If you want to make something in a videogame, you can. Of course, you need to know how to code and there has to be a vision, but in a digital space restrictions like gravity and scope that might interfere with something like film aren’t present. If you can imagine something, you can sculpt it with pixels and perseverance.

In games, as in film, nothing built this way has ever looked completely real.

“You can’t get the same warmth or the same level of detail if you’re using something like Unity or whatever you want to create your 3D world in,” Luke Whittaker, the co-founder of London-based State of Play Games said. “Even a PlayStation 4 can’t produce something that’s indistinguishable from reality. So we just thought ‘Well, let’s use reality.’”

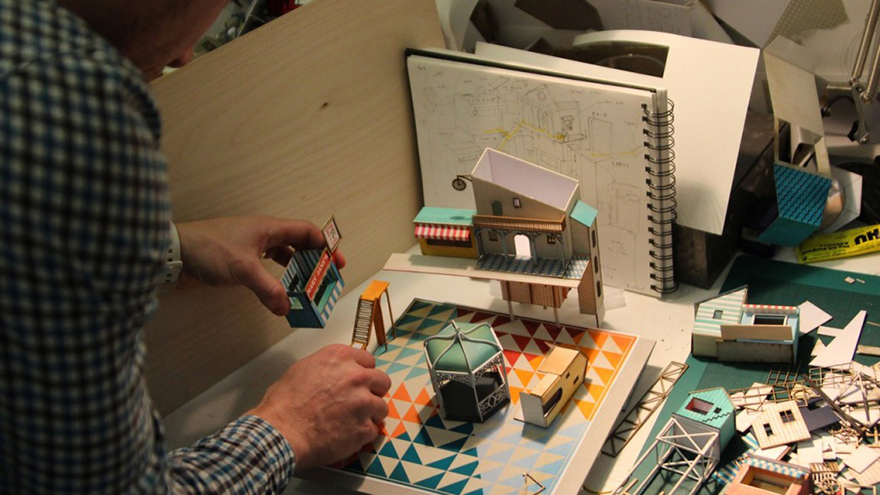

He’s talking about their game Lume and its successor, Lumino City. Both games had their environments constructed in the real-world, and only afterwards were the models filmed and used as the backdrops for their respective titles.

It’s not stop-motion animation, for the most part. Instead, State of Play builds their living, moving worlds from cardboard, laser-cut pieces, found objects and “tick-tock motors” to move about the scenery. In Lume, that meant a single two-foot-wide model of a house. For the sequel, they’re looking a little broader.

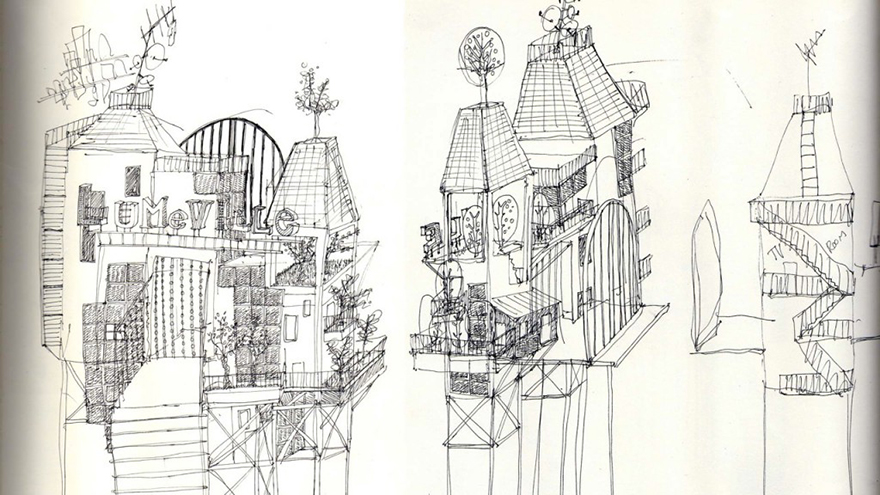

Lumino City is set to exploit the “city” aspect of its title. “Two-foot wide” is now ten-feet tall—with more intricacies and characters than the first. However, when dealing with real objects, a larger scope means a wider margin for error. Working an object by hand brings the risk of making something “not quite right” in a way meticulous digital sculpting doesn’t.

That thought doesn’t seem to concern Whittaker overmuch.

“Even the mistakes you get are quite enchanting,” he continued. Such storybook terms colored almost everything the developer had to say about the game’s look. Based on the original game, and images of the second, I admit they seem appropriate.

“Warmth” was the word he used most often during our interview to describe the impression of real models. “Serendipity,” on the other hand, intimates how even unexpected challenges created a better end product.

“I just finished making a model of a 1950s computer room,” Whittaker explained. “When I started I didn’t quite know what it was going to look like. I didn’t know how I was going to build the chair…”

He went on to describe how the room came together. Metal shavings and leftovers from other structures were collected and cobbled into one.

“It turned into a quite uncomfortable-looking seat, because I just couldn’t find anything to make a cushion out of,” he elaborated. “That ended up making complete sense. It’s a 1950s computer room where the character who lives there has kind of been down there for ages unable to do anything but use old punch cards. In a way, it was like another nail in his coffin – he hasn’t even got a cushion on his seat anymore!”

Luke describes the almost insignificant detail fondly, like a treasured memory. There’s something about building objects with their own hands that appeals to the developers of State of Play.

Whittaker describes the style as “man in a shed” design. Though it was only made to look handcrafted, you can see something similar in LittleBigPlanet, another United Kingdom export.

I asked Luke if there might be a connection. He posited that there is likely a connection between a region’s culture and its game-making practices, just as in any other artistic medium.

“It’s hard to see maybe when you’re on the inside of it,” he admitted. “But I know that looking at games that come from elsewhere there’s a definite feel. Machinarium, for example, I thought that was beautiful when I saw it. I discovered afterwards that there’s actually a big history of Czechoslovakian animation that looks quite similar and that’s part of that cultural history.”

Wallace and Gromit is a similar cultural artifact from British arts, and one Whittaker provides as possible childhood inspiration.

More directly, the developer grew up in a creative household. His father, a designer, and mother, an artist, both came up through the Royal College of Art. Even today, the developer’s surroundings haven’t changed much.

State of Play works out of an abandoned art studio—renting more expensive equipment, like the special camera needed to film the models, when they can afford it. Below them lives a man that makes TV props. Just two doors down from the studio resides an architect from whom they can get more common materials for their work.

Whether their similarities are a result of region or circumstance, each of them works with their minds and hands in one way or another.

The one downside to State of Play’s bespoke style is that Lumino City may take awhile to produce. The game already slipped from a 2013 release window, and as yet there isn’t a new, hard target. Hopefully, warmth and serendipity and will make the wait worthwhile.

“Maybe if we knew it was going to take this long we wouldn’t attempt it,” Luke said.