Header image via Jonathan Visconti

///

It’s a Thursday night and I am following Trevor Philips around Los Santos. If we’re being fully honest, I’ve been following him for a few days now and seen him commit all manner of crimes. I don’t think he knows that I’m following him. At least I hope he doesn’t. Trevor has the gait of a man who is permanently irked, always trundling off to settle one more score. He wouldn’t like to be followed and, based on everything I’ve learned about him, he would be particularly displeased that I can now tell you what his ass looks like.

Trevor isn’t the only character I’ve followed this year. I’ve stood behind quarterbacks as they dropped back to avoid oncoming rushers; I’ve followed the undead through the land of Drangelic; I’ve watched a ranger clamber over fences and towers throughout Mordor. This is how videogames work. In order to see the world through a character’s eyes, you often stand behind her. You control her movements but your body isn’t hers. You are off-screen, a few steps back, taking in the whole scene. This vantage point allows you to observe a scene while also participating in it.

All of this is a roundabout way of noting that a year spent playing videogames is a year spent looking at asses. Not necessarily leering, but definitely looking. The omnipresence of asses affects how players interact with games. In his study of 35,000 MMORPG players, Ubisoft researcher Nick Yee found that men often choose to play as female characters in third-person games because they “prefer to stare at a female body rather than a male body.”

Within a frame, the prominence of an object’s position is usually correlated with its importance—and in a third-person game, the protagonist’s ass is always on display. Yet asses in videogames are rarely taken seriously. They are fodder for lists like The Top-10 Booty Babes in Gaming or The Top 5 Butts in Video Games. On Reddit, there’s a thread dedicated to identifying videogame characters based solely on images of their asses. This form of objectification, like most others, is overwhelmingly directed at female bodies.

This has been a banner year for asses. For much of the summer, the airwaves were battlefields on which competing odes to the power of asses—“Anaconda,” “Booty,” “All About That Bass,” “Wiggle”—fought for supremacy. Whereas previous songs on the topic, such as “Baby Got Back” or “Bootylicious,” felt more like isolated hits, these ass anthems came together to form their own musical movement. This year, the cover of Sports Illustrated’s annual swimsuit issue, which has traditionally featured women photographed from the front, focused on the bottoms of models Nina Agdal, Lily Aldridge and Chrissy Teigen. In July, documentarian Kurt Williams released Bottoms Up, which tracks America’s cultural obsession with large asses and the butt implant industry that has emerged in its wake. This September, the New York Times profiled Jen Selter, whose “belfies” (butt selfies) have earned her more Instagram followers than Barack Obama. Selter can be thought of as a cultural successor to Kim Kardashian. To wit, British tabloid Closer reported “Kim thinks Jen copies all her poses … Kim has sought legal advice to see if they can stop Jen.” The butt bonanza was not limited to women: Cody Simpson and Joe Jonas broke out of their “teen star” mold by posing for ass shots; the butts of actors Charlie Hunnam, Daniel Radcliffe, Jude Law, and Hugh Jackman were all featured in their respective projects.

Asses were everywhere in 2014, but the humans to whom they were affixed had little to say about what this meant. “I don’t know what there is to really talk about,” Nicki Minaj told GQ’s Taffy Brodesser-Akner. “I’m being serious,” she said in reference to the music video for her hit single “Anaconda,” in which her ass causes earthquakes and forces Drake to hang his head, cowed, “I just see the video as being a normal video.” When asked about the increasing importance of butts, Kim Kardashian told an Australian TV host, “I don’t know if it’s trendy, I wouldn’t say I started a trend.”

Many videogames share in this tendency to display asses while suggesting that they mean nothing. But, in 2014, some of the most interesting ideas about asses could be found in videogames. More specifically, two games—Bayonetta 2 and Hurt Me Plenty—suggested that the ass’s prominence is not simply a visual tic; it is an important idea and a way to think about the distribution of power within a game’s universe.

