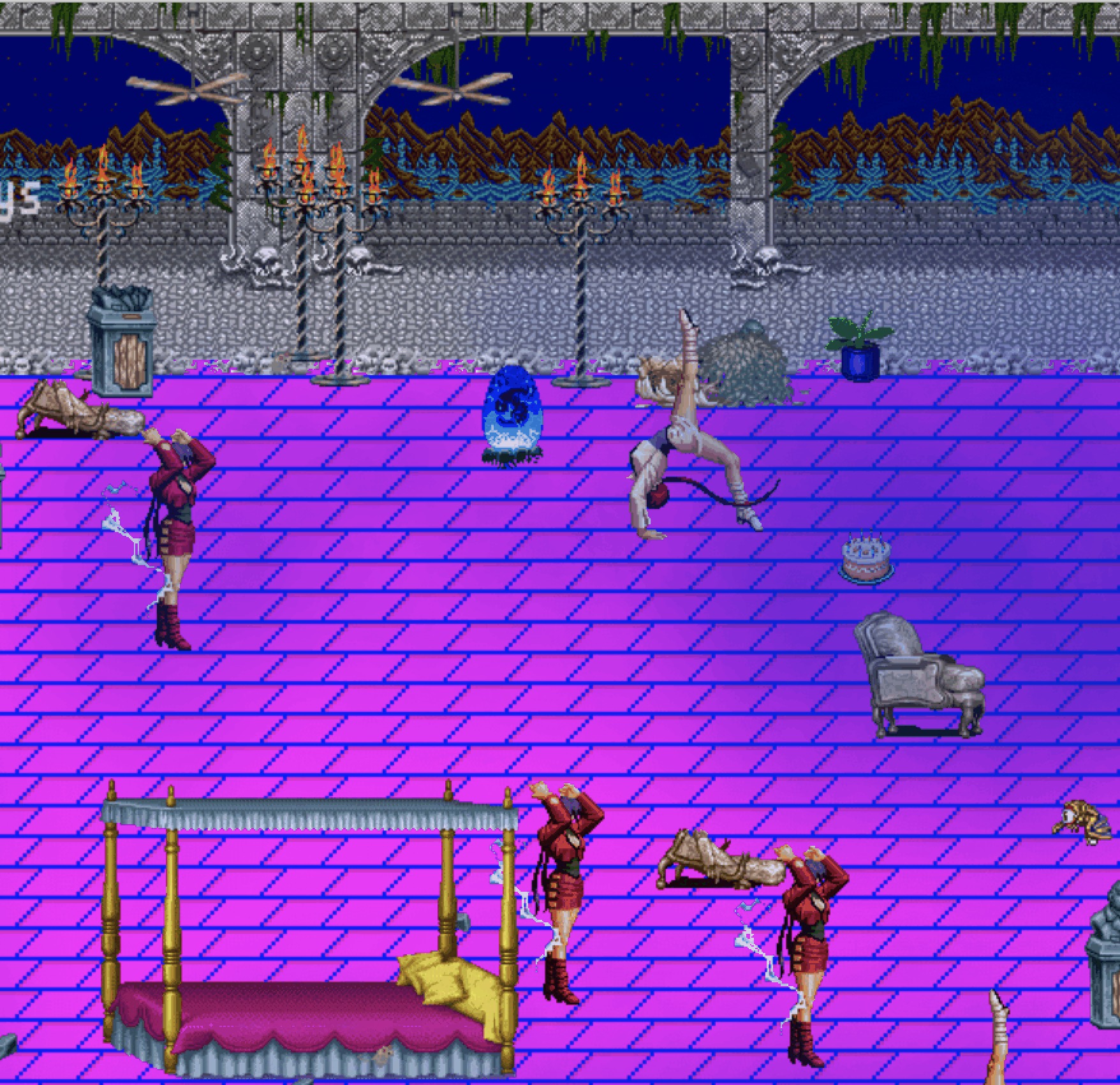

In Cassie McQuater’s work, pleasure and paradox mingle: virtual installations invite viewers to inhabit pixelated patio chairs unfolded among fjords; paintings pulsate with vintage animation loops, edging their way toward the filmic; iconic female video game characters get re-contextualized against ornate, hypnotic backgrounds; and insomnia gets to claim the title of muse.

