As someone who’s spent the past eighteen years working on (often contentious) projects dealing with racial issues, filmmaker Whitney Dow is no stranger to shitstorms of backlash. But even he sounded a bit stunned at the level of response his latest, a multiplatform exploration of what it means to be white in America called The Whiteness Project, garnered. “I’ve gotten more love and more hate in the past 48 hours than I’ve ever had in most of my life,” he says with a short laugh. “A lot of people come to the site, see the name, and get offended… But I’ve learned so much in the last few days too, from people just being incredibly open and honest with me about how the project has affected them.”

In 2003, Whitney co-directed a documentary with long time filmmaking partner Marco Williams about the aftermath of the brutal murder of James Byrd Jr. by three white supremacists in Texas. Two Towns of Jasper was controversial before it even began filming, though, since Dow and Williams decided to segregate their crews (one white and one black) in order to interview the racially divided communities.

“Every project I’ve ever taken on has some element of an unpopular idea,” he admits. “People were outraged—that we were perpetuating this division, and why weren’t we including each other? But to me it just seemed like the most logical thing to do. Because white people aren’t going to be honest in front black people. And black people aren’t going to be honest in front of white people… I mean, that’s not a radical idea. I don’t view that as something pejorative.”

Hearing Whitney talk about his projects, a lot of his “controversial methods” can be clarified by this kind of not-so-radical logic. With The Whiteness Project, for example, the prevailing complaint about its offensiveness goes something along the lines of: what’s the point of giving white people a separate platform to talk when they already have every other platform ever to talk? “And my answer to that is, yeah, they have platforms. But they’re not using them to talk about race—about themselves and race,” Whitney says. “Because white people don’t have to, right? White people don’t have to talk about race. We think of ourselves as outside the paradigm. We think of race as something that is an experience of others. We don’t think of ourselves as having this really powerful racial identity.”

The idea for the project really began with that exact sentiment, too. After giving a speech in 2005 on Two Towns of Jaspe Marco and Whitney were asked questions from the audience, “and this 7th grade girl got up and asked me, ‘Whitney, what have you learned about your racial identity working with Marco on this project?’ And I had this weird epiphany where I realized, despite all the work I’d done working on films about race for three years, all the talks and research I’d done—that I didn’t have a racial identity. But at the same time, I thought, well of course I have a racial identity. I’m a white man. I have the most powerful racial identity in America. But until that moment, I’d never fully processed what that meant,” he explains. “That moment fundamentally changed the way I saw the world. I started to realize my race was an active component of every moment of every day of my life, in every interaction I have with everybody. And I thought, what if I can give other white people that experience? Perhaps I’d be doing something about it.”

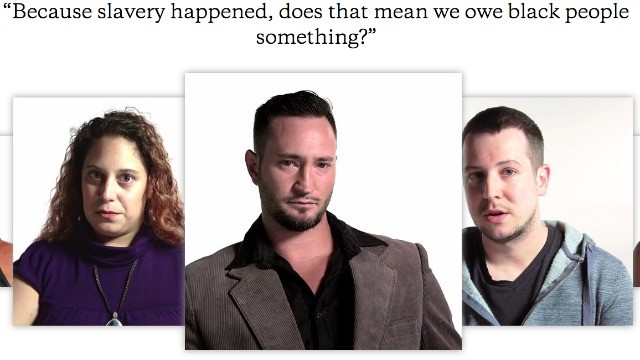

But however logical “white people don’t talk about themselves in the context of race, and should” sounds, nothing could’ve prepared me for the content on the project’s site. If you know anything about the racial situation in this country, whether statistically or through experience, many of these twenty-one interviews with white Buffalo, NY residents will be hard to sit through. “I just don’t buy into the nonsense about discrimination. I mean I feel that everyone is equal. And that’s the way that it should be,” says one colorblind American named Michael. “For some reason, some black people hold on to the back-in-the-day slave thing. Or they feel they’re not being treated right,” says another, Jason. “Should slavery be something that because it happened we owe black people more? Absolutely not.”

At the end of each interview clip, a relevant statistic appears on the screen. “73% of whites believe blacks should receive ‘no special favors’ to overcome inequality,” one reads at the end of Michael’s clip. No further comment provided, just a statistic informing the viewer of a numerical reality of this country. When I asked Whitney how he felt when interviewees expressed sentiments that he (or even the statistics) disagreed with, he insisted that, “I view myself as an advocate for the people who participate in my project. And what I mean by that is my job is not to agree or disagree, but to present them accurately as I understand them.”