///

Ass is not an anatomical concept. You will not find it listed in the 13,000-entry index to Henry Gray’s seminal tome, Anatomy of the Human Body. But the human body isn’t just a physical reality, it is also a series of ideas. “The body becomes a choice,” writes Judith Butler in Sex and Gender in Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex, “a mode of enacting and reenacting received gender norms which surface as so many styles of the flesh.” In that spirit, ass is clearly associated with a part of the human body (butt, buttocks, posterior) but is really an idea, a catch-all term for the power—cultural, physical, political, or sexual—that is ascribed to the anatomical region.

As with most forms of power, ass is a gendered concept. The qualities attributed to male and female asses rarely overlap and, in so doing, are indicative of broader societal power imbalances.

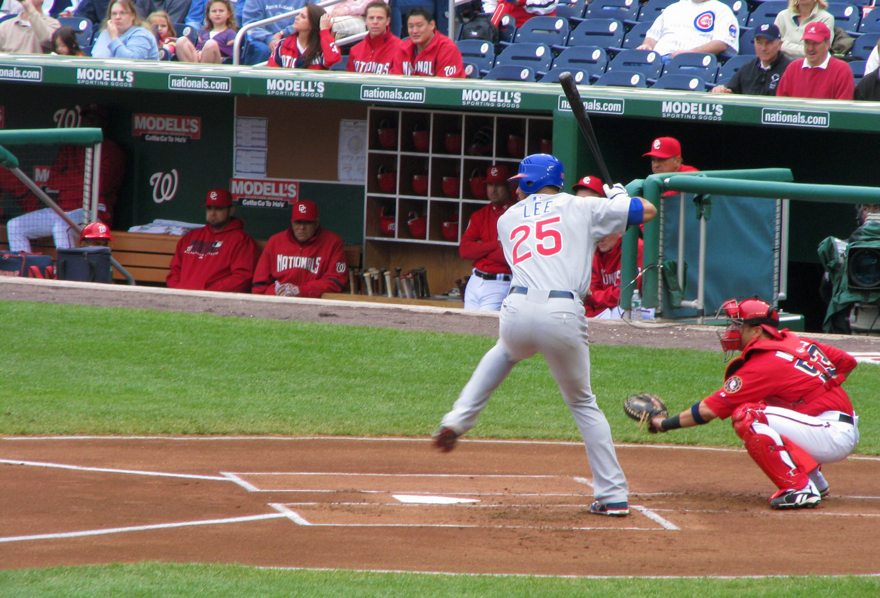

Perhaps the biggest sign of this imbalance is that the male ass is not universally regarded as an erogenous zone. This allows it to be discussed in cold, dispassionate terms. Baseball scouts, for instance, spend a good deal of time thinking about the shape of male asses. In Michael Lewis’ Moneyball, the debate between old-school scouts and Billy Beane’s band of progressives is typified by a discussion about asses. One of the Oakland Athletics’ seniormost scouts describes Jeremy Brown as “huge in the ass,” implying that he is overweight and doomed to be an athletic failure. In response, Beane asks if Jeremy Brown can hit, suggesting that idealized notions of the human body can be deceiving. This is the crux of Moneyball. Lewis writes, “For Billy… a young player is not what he looks like, or what he might become, but what he has done.” In their own ways, both camps are arguing that a man’s ass is an indicator of his physical and athletic prowess. The question is, what does the shape of a man’s ass mean?