We spoke with Cassie about Google Earth; her background in painting; and what it was like to create the browser-based video game, Black Room.

Tell me a little bit about your upbringing, like how you made your way into becoming an artist as a career.

I have a degree in painting, an undergrad degree, so that’s kind of where I started becoming professionally interested in being an artist. But then, other than that, I come to video games from an interesting story, which is that I wasn’t allowed to have a console as a kid but my grandma had one and she would stay up all night playing video games, as a way to help her deal with insomnia.

We would have sleepovers, as you do when you’re a kid with your grandma, and I would just sit there and stay up all night watching her play these games and they just became like my fairy tales. I loved talking to all of the different non-player characters (NPCs) in the world and I just fell in love with that type of intimate setting.

When you were playing games, were you always a spectator?

There were times where, if we had family parties, the console would be out and so my cousins would be there and we would play, but I really enjoyed watching. When I did get to play, I really just enjoyed talking to the NPC’s and wandering around these open worlds. I didn’t really care about fighting.

So you were interested in the spaces in which these games were created as opposed to whatever the explicit goals were for the games themselves?

Yeah, I would always get really annoyed at having to beat dungeons in order to go to the next town where I could talk to all of the NCP’s. To me, that was the game. The dungeons or whatever were just annoying parts I had to get through, or Grandma had to get through, to get to the fun stuff.

Got it. When did you first start creating stuff on your own, just for your own enjoyment?

That started in high school. I went to a Catholic school, so there wasn’t a lot of artistic freedom, so to speak. I would do teen things, like paint my uniform and try to get away with wearing a tie-dye shirt underneath because you couldn’t. If they saw any part of your undershirt and it was not white, you’d get detention.

I always kind of saw myself as an artist so even then I would paint, just nothing good obviously, like acrylic paintings of women in graveyards or something like typical-amazing-high-school style. And then, also, I didn’t have access to a computer. I grew up in the AOL Instant Messenger generation, so we had dial-up for the entirety of my high school and we only had one computer, family of five, and it was in the basement. I could only use the computer from 8:00 to 8:30 p.m. and only if I had my homework done. That type of thing.

I didn’t really have access to thinking about a computer as a place where art can happen until the end of college, in my early twenties.

Was there an artist that jumped out at you that maybe helped push that approach along? What was it about mixing media that was attractive to you as a creator?

Well, during college, I was a twenty-year-old woman and so I was interested in the work of mostly ’60s style painters, especially like Mark Rothko, Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg and all of the big names that you come to appreciate when you’re twenty or whatever.

Then, there’s something about collage, where you’re using materials that people are going to recognize and so it gives them a way into the work, but then they see these things they recognize and all of a sudden, they’re in this new context. That causes you to really think about the original intent of the collaged item.

But it’s basically been ever since falling in love with collage through painting. My entire work, even my digital work now, is all kind of based on the idea of collage.

Yeah, it’s interesting. You get to draft off of people’s associations with something specific and then get to play with it, subvert it, and comment on it in a new and creative way. How did you make decisions about what to re-appropriate for your work?

My work has always been really serialized in the sense that I will pick a topic and then dive deeply into that topic and emerge a year or two years later with whatever finished thing I’m making.

I usually have the idea; I go out and find the material; and then the idea might morph and change depending on the material I find.

Coming out of college, did you make a conscious transition into digital?

It all started with Google Earth. I would just be looking for these landscapes and it was just a thing I did for fun, to relax in the evening. Then I started getting really into the idea of draping my paintings because I was already making digital paintings at that point. So, I wanted to drape my paintings over mountains in Google Earth, just for kicks.

To do that, I had to learn how to write KML and XML which were the languages, Keyhole Markup Language, that Google Earth was kind of running on at the time.

I really liked the idea of an interactive world because in this old Google Earth app, you could run tours through different parts of the world where you’re walking, but it’s a first-person camera and you can say, “Go from point A to point B.” So, I would do these tours with all of these psychedelic landscapes with my paintings mushed into them. Just the idea of moving through a world of my work really hit me.

