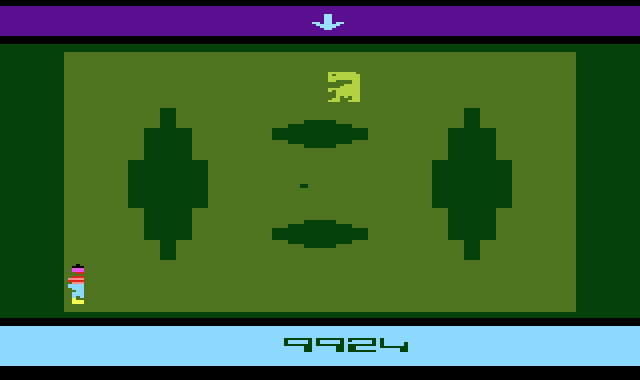

E.T. for the Atari 2600 is largely regarded as the worst game of all-time. It is reputed to have single-handedly wiped out the videogame industry in 1983, led to the demise of the first great game company Atari, ruined millions of kids’ Christmases, and later to have had millions of unsold copies buried in the desert. There is a fine line between “It’s so bad, it’s good” and “It’s so bad that it nearly killed a new medium,” and E.T. crossed it.

Nearly 30 year after the fact, we caught up with Howard Scott Warshaw, the sole programmer and designer of E.T., to see how the fallout affected his life. It turns out, he spent years searching for what to do next, flirting with filming-making and BDSM, before deciding to become a therapist for the Digital Age.

I’m sorry to start off on a down note, but I think we must talk about E.T.. From what I understand, you had a little over a month to work on it. What were the working conditions like? Was it hell?

Pretty much. It was non-stop. I actually had a development system moved into my home. I would bounce back and forth between work and home and just keep working. It was a grueling five weeks. I was trying to innovate with it as well. I tried to do more than was possible. I generated a game that was a pretty good game–uh, it was the root of a pretty good game. I didn’t have time to tune it, and that was unfortunate. Is it the worst game of all time? Probably not. But I like it when people refer to E.T. as “the worst game of all time.” I prefer that to: “Eh, it’s just a bad game.”

E.T. is often cited as one of the contributing factors to the video game crash of 1983. Is that fair?

It’s easy to point to one game and say, “Oh, this is it. This is the thing that crashed the industry.” While I’d like to think I had that much power–that with 8k of code I could actually destroy a billion-dollar industry–I don’t think it’s fair. People want a reason when big things happen, and E.T. is a very isolatable, easy-to-focus-on thing where you can go: “This was a big failure. Look how bad this looks.”

They don’t talk about Pac-Man, the Atari 2600 Pac-Man, which may have lost even more money, and created more resentment and disappointment. They don’t talk about the fact that Atari’s business practices were very heavy-handed when they were succeeding. They were doing a lot of things that were really aggressive, like forcing distributors to eat dead product in order to get hot product. So, as soon as things started to turn against Atari, everybody jumped on them with both feet.

Did you take any heat for E.T. from Atari?

Not really. The company knew what they were doing. They were the ones who negotiated the deal–spending 22 million for a movie property. It was absurd.

They paid 22 million for the license?

They paid 22 million for the rights to do the E.T. videogame.

Jesus.

They were just trying to beat out Coleco. It was silly. They had an ego about who was going to handle the big properties. And so they overpaid for it and left too little time.

The videogame market crashed in ’83. It didn’t end on a high-note for you. Did it take you a while to get over it mentally?

I did need time to get over it. I left Atari in ’84, shortly after they were converted into the Tramiels. That made it… just not the kind of place you wanted to be anymore. The thing that I needed to get over was the whole experience of having been a young guy out of school and getting the opportunity to do exactly the kind of work I wanted to do–real-time microprocessor control programming, which is a fascinating type of work–and then having that turn into a new medium and success and money. And then to have it all disappear and fall apart….

Atari was the ultimate grand slam for me. When that fell apart, there wasn’t another place to go that was anything like that. There just wasn’t. I had achieved a significant amount of fulfillment for a little while, and then it was just gone. That was pretty hard for me to deal with.

So what was going on in your mind at that time. It seems to me, looking at the course of your life, that you were searching.

There was a lot of searching. I had huge financial issues. A lot of the money went away because of tax issues. It was a search to find what I wanted to do. I got a real estate broker’s license. I went in and out of games, and in and out of other industries. I would do creative stuff. I did some writing and photography. I went into filmmaking.

I came to a place in my life where I decided, you know, I really didn’t have anything else going. Nothing was really happening, and I wanted to do something more affirmative. When I thought about it, I really wanted to be a therapist. I was the one among all of my friends who people talked to if they had a problem. So I went to school, and I’ve just about finished my 3,000 hours that you need to qualify as a therapist in California.

That’s a huge accomplishment, but before we get to that, I wanted to ask you about one of your movies called Vice and Consent.

