This article is a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

We tend to think of interactive storytelling as a new frontier, dating only as far back as Zork or role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons. But long before any of those came along, an older form of collaborative interactive storytelling had already shaped a significant part of human history.

The oral tradition features a system of folk tales capable of adapting to many environmental and human inputs. They allow information to flow freely across time and space, the same narratives cropping up in different places, generation after generation. Yet the flexibility of orality also gives them a responsive quality, allowing these stories to alter depending on the specific needs and context of the people telling them.

Through the oral tradition, human beings developed a sense of community, tradition, cultural narrative, and religion. You might even say that this kind of interactive storytelling gave rise to the foundations of organized society itself.

Yet while print later imposed the principles of a singular and definitive author, the impulse for dynamic storytelling never left. Now, with the help of new media, interactive narratives are finally experiencing a resurgence, in everything from RPGs to social media platforms.

“It isn’t an accident that the campfire is our logo,” says Stephen Hood, co-founder of a new web-based storytelling platform called Storium. “This is storytelling in a fairly primal form. We’re trying to inspire and help people, and then get out of their way in order to let natural instincts take over.”

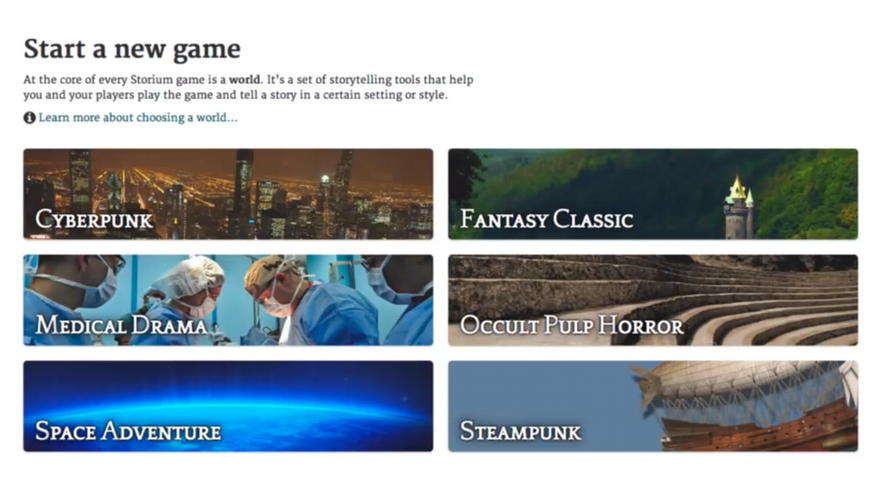

Storium combines the concepts of D&D, format of play-by-post role-playing, and incentive systems of tabletop card games into a new experiment in collaborative storytelling. Players begin by choosing from a library of “worlds” that range in setting, genre, and style. Using these basic story-building blocks, players then create their own characters and plot points, even setting their own pace.

Hood explains that the idea is to “break storytelling down into smaller chunks of creative work, with different contexts and inputs.” Like the responsive folk tales of oral tradition, Storium “sort of puts language and mechanics around the writing. So you can still write whatever you want, but it’s informed by the structure that the game gives you.”

Storium, which has been in beta for several months, aims to deliver on interactive storytelling’s promise of total player agency. Because while videogame narratives often overstate the role of interactivity, tabletop role-playing games like D&D also depend on a game master to play god, lowering everyone else’s control. In order to truly create a balance, the rules of Storium instead “negotiate the passing of the narrative microphone between various players. So as you play, you can actually earn the right to narrate the outcomes of what happens.” Hood cites the new class of tabletop narrative role-playing games like Fiasco as inspiration for “really focusing on game as a storytelling mechanism that gives players and anyone else involved a real sense of agency over their characters and the events.”

Like oral storytelling, the key factor in Storium’s emergent narrative is the decentralization of authorship. Without the constraint of a single input source, these stories are invited to come alive, adapting to the needs of the players at that moment in time. This emergent design also addresses more practical problems, since an asynchronous online game lets “you play at your own pace, it also needs to be designed to fit into—you know—life. Including all the natural interruptions and problems that occur in daily life.”

While Hood believes that “everyone has an inherent storytelling ability,” he’s seen that designated play spaces in games “break down barriers and expectations and judgments that often hold people back.” As a platform, he can only hope that Storium will “provide the room and set the table. But it’s up to other people to come in, sit down, and tell their stories.”