So then, I was talking to a friend of mine in 2013 about this experience and he was like, “You should try Unity. It’s this new videogame software thing.” It was free at the time. I think it’s still mostly free. So, I was like, “Okay.” So I just downloaded Unity and started putting random models in there and just making walk-throughs.

It was really immediate for me to be like, “Oh, I can do a lot with this. I can fuck around with this. I can break this. I can play with this.” So, from that point on, I was like, “I’m going to make a video game.” Then I made my first video game and after that, I was just completely hooked.

Being able to go inside of your work or somebody else’s work and just live in this alternate world, that really hit me.

I really liked doing stuff at very recognizable places like the Hoover Dam. I think that actually ties in with collage as well because you have all of these associations with these famous landmarks, so when you see something not right or added to these landmarks, even if you’ve never been there, basically, you notice that something’s wrong. I remember liking working with that tension. To me, it wasn’t really about the place at the time, it was more about the textures that I was making.

You mentioned earlier that you like to go really deep into your research. Can you tell me a little bit about your research process heading into Black Room.

It’s a game about an insomniac trying to fall asleep online. Actually, I suffer from insomnia and anxiety and the game did actually begin one night when I couldn’t sleep and woke up, went downstairs and started just like fucking around on the computer.

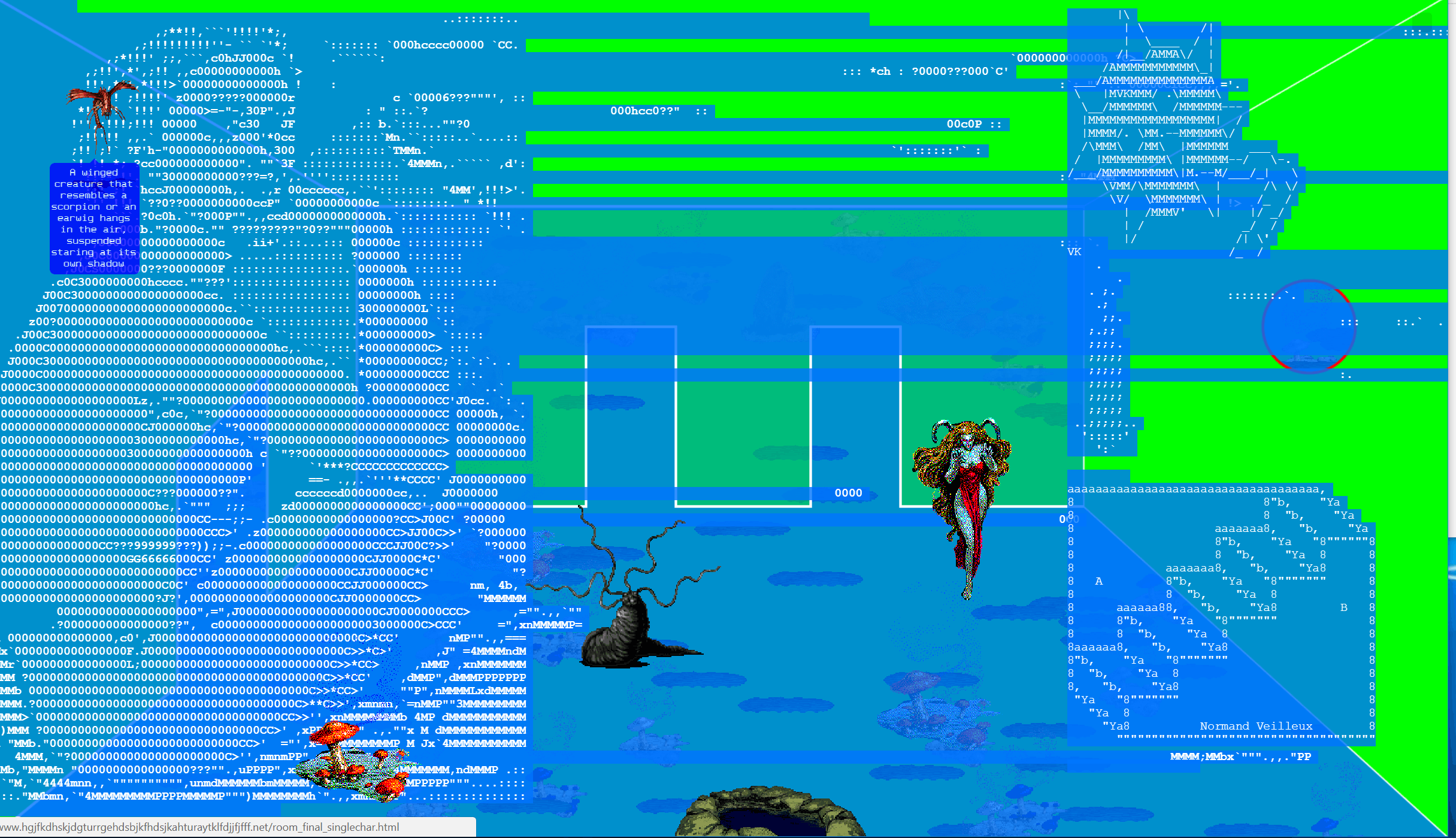

The original intent of the game was actually going to be a story told in the source code. It was always going to be an HTML-size game, but then you view source on the page and everything underneath the page is the game, so it’s kind of like a text-based game inside of the source code that you’re viewing. So, I called it View Source and I worked on that for a while.

I found this website of hobbyists who ripped all of these sprites. Sprites is just the graphical name for the data inside of a cartridge. So, this group of hobbyists rip all of these sprites from different games, like the backgrounds, the foregrounds, everything. They post them online as sprite sheets. They love doing this. It’s like, they see it as a kind of preservation, but also they have their own community around this. They have an extensive forum. They have extensive posts, weekly posts.

I was like, “These are so beautiful and they really bring back a lot of memories and associations,” and then I had this realization and I was like, “You know, my grandma was an insomniac and she used to stay up late playing videogames and now I’m making a game based on my insomnia.” It just kind of connected.

Video games, I mean, they help you fill time and space, as I said, turn yourself over to another experience that can be very restful in a way when you can’t get rest on your own.

