A 20-something girl stands in an elevator. There’s an eye patch on her face, a shotgun on her back, and a pistol in her right hand. The door opens, and she hits the ground running into a room full of drones. They hover over her, firing red lasers completely bent on killing her. After all, why wouldn’t they be? Molly Pop is the head of the Zero Sum Gang, and she’s on a mission to topple the Fero corporation by raiding their bunkers one-by-one. She wastes no time, shooting down the flying robots in seconds, then travelling down a hallway into a large room filled with yet more AIs.

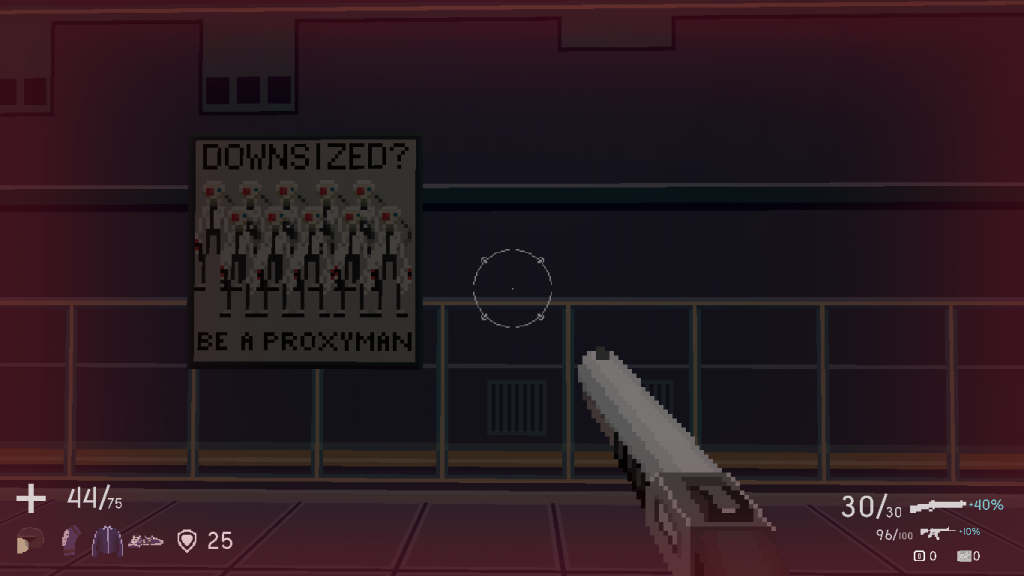

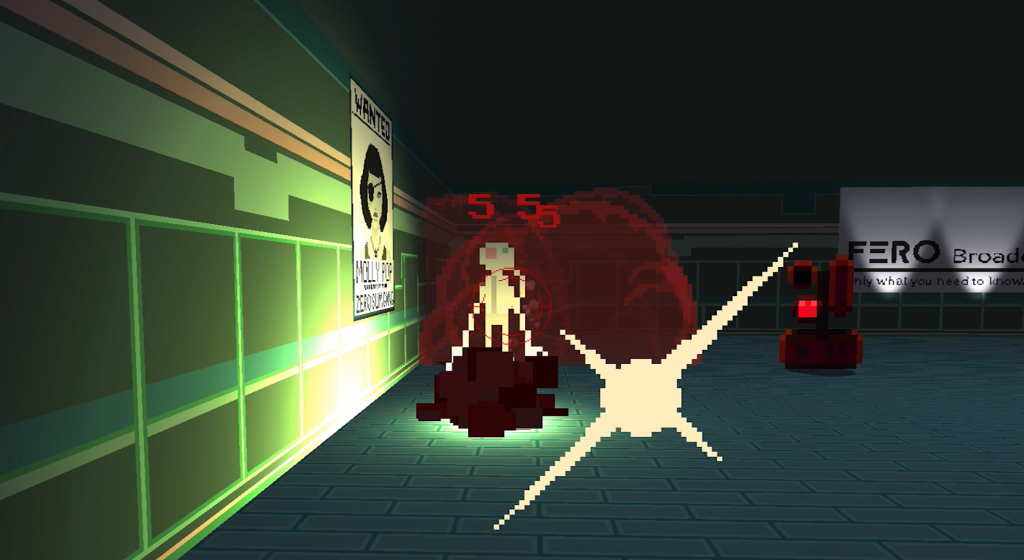

There’s something different here, though. A humanoid figure stares at Molly, firing a gun in his hand. Molly runs up close and unloads her pistol at point-blank range into his face. Blood sprays onto the floor and walls as a poster becomes coated with the man’s viscera. “Downsized?” it asks. “Become a proxyman.” A line of the same humanoid enemies rests in the center of the portrait, ready for duty.

Molly Pop pushes past the ad and heads to the exit elevator. She brags to herself about her successful raid, as she leaves behind dozens of dead proxymen and broken machines in pursuit of her true enemy: Fero’s corporate leaders.