According to Buck Showalter, the manager of the Baltimore Orioles, players with flat butts stand no chance of making the major leagues. Instead, the platonic ideal is a player with a prominent, high butt. If that ideal had a name, it would be Derek Lee, about whom Showalter once said, “I don’t want to say he’s got a perfect butt, but when I look at it I say wow.” As a sport, baseball is hardly unique in its obsession with male asses. In endurance cycling, where every extra pound is a weight that has to be dragged up hills, the ass, like most of the body, is the enemy. In his autobiography, The Secret Race, the disgraced cyclist Tyler Hamilton writes that he knew he was in shape “when it began to hurt when I sat on our wooden dining-table chairs. I had zero fat on my ass; my bones dug into the wood and they ached; I had to sit on a towel to be comfortable.” The disappearance of Hamilton’s ass was a symptom of his pre-race weight loss regime. “Friends would start to tell me how shitty I looked—that I was just skin and bones,” he recalls. “To my ears it sounded like a compliment. I knew I was getting close.” Hamilton’s butt, like those of Derek Lee and Jeremy Brown, speaks to his overall physique. The asses of male athletes garner attention but they are rarely disembodied.

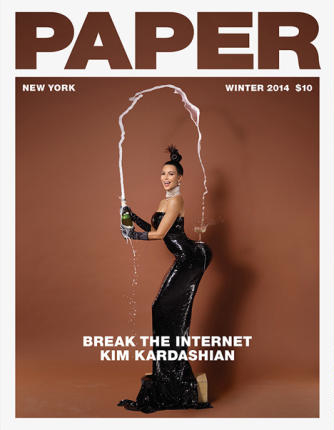

While female asses are powerful cultural signifiers, the women to which they are attached less frequently benefit from this power. The possible exception to this rule is Kim Kardashian, who has parlayed it into an impressive reality television and business empire. For much of her public life, Kim Kardashian has struggled to gain acceptance in the world of fashion. This is but one of the places where having an ass can count against you. Perhaps that is why she agreed to be photographed by Jean-Paul Goude for the three-decade-old fashion magazine Paper. The magazine’s cover was a portrait of Kim shot from behind focusing on her naked, callipygian form. It is nothing if not impressive, the sort of image that dares you to describe it in the language Tom Junod uses when talking about women over 40. Inside the magazine, Kim balances a coupe on her posterior and holds a bottle of champagne in front of her. The champagne shoots out, arcing over her head and into the coupe. It’s as if the champagne’s bubbles are the internet’s eyeballs, pruriently drawn to the image. Paper promoted the spread with the tagline: Break the Internet.

While female asses are powerful cultural signifiers, the women to which they are attached less frequently benefit from this power. The possible exception to this rule is Kim Kardashian, who has parlayed it into an impressive reality television and business empire. For much of her public life, Kim Kardashian has struggled to gain acceptance in the world of fashion. This is but one of the places where having an ass can count against you. Perhaps that is why she agreed to be photographed by Jean-Paul Goude for the three-decade-old fashion magazine Paper. The magazine’s cover was a portrait of Kim shot from behind focusing on her naked, callipygian form. It is nothing if not impressive, the sort of image that dares you to describe it in the language Tom Junod uses when talking about women over 40. Inside the magazine, Kim balances a coupe on her posterior and holds a bottle of champagne in front of her. The champagne shoots out, arcing over her head and into the coupe. It’s as if the champagne’s bubbles are the internet’s eyeballs, pruriently drawn to the image. Paper promoted the spread with the tagline: Break the Internet.

So it did, if you view the Internet as a collection of essays. Writing at The Grio, Blue Telusma noted that Goude’s work emulated Saartjie Baartman, a Khoisan woman who, due to her large behind, was brought to Europe and put on display in the early 19th century. Baartman, Telusma writes, “was a woman whose large buttocks brought her questionable fame and caused her to spend much of her life being poked and prodded as a sexual object in a freak show.” Moreover, as Neelika Jaywardane notes, “[Baartman’s] European audiences viewed themselves against the savage/colonised other’s bodily difference … in order to fulfill their desire to amalgamate their self-view as the ‘norm’.” Much of the power Baartman had over the audiences that came to see her was ultimately used against her.

