How are presidents selected?

— How much time do you have?

A stylized sketch of how presidents are selected might go something like this: Candidates choose to run for one of two parties, raise money, compete in a series of caucuses and primaries to win delegates, and the candidate with the most delegates at each party’s convention becomes said party’s nominee. The nominee who picks up the most Electoral College votes in the general election then becomes president. That sketch leaves out the vagaries of political financing, third party candidacies, the curious sequencing of primaries, and superdelegates, but it normally gets the job done.

As with any system that straddles the line between the explainable and the outright byzantine, it doesn’t take much for the whole thing to descend into pure farce. Maybe it’s a candidate too rich to be disciplined by party or private interests. Or the untimely passing of a Supreme Court justice. These aren’t the most crazily unforeseeable of events, but they’re more than enough to disturb the quasi-natural equilibrium. (You can call it a constitutional crisis, if you so choose.)

This predicament ought be familiar to game aficionados. Games also depend on the line between the explainable and byzantine not being crossed. They are engineered to ensure that calamity does not regularly ensue but, at a certain point, depend on all participants to act within reasonable parameters. One might therefore expect games to be good at capturing the dynamics of the current campaign. At least when it comes to weirdness, that expectation is largely borne out.

Exhibit A: Stardock Entertainment’s The Political Machine 2016. The game treats the current campaign like a game, because that’s what is. Probably. Anyhow, you can play as the roster of current candidates or create your own. The game’s aesthetics dictate that all candidates look like they were hand formed from soft putty, but that does not mean the game’s in the tank for Ted Cruz. You can do all sorts of campaign-y things, like “mudslinging” or spending truckloads of money. There’s also an element of strategy because the campaign in The Political Machine 2016 isn’t about ideas—ideas, what are those? Traditional game elements like life bars are easily transformed into polling interfaces. If anything the transformation of game elements into election elements happens a bit too easily. At the end of the game, a candidate wins. It’s a game; there must be a winner.

The Political Machine 2016 does not make enough of a statement to be truly satirical but it can hardly be mistaken for a documentary piece. Rather, it is a reasonably accurate sketch of political life that thinks the whole enterprise is silly. The Political Machine 2016 traffics in a sort of cynicism about politics that serves mainly to prove its own cleverness. It is witty in the same way political foes enjoyed Antonin Scalia’s dissents: a series of clever turns of phrase praised without reference to the underlying point. Fine. It’s still interesting to see a campaign so easily transformed into a game, The Political Machine 2016 feels like something of a missed opportunity.