///

Bunker Punks isn’t a standard first-person shooter. Created by industry veteran Shane Neville under the guise Ninja Robot Dinosaur Entertainment, Bunker Punks is about everyday heroes fighting against a wealthy megacorporation at the center of a dystopian society. Players take control of a group of post-apocalyptic freedom fighters bent on destroying the Fero megacorporation by raiding their bunkers, and claiming the loot inside for their own use. Play is split into two segments: building up the gang’s base of operations, and raiding bunkers for resources. Levels are procedurally generated and permadeath is active—meaning no two bunkers are the same, and players cannot load from a past save point if things go awry.

As a roguelike shooter, Bunker Punks is pretty heavily invested in its own lineage. Critics have called the game a throwback to DOOM (1993), hailing its fast-paced combat and engaging gunplay. However, Neville hasn’t neglected the underlying politics behind Bunker Punks. Fero advertisements litter the bunkers’ walls, encouraging profit consumption when money is in excess. Security cameras force employees to be on their best behavior, and bulletins implore laid off workers to join the cyborg proxymen army. The Fero corporation isn’t just a dystopian villain, Bunker Punks suggests—it represents the very worst of late capitalism. In other words, Bunker Punks’s post-apocalyptic world is self-aware of the present. Neville says this is no accident.

“Today, the largest corporations have more money than many countries, and there are private military contractors larger than some armies,” he explained to me. “If the government collapses, it almost seems silly to think that the wealthiest and most powerful people and companies in the world wouldn’t step up and at least provide for themselves.”

In a world where major corporations are given more power daily by the United States government, and federal spending diverts millions upon millions of dollars towards private military contractors in Afghanistan, Neville’s setting is incredibly relevant. In fact, Bunker Punks was written with American geopolitical and socioeconomic fears in mind. The more time Neville spent following current events on social media, he explained, the more he began to think about the ramifications of a global apocalypse in the United States.

“I thought that the world’s wealthiest people would have some sort of emergency plan in place, a place to go and live out the apocalypse in comfort,” he explained. Such is the case in Bunker Punks, where Fero reigns supreme, and its workers are left scrambling for scraps.

///

Humans are hard-wired to learn about the world through experience. Gradual exposure makes us familiar with our surroundings over time. We pick up small threads to hang onto—a certain hallway, a specific food, a special memory—and start to build a relationship with the locations we’ve visited. As we put these thoughts together, we eventually establish a narrative about our experiences. We begin to understand where we’ve been through stories.

In the same way, Neville doesn’t expect the player to understand Bunker Punks’s lore immediately. Rather, players are gradually exposed to the in-game world through hints and clues. Quotations from Molly Pop are placed across loading screens. Caravan merchants make small talk with the player after death. Corporate advertisements reveal how Fero is exploiting its workers. The player learns about the world piecemeal, putting together the full picture as they continue to experience life inside the Zero Sum Gang.

“The storytelling in Bunker Punks is very passive,” Neville explained. “I did this because I want the players to learn about the world bit by bit, as they play. It leaves a lot of questions unanswered and lets the player dig deeper.”

Neville’s approach to narrative design is becoming an increasingly common one in videogames. From The Binding of Isaac’s (2011) item pickups, to BioShock Infinite’s (2013) Vox Populi, action videogames traditionally encourage players to learn about the world as they go along. Questions about motive or origin may be left open, but that’s perfectly fine. As Neville points out, part of environmental storytelling is encouraging the player to fill in the blanks. In fact, this seems to be a staple of the roguelike genre.

“In roguelikes, each game tells its own unique story. The characters you have, what happens to them, their close calls and easy victories,” he said. “I didn’t want to get in the way of that, so I focused on passive, exploration-based narrative to introduce the players to the world.”

The roguelike genre first emerged in the industry during the late 1970s and early 1980s, when titles such as Rogue (1980) and Beneath Apple Manor (1978) introduced procedurally generated content as a tool in game design. Because no two games could be played the same way, each runthrough possessed individual challenges, victories, and defeats. This meant that every player essentially built their own story as they played, with all the victories and tragedies unique to their protagonist’s experience.

Indeed, because roguelikes are largely driven by procedurally generated content, passive storytelling is an extremely popular approach to worldbuilding in the genre. Take the player character Rogue, from Vlambeer’s 2015 shoot ‘em up Nuclear Throne. Very little is known about Rogue when the player first unlocks her. It’s the contextual clues about her identity that help the player fill in the blanks. She clearly is a former member of the Inter-Dimensional Police Department (or IDPD), due to her blue police uniform. She can’t speak the post-apocalyptic Trashtalk jargon, suggesting that she hasn’t been in the nuclear wastelands for long. The IDPD constantly gives chase to her, implying that Rogue’s former employers are not happy about her sudden departure. Most noticeable of all is the change in level music for her penultimate return to the IDPD headquarters, suggesting something foreboding about her reappearance.