Obviously, he says, he disagrees with the idea that whiteness has no privileges. “But I also recognize that [my interviewees] represent a huge chunk of this country who feel that way. And I think that that should be out there, instead of me challenging them and saying, ‘Well, let me school you on that.’ My job is not to school the interviewees. My job is to get a broad representation of ideas.”

Whitney spoke with nothing but appreciation for the people he’s interviewed. He respects their right to an opinion, and applauds them for speaking to him about race honestly when “they’ve often seen anyone who’s white that weighs in on this discussion get absolutely slammed.” He was adamant about this in particular, going on to say people who have experience talking about race shouldn’t “fucking eviscerate any white person who is willing to address these ideas. Give them a fucking break because none of us have that much experience talking about it. So let us talk without gutting us right away. If you want us to participate in changing the racial dynamic in this country that creates things like Ferguson, then you have to let white people feel that they have a vested interest in this conversation. Not that they don’t have a right to speak or to have their feelings—whether or not you agree with them.”

This is where the statistics seem key to the project’s digestibility. Sure, you may (probably) have to listen to some things you disagree with. Experiences and understandings of race are inherently personal ones, since they are about identity. Disagreement is to be expected with any discussion of identity. But, as Whitney says, “you’re still living in a context that can be quantified numerically as a white person. Whatever your personal experience, which is perfectly valid, it’s still statistically an asymmetrical structure out there.”

Understanding Whitney’s intentions with The Whiteness Project seems in a way dependent on the viewer knowing that he believes “that white people and particularly African Americans have such a different experience living in the world on a day to day basis, that we’re fundamentally living different realities. And a lot of times, the confusion that we have when we talk to each other about race is that we’re talking about two totally different things.” One of those fundamental differences, which according to Whitney can cause a lot of miscommunication, is the fact that “whites tend to see race as an individual relationship. And people of color tend to see it as a group relationship. So white people can’t process—or it’s much harder for us to understand the macro of a relationship between a white person and a black person.”

Another facet of the racial dynamic that Whitney says he’s discovered through the project is that “white people are very tied up in their understandings of themselves in their relationship towards black people. In 80% of the interviews, I ask people to talk to me about whiteness and they talk about black people. It’s in our racial DNA—our relationship to anyone who’s not white—the foundation of that relationship in America comes from our relationship with black Americans. Because we started this country together.” It’s a realization reflected in one of Whitney’s favorite pieces of feedback, from a black woman who wrote “I find it interesting that most people on the website right now are talking less about their experience as white people in general, and specifically about their experience as people trying to understand their place vis-à-vis black people. It’s interesting because speaking from my own standpoint, I have trouble conceiving of myself apart from the concept of whiteness. It seems to me that white and black Americans may be inextricably linked for a long while.”

Realizations like that seem like the ideal experience of The Whiteness Project: understandings that enlighten us to similarities across the racial divide, however twisted they may be. In less pleasant but equally important scenarios, the project forces us to hear the hard truths about each others’ deeply personal (if numerically imbalanced) experiences of race. Regardless of whether it’s easy or hard to watch it, The Whiteness Project services the discussion on race in a crucial way. It forces us to listen to a majority that wouldn’t otherwise be heard fully. Because heard or not heard, this majority exists. And it is a majority that cannot (and should not) be ignored if progress is to be made. “If you’re not allowed to talk about this in a direct way, you’re not going to create an honest dialogue,” Whitney insists. “And when you can listen in on people talking honestly about something, you can have a better dialogue than you and I would by trying to bridge some gulf.”

What Whitney ideally hopes whites can walk away from the project with is “the idea that accepting the benefits of white privilege doesn’t have to be a negative thing. It’s not about inheriting this enormous guilt.” Like the epiphany he had about his own privileged racial identity, the realization can be a source for good—an acknowledgment that can perhaps lead to better overall communication. “I don’t feel guilty about who I am,” he says. “I don’t feel guilty when I say what I believe. And I don’t feel guilty when I say something stupid or wrong that I have to rethink about, and maybe address.”

Whitney has big plans for the project, including a potential mobile studio for easy-access interviews for broader participation, as well as the hopes for conducting 1,000 interviews total. He plans to go around the entire country, and is determined to get a broad scope of socioeconomic backgrounds within the white/Caucasian box.