The debate over Saartjie Baartman’s legacy that emerged in the wake of Kim Kardashian’s Paper spread suggests that our conception of the power of female asses hasn’t evolved much since the 1810s. Asses still have the power to attract eager audiences but it’s not clear what benefits come with that power. Baartman’s possibilities were literally limited by the same institutions that put her on display and made her an attraction. Kim Kardashian has the distinct benefit of not being a colonial subject but her public life has been one long quest to demonstrate that ass translates into real power. As she tweeted when the Paper cover was first released: “And they say I didn’t have a talent.”

///

The videogame analogue to Kim Kardashian is not Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, the game in which players seek to transform their avatars into Kim-like celebrities. Characters in the game are only shown from the front, as if to envision a world in which fame is a concept that has nothing to do with asses. This omission is an interesting commentary on ass in its own right but it is a fantasy. Rather, the heir to Kim Kardashian’s contradictions is Bayonetta—a fantasy of a very different sort.

Bayonetta 2 is an orgiastic assault on the eyeballs. Everything is in your face: Dragons! Fighting! Guns! Angels! Bayonetta! Bayonetta’s ass does not escape this maximalism; It is not of this world and neither is she. A human of her proportions could only be produced in a taffy stretcher. In a game that likes to foreground everything, Bayonetta’s posterior is particularly prominent. It is always there, wrapped in a dominatrix outfit, as she fights off foe after foe. The question with Bayonetta, as with Kim Kardashian and Saartjie Baartman before her, is whether her physical presence is a sign that she has power within her world.

The simplest answer to the question is that Bayonetta’s showmanship is proof that she is a willing participant in this act. She plays to the game’s imaginary camera. She knowingly winks at it. Jezebel’s Cleuci de Oliveira described Baartman in similar terms, as someone who “viewed herself as a performer.” But it’s a mistake to focus merely on Bayonetta and Baartman’s abilities as performers. Doing so ignores the context in which such performances exist. “As a poor woman, and as a woman,” note Baartman’s biographers, Clifton C. Crais and Pamela Scully, “the parameters of her being able to control her life were quite narrow.” Baartman’s stage presence in no way made up for the ways that society deprived her of political power or meaningful bodily autonomy. Does the same hold true for Bayonetta?

The problem with this parallel is that Bayonetta is comparably privileged. Within Bayonetta 2’s universe, she is white, not visibly impoverished, and not a colonial subject. Bayonetta is not immune from sexism or oppression but thinking of her as a “modern day Saartjie Baartman” does a disservice to all parties involved. The bodies of women like Saartjie Baartman were used against them as a tool of oppression. Bayonetta or white pop-stars who show a sudden fascination with asses are unburdened by this legacy. Bayonetta’s whiteness is not proof that she is not oppressed but, insofar as the history of the buttocks is in part a history of racialized bodies, it is a non-negligible advantage.

The political realities of Bayonetta 2’s universe are far from clear. This is a world with little respect for laws of any kind, including those of physics. But the physics of Bayonetta 2 are the biggest indicators of the titular protagonist’s power. If the normal human body rotates and bends about the waist, Bayonetta’s main axis is her ass. Everything moves and follows from it. Her legs appear to have sprouted from it. Everything in Bayonetta 2 orbits it like the planets follow their trajectories around the sun. Garish though it may be, the game’s visual language effectively establishes that Bayonetta’s ass trumps all.

Bayonetta 2’s imagery is definitely sexual—what little clothing Bayonetta wears appears to be made of leather or spandex—but her power over others is not purely erotic. In many ways, Bayonetta has more in common with the baseball players Billy Beane and Buck Showalter discussed than Kim Kardashian. Her ass is a sign of her physical ability. Who else could bend over backwards and spin around as she does, let alone with so much grace? Bayonetta doesn’t simply dominate the world around her in the sense that she is a dominatrix: her ass is a symbol of her physical primacy within the game’s world.