Nuclear Throne never tells the player these things outright, though. Instead, every player ends up creating their own stories about Rogue. Some see her as a scorned police officer thirsty for revenge. Others say she is uninterested in her past, and simply eager to discover the secrets of the Nuclear Throne. Either way, no two fans view Rogue the same way. The game leaves its lore up to the player’s interpretation as they play through the game.

In the same way, Bunker Punks isn’t interested in hand-holding the player through the why’s and what’s of its world. Instead, the game gives the player a base of operations, a gun, a player character, a premise, and an enemy to kill. The rest comes through in bits and pieces, vis-à-vis the player’s actions. Reading Fero’s advertisements reveals the proxymen’s true nature, for example. Character bios provide additional backstory regarding the Zero Sum Gang’s history and Fero’s nefarious deeds. By simply playing through the world, the player comes to learn how determined Molly Pop and her allies are to destroy the megacorporation from within—even if that means losing their own comrades in the process.

///

Despite its popularity in roguelikes and action-adventure titles, videogaming isn’t the only art form interested in environmental storytelling. In fact, musicians are often fascinated with the subtext behind the worlds they build, too.

In 1975, Bruce Springsteen released Born to Run, one of the most critically acclaimed albums of his entire songwriting career. The album continued a longstanding trend in Springsteen’s discography of referencing locations across New Jersey. In particular, Springsteen’s closing song, “Jungleland,” features a 9 minute and 34 second ballad about street life in the Garden State and New York City during the mid-1970s.

Springsteen never directly states where “Jungleland” takes place, however. Instead, clues are dropped throughout the story—Flamingo Lane seems to be referencing the Flamingo Hotel in Asbury Park, and the “giant Exxon sign that brings this fair city light” appears to be an actual Exxon sign in the town. Each of these objects and symbols paint a larger picture of an area drowning in sorrow and despair, and Springsteen allows the listener to fill in the blanks themselves. Every story becomes a personal one about isolation, desire, and loneliness in mid-20th century American life.

Granted, when Springsteen sat down to record Born to Run, he certainly didn’t have the fledgling videogame industry in mind. But his approach to storytelling—one based around a gradual introduction to locations through symbolism and description—mirrors the roguelike genre in its own right. And both videogaming and music draw on the senses to orient their audiences into their artists’ worlds. Again, this is no coincidence. In fact, it’s quite a natural way of processing information.

According to Karl Kroeber’s 2006 work Make Believe in Film and Fiction: Visual vs. Verbal Storytelling, perceiving one’s environment is “psychosomatic” in its functioning. Referencing Raymond Williams and J.J. Gibson, he explains that human psychological perception is a “proactive process for entering into the environment, orienting ourselves, exploring, investigating, seeking.” In other words, human psychology is based entirely on environmental exploration and investigation. Therefore, Gibson’s theories suggest that environmental storytelling is a natural way of processing information, because the human mind is hard-wired to engage with objects while in motion. After all, as Williams says, “new facts about perception [are] a determining relation between neural and environmental electrons.” Humans build meaning from new information about their environments, as opposed to static descriptions of individual locations.

“Registering movements with acuity facilitates our exploring of our environment, actively entering into reciprocal engagement with it,” Kroeber states. “The most common and ingrained mistake about our perceptual systems is to think of them as passive, as mere receptors.”

Granted, Kroeber’s work focuses largely on visual processing in film criticism. But the body’s ability to process and understand information is, psychologically speaking, the essence of human life. In other words, as people, we want to learn more about our environments by experiencing them. Whether that’s a nuclear apocalypse, or an urban wasteland, artists that leave their work up to interpretation end up appealing the most to their viewers, listeners, and players by mimicking the ways our brains naturally function. They replicate real world psychology through art.

///

Much has changed since Shane Neville first began working on Bunker Punks in 2014. Back then, the Obama administration was still halfway through its second term in office. Edward Snowden’s NSA leak had just changed the landscape of Internet privacy. Drones were a looming concern, but few thought they were anything more than a science-fiction dream. “Presidential Candidate Donald Trump,” was a punchline, not an anxiety. Now that Bunker Punks has entered Steam Early Access, Neville’s game is in a very different world.

“In the process of building a science-fiction setting, sometimes the fiction is too close to reality, and instead of being fiction it becomes satire,” Neville said. “Two years ago, I had this idea that the richest people in North America would build giant walls to keep out poor people. Now, this has become a campaign promise. Unplanned or not, it suddenly became satire.”

More than ever, Americans are afraid of the rise of megacorporations. In a game where downsized workers become cyborg henchmen, and wealthy businessmen dictate when its wage laborers should consume, Bunker Punks finds itself in a political environment ripe for its story. Neville’s world captures the issues driving at the heart of today’s recession.

But perhaps this is the very nature of environmental storytelling in roguelikes. Instead of telling a linear story, Neville has simply given his players the opportunity to fill in the blanks with their own narratives. It means that each runthrough of Bunker Punks becomes a personal story for the player—with all the highs, lows, and political anxieties it may involve.