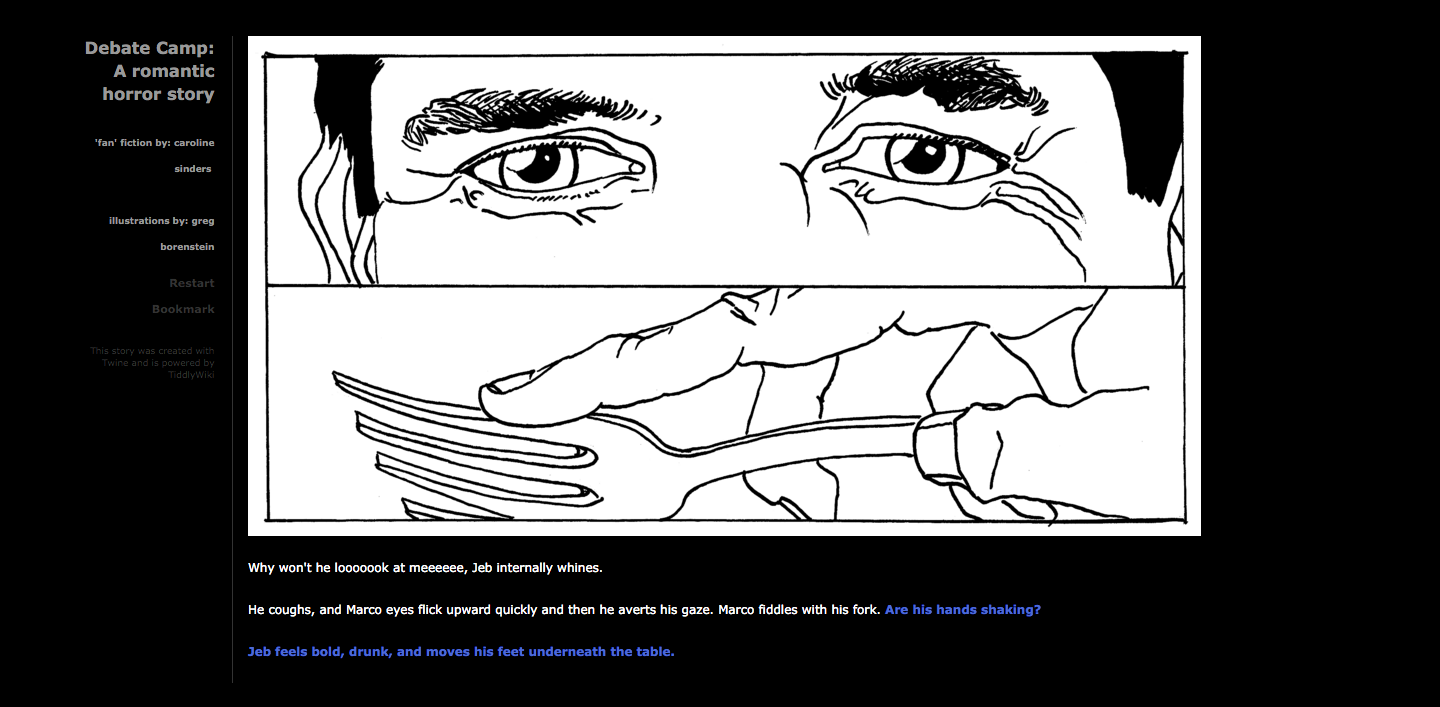

Exhibit B: Debate Camp: A Romantic Horror Story does not hold back. The choose your own adventure game asks one simple question about the Republican presidential aspirants: What if they’re secret lovers? To be clear Debate Camp’s developers, Caroline Sinders and Greg Borenstein, are not implying that the likes of Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, and Donald Trump are secret lovers. Theirs is a work of interactive fan fiction. Like X Factor contestants, the Republican hopefuls have been taken to a cave to prepare for the big stage. A few differences from the X Factor do present themselves. First: Dick Cheney occupies the eminence grise role in Simon Cowell’s stead. Second: The candidates are doing debate prep instead of ballad rehearsals. Debate Camp’s central conceit, however, is that all camps are broadly alike. They are all spaces where you ostensibly work on a skill but really serve as emotional pressure cookers. Debate Camp’s titular camp is not all that dissimilar from band camp or the space camp I once attended.

Debate Camp functions on a number of levels. It can first of all be read as a commentary on policies many of these characters have championed that force many Americans to live repressed lives without a full compliment of freedoms. The game turns that dynamic on its head: suddenly Marco Rubio is the one who suffers. Yet Debate Camp can more accurately be read as a story of yearning. It isn’t so much about sex or sexuality as it is about the deep neediness that might compel a person to run for president. Desirable though the job may be, the career path and work that goes into reaching the oval office hardly looks like fun. So why do it? Debate Camp is onto something when it suggests that campaigning is a way of filling some sort of personal void. If you don’t believe that, here’s a gif of Jeb! Bush putting on a hoodie:

In light of this weekend’s news, however, it’s hard to escape the sensation that Debate Camp and The Political Campaign 2016 might both still be trumped (sorry) by Christopher Buckley’s 2008 novel “Supreme Courtship.” It is, in short, the story of a president who, having run out of fucks to give, decides to nominate a Judge Judy-style TV presenter to fill a Supreme Court vacancy. As you might imagine, things snowball, causing much of the American political apparatus to descend into (even more of) a reality show of its own.

“Supreme Courtship” came out just around the time John McCain selected Sarah Palin as his running mate. It was the kind of timing an author can only dream of: a book about kitschy populism going on sale exactly as that strange brand of mavericky [sic] politicking takes off. The curious thing about “Supreme Courtship,” however, is that it remained applicable to the campaigns that followed. The book eerily foreshadows the Trump phenomenon. Buckley offers a very specific critique of American politics that takes on a life of its own. The Political Campaign 2016, on the other hand, offers a very broad critique of the state of electoral politics. Of course its critique will apply to future elections; there is nothing tethering it to this very moment. Debate Camp comes closer to the effect of “Supreme Courtship.” It has a very straightforward and focused point to be made about the world we live in, and that point will likely endure because our world is strange and not because the point itself is overly broad. Political games could benefit from this approach to political commentary.