Like it or not, big data is bulging. And if the blowback over the N.S.A.’s access to the metadata of cell phone calls and Facebook profiles is any indication, all these digital stats and figures make a lot of people uneasy. And for sound reasons. Massive data collection efforts often don’t have public interest at heart, though the Obama administration would disagree. Frequently, it’s the candidates with the best algorithms that win elections. George Orwell couldn’t have scripted it any better.

But big data sure is convenient. Though its ulterior motives are often expedient, it opens up a world of possibilities. For every concern that’s raised about online privacy, we can instantly complain about it to our friends on the very social network that’s allegedly abusing it. In the field of gastronomy, a computational chef in Manhattan is data mining the unexplored frontiers of human taste buds, whipping up unlikely but apparently scrumptious combinations such as Czech pork-belly moussaka, and it’s all based on computer models of the palate. It stands to reason that videogames in some way could benefit from the exploits of raw data.

But how? Could data reshape our favorite games into an ideal form? Chethan Ramachadran thinks so.

The CEO of the San Francisco-based Playnomics, Ramachadran wants to unlock the world of information and reshape play. “The idea of what a game is is very flexible. [They’re merely] interactive experiences with some sort of quantifiable outcome and some notion of competition,” he tells me. In other words, pure possibility. All that’s needed to carve out new niches in play is a little help from a smart computer—one that can dissect our gaming habits and reassemble them in a more perfect way.

Ramachadran is cleancut and carries himself in the business-casual manner you’d expect from any startup founder in Silicon Valley. He stays positive, talks fast, and has a way of steering the conversation back to what he wants to talk about. When I was on the phone with him, that was social games.

His forte is the marketing of free-to-play games, compiling averages such as how long players from Turkey spend per session on strategic iPad games (46.3 minutes). But in coming months, his firm plans to roll out the next phase, enabling developers to apply statistical research to the creative workflow of designing games. Whenever you hear a tech guru with glazed eyes exalt the almighty virtues of the cloud, this is what they’re talking about: real-time data, pinging between you and the developer’s supercomputer, in a feedback loop that’s constantly being tweaked to your style of play. The impact could be radical.

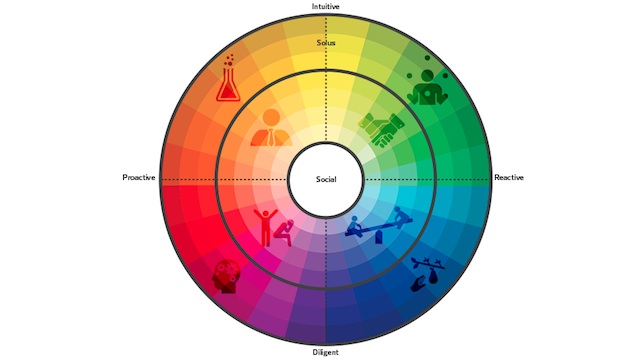

Here’s how Playnomics dissects how you jump, steal, climb, and dash. The data comes in and is given a score on a number of factors, from how long it takes a player to reach level 80, to how much they spend on enchanted Tartan kilts. (The company’s current strategy focuses on monetization, as Ramachandran freely admits that you can think of these scores as a credit report—an idea he may have plucked from his past career in investment banking.) The computer analyzes the patterns and divvies up players into groups, which he calls personality maps—brightly-hued pie charts that look like something you’d use when shopping for paint. From there, the crafty designer can incorporate this info into his project. “It’s a benchmarking playbook for how to build the game you want to build,” Ramachandran tells me.

Such psychological profiling might sound a bit off-putting. After all, if designers know exactly what people want, where’s the place for serendipity? We’ve seen the dark side of too much information before, such as when Disney became obsessed with audience research in the latter half of the last century. But unlike Walt’s infamous Audience Research Institute, which turned the art of animation into a color-by-number process and may have dampened the company’s creative mojo, Ramachandran believes his behavioral algorithms allow for nuanced delving. “The segmentation of the audience can be nearly infinite.” he says. “It can be behavioral, predictive, it can tie in the nitty-gritty game events, it can tie in to personality. It paints a really rich profile of how people play.”

It’s, of course, in his best interest to be optimistic, but Ramachandran seems convinced psychographics like his will lead to unprecedented dynamics in games. “I see a world of personalized games. And in that case, it’s a highly creative endeavor,” he says, explaining how the top-down approach allow publishers to hone in on undiscovered demographics. They could start with the ideal parameters for, say, people who like to explore vast environments and keep to themselves in games. From there, the experience could be specifically tweaked to, for instance, an adventure game set in northern New Mexico with assault weapons and Cormac McCarthy-style drug trades. It sounds awesome, in theory anyway.

The way Ramachandran sees it, the sudden surge of big data isn’t the death knell for artistic expression: real-time stat tracking can coexist with creativity. If we’re lucky, the statistical residue of things like achievements and gamification could change the way people play for the better. But there is also the danger that an obsession with data could wilt the imagination in games, as the Spy Party designer Chris Hecker warned a few years ago in his blog post on metrics fetishism. As analytics march onward, it’s important to keep in mind his conclusion.

“The metrics are the craft, and the intuition is the art,” he wrote. Let’s hope numbers don’t swallow us all.

Glare image via Terry Dennis.