on plates or key chains or magnets. We saw reviews of a David Hammons piece and people being confused and upset that it’s there. I was like, Okay, I want to send people to the David Hammons, and then come back and get a souvenir of it, or an Alma Thomas piece, or something like that.

I was interested in unpacking the cultural imagination of a place. MoMA shows up on any tourist map of Midtown. Before visiting, you have this image of what you think the place or what a New York art world will be like because you’ve seen the reproductions filter out… You’ve seen Starry Night on almost anything and everything. So you’re going to MoMA thinking, I’m going to see Starry Night. That was like the most interesting part of creating this experience is that I wasn’t sending people to Starry Night.

POWRPLNT is a digital arts lab that you run. What are you hoping to do with space, and what role do you see it play in the lives of creatives in Brooklyn?

POWRPLNT is what we call a digital art ‘collaboratory’ in Bushwick. It was started six years ago by my friend Anibal Luque and Angelina Dreem. Back then, it was a mobile digital art school that floated between tiny residencies and galleries in Brooklyn. It eventually found its way to the Red Bull Studios in Chelsea, through an exhibition that Ryder Ripps was doing. From there, we developed strong youth partnerships and found our way to the Hunter College gallery in Harlem.

It had an interesting trajectory—from very small gallery spaces, moving into more formal art spaces, and then landing in an academic institution. From there, I came in as a partner, and we set out to start a brick-and-mortar space. We found this bright orange beauty salon in Bushwick.

We began the work of renovating—shout out to Materials for the Arts, which was an amazing warehouse space in Queens where cultural institutions from around the city would donate unused material and other folks could scoop it up. That’s where we got the tiles for our space. The tables and more equipment, too. We did a modest $5,000 Kickstarter campaign to buy some used computers, did that successfully, and then set up shop as a community computer lab.

POWRPLNT functions as gallery space, internet lounge and an environment where people from all backgrounds may learn the skills necessary to express themselves creatively in today’s networks.

We had open hour time. Then in the evenings, we had sliding-scale and free workshops for young people taught by local artists and musicians. What PWRPLNT has been doing really well since our start is the open computer hours time and the artist-run workshops.

Now in the time of COVID-19, we’ve shut our doors like everyone else. But they’re slightly open because we have free resources available to the community, especially during the summer protests. We’re taking donations from people to give to protestors.

A lot of our programming, however, has had to shift. We have always been so place-based—so going virtual has allowed us to make thoughtful partnerships with mission-aligned organizations across the country. We recently brought together six or seven collectives and organizations to host a program—a weekend program called ‘Power Up’—where we taught six or seven workshops for young people worldwide. We’re a non-profit, so most of the funding comes from individual donors—people who really rock with us believe in us. Then some grants come from local foundations.

I’m hoping that doesn’t stop in a post-COVID world. I actually found it beautiful that we all came together to do this.

"Now in the time of COVID-19, we've shut our doors like everyone else. But they're slightly open because we have free resources available to the community."

How are you seeing a tie between the work that you’re doing at PWRPLNT and at the Ford Foundation, to bring us up to speed with the present?

I’ve been doing this work with PWRPLNT for a couple of years. I’ve been seeing how hard it is for groups like us to really find footing—groups that sit at the intersection of art, design, technology, social justice. Groups that are community-minded but just don’t have enough resources to do their work.

At Ford, I’m looking at groups like PWRPLNT, School for Poetic Computation, and Stephanie Dinkins’ AI.ASSEMBLY project. These groups are so community-rooted. There’s not enough cultural infrastructure to really support all of us. I’m thinking about what is needed to really care for this ecosystem of artists and technologists.

Maybe it means more grant opportunities specific to people who make in the ways that we make. Or more fellowships that help us distinguish us in our careers, that can really give us a platform for what we’re doing. Or more residency opportunities that cater to research and design, help us figure out new languages, and new ways of working. Also, making sure that we’re propping up people who are observing this field of practitioners. So really helping curators and critics to be able to talk about what is happening.

A lot of the work I’ve been doing at Ford thus far has just been exposure—getting arts funders or directors of various institutions to see the work themselves. It’s also been to build literacy, to really understand all the tools people are using and how artists come to use those tools in their practice. Also, what the costs are associated with that.

From there, actually interviewing artists or art and tech organization leaders to understand their needs. We ask, What is missing from your work? How can we help you? How can we show up for you and make sure that these two sides meet each other?

We’re in this moment with technology that feels really dark. So we need to prop up and platform artists working with technology.

Credits

Interview conducted in December 2020. Edited and condensed for clarity.