Vice and Consent is a documentary I did about the San Francisco BDSM or “kink” community. It’s about alternative sexuality. San Francisco is one of the capitals in that community. I thought it was interesting because a very close friend of mine–someone who I had known for decades–got very into it, and they were telling me what it was like. I think of myself as a pretty open-minded, non-judgmental kind of guy. But, uh, what I was hearing from her was way different from what I had expected. I thought I had an idea of what that kind of stuff was about, but I realized what I thought was wrong.

I like documentaries when there’s a secret truth, or something that’s really misunderstood or unknown. Also, it has a sexuality thing, and I was curious about it myself. I thought this would be a great way to achieve a lot of ends. As I did the documentary, I found that I wasn’t as interested in [BDSM] as I thought I might have been, but I was actually very interested in the people who were involved in it, because they really are amazing people. Not unlike at Atari. Atari was a collection of amazing people, and here was another chance for me to run into remarkable, interesting people. I didn’t get nearly as into the activities as I might have, but I did find a lot of friends who I really value.

You mentioned that people have misconceptions about BDSM. Could you go into that a little more?

There are huge misconceptions about the BDSM community, particularly about S&M, which people think is about pain and punishment and torture, when, in reality, it’s about trust and consent and intimacy–and primarily endorphins. People negotiate exactly what they’re going to do, talk about precisely what’s going to happen, and make sure everyone is okay. They check in with their partner along the way, and a lot of work is done to ensure that it’s a safe, controlled exchange. There are a lot of dramatic elements to it. There are things that are made to look like they are more extreme than they really are. That’s part of the thrill. But what’s important to remember is that the people who engage in this kind of activity are doing it in a loving way.

These people have a different kind of sexuality that they express. A lot of people say that the BDSM world is very much like the gay world was 30 years ago. The gay world has made a lot of progress in terms of having people understand that they aren’t a threat to anyone. The BDSM community is still fighting that battle. It’s a tricky place. They aren’t doing anything wrong. They are only engaging in it with people who also want to participate in it and enjoy it. But everyone wants to tell them that it’s wrong, that they’re wrong for doing it, and that they have some kind of problem. That’s a hard place to be in life.

Is that something that you specialize in with your therapy practice?

I definitely do. There are a number of specialties that I have. My primary one is working with technology people–working with engineers who have trouble relating to people. There are quite a few engineers who are like that. A lot of people get into computers to avoid people. Some engineers have difficulties in relationships. I am able to connect with and work with those kinds of people, having been an engineer and now being a therapist.

Whereas a lot of engineers are very resistant to therapists, because they see them as these whacked-out, weird, woo-woo types who are touchy-feely and don’t know anything about the real world, I do therapy with engineers like an engineer. I give them engineering metaphors. I can talk systematically about their mind, and how it works, and make it sensible to them. It’s been very effective.

Are they just shy, or is it more than that?

There are a lot of reasons why someone might avoid people in relationships. Part of it is past trauma. Part of it can be phobic reactions. Some of it could be shyness. Some of it could be people who are on the autism spectrum–people with mild Aspergers. There are all different facets of people who will seem resistant socially. Each of them has a different reason for working that way.

What about the profession draws these types of people?

It used to be accounting and actuarial science. That’s the traditional stereotype of people who aren’t good with other people. Programming a computer opened up a whole new branch of that, because the computer isn’t like a person at all. A computer gives you consistent, reliable feedback. It doesn’t change its mind on you. It doesn’t play political games. It just does what it does.

Programming has also become a very lucrative profession. Programmers start making some money, and suddenly they’re more attractive to people in social dealings, but they’re not always able to participate. It turns out there’s quite an overlap between people in technology and people into alternative sexuality too.

You wouldn’t expect that at all.

In the alternative sexuality community, one thing that people really like to do is create toys and machines to enhance their sexual encounters. What you find is that engineers are very interested in that kind of activity. So, there is some crossover. And there are people who don’t cross over. I do a lot of work with couples and some family work. Those are the kinds of things I specialize in.

Would it be fair to say that you’re like the boy from E.T.? You’re the only one who can communicate with this other side of people.

That’s an interesting way to put it. I do bridge worlds. If you look at Elliott from E.T., he was a facilitator. He was the one who was able to help E.T. connect with the world in a more peaceful way, and to get back to where he needed to be. I’d say I play that role.

How did your past with videogames prepare you for becoming a therapist?

It taught me to look at systems, and see how people tend to approach things. A game is a set of rules with an objective, and, if you think about it, that’s like a microcosm for life. Most people who have issues do so because they have created a set of rules for themselves, but their set of rules isn’t necessarily appropriate. What I do is help people work through their rulebook and get rid of the ones that are unnecessary.

It sounds like the videogame industry needs a good therapist.

Well, I’m here.

Additional reporting by Rachel Helps.