///

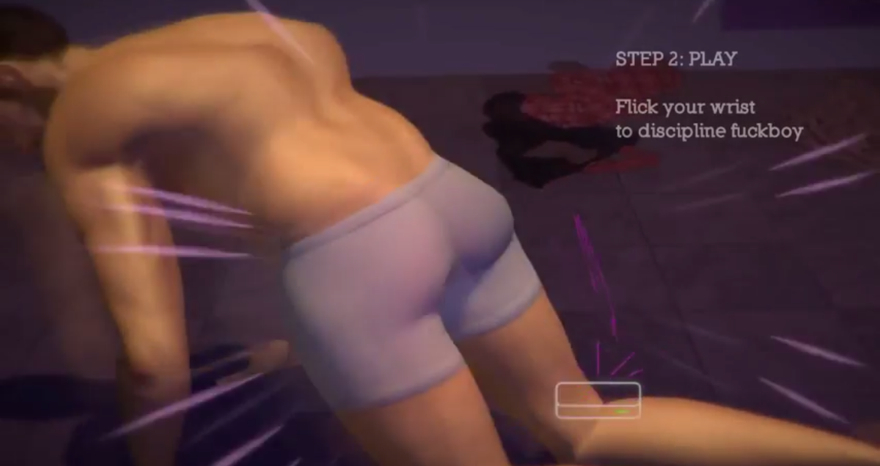

It is fitting that the games that engage most fully with issues of power are inspired by BDSM. In the case of Bayonetta 2, this connection is largely visual; the game owes some of its imagery to the world of BDSM, but its ideas are from the world of anime. Hurt Me Plenty, on the other hand, is a game imbued with the ideas of power play and BDSM. As a game about spanking, it is also all about ass.

The man whose ass you spank in Hurt Me Plenty has no name. On the game’s website, he is only referred to as a “dude.” He is a piece of ass in the most literal sense of the phrase. But that ass is not simply yours to spank; consent with the dude must be negotiated and can be withdrawn at any time. (Would that the entire world treated consent in the same mechanical terms as Hurt Me Plenty!)

Hurt Me Plenty is a game about consent but, at its most basic level, it is a game about power and how it is allocated within a relationship. The dude has something that you, as the player/dom, want to spank, and as a result he has all the power. Terms are negotiated but the negotiation is primarily a way of ensuring that you know what the dude’s limits are. If you ever exceed the agreed-upon parameters, you find yourself banned from playing Hurt Me Plenty for hours. The dude may be the sub but he holds all the power.

At every turn, Hurt Me Plenty asks you “what you would do to spank the dude’s ass?” Beyond serving as a mechanism to formalize consent, the negotiation is also a test of your interest. Each term you assent to is a positive vote in a one-person plebiscite. Like Bayonetta’s, the dude’s ass occupies the screen but here it says little about the rest of the body; it is a powerful sexual object in its own right. The dude is otherwise unexceptional, but that’s beside the point; this is a that game focuses on the ass. Instead of having to be a symbol of something else, like the asses of baseball players, this ass is simply about ass.

Hurt Me Plenty and Bayonetta 2 invoke BDSM because its language directly addresses sexuality and the line between empowerment and subjugation. Much as dom/sub arrangements require such explicit discussions, so too does topping/bottoming for gay men. (Queering these games is an interesting idea that merits an article of its own.) The issues these discussions seek to resolve exist in all relationships but many non-bdsm, straight couples can avoid directly confronting these subjects. They have the worst vocabulary for discussing issues of power. Without such explicit language, it’s difficult to know who is emancipated and who is a pawn. The various ass anthems that came out this year played into that ambiguity; they highlighted the ass but lacked the vocabulary to explain its power. “Anaconda,” despite being a song about the effects Nicki Minaj’s ass has on men, does not explain how she feels about this power, just that it exists. Hurt Me Plenty and Bayonetta 2 are not directly in conversation with Nicki Minaj’s work—in all likelihood she has played neither game—but they point to a different path for talking about asses in popular culture—one in which physicality, sexuality, power, and history can all be combined.