The game is available on itch.io and that platform is typically used for game creators looking to sell their work and obviously you’re trying to kind of establish what you’re doing in a different way. How you think about that distinction between making games for commercial use versus making games or interactive work in an artistic context?

Yeah, well, I think I’ll start by just describing a little what the gallery setup looks like and that will lead into more of that feeling. So, in the gallery right now, we have an interactive station with podiums set up. The game itself, which you can actually play, is projected big on the wall, maybe 15, 20 feet. Then we also have two large TVs set up back to back and on those TVs we have five different levels, five in the front, five in the back of the game. The levels, when I say levels, I refer to the parts of the game that are the eyeball tableaus, I call them “strange visions.” So those are the parts of the game with the very visible, understandable women characters dancing around in different environments.

What that kind of dynamic offers is something for somebody who might be more of a passive viewer, somebody who comes into a gallery, an art gallery, doesn’t know anything about games, is used to just going into the gallery and looking at stuff, so the TVs kind of offer that vantage point.

And then it also offers the interactive experience for people who come in and are interested in games, but not necessarily interested in the “art gallery” situation. They’ll approach the game and play that and then maybe become more interested in the videos.

I wanted it to be an experience that could be open to both of those mindsets and maybe help each of those mindsets meet more in the middle, cross over and be interested in each other’s things.

And as far as selling the work, too, it’s really important for me to have the entire game online free for anybody to play at any time.

Could you tell me a little bit about the approach of viewers, for people who experience those things? Expectations they might have versus downloading it on the website versus going to see it in a gallery context versus having it in private collection?

I think they’re all very different and I think that’s good. I don’t see the point. I mean, why not be numerous with your experiences or your work? There doesn’t need to be one way to consume a particular work of art, especially with a digital work.

There’re so many different ways we consume media, so the work that you play alone on your computer at night is never going to be the same as a work that you go out of your house to experience publicly. That’s going to be a different experience no matter what.

I think that’s one of the beautiful things about new media, especially, or games even. Where you are when you play these things or look at these things automatically affects how you feel about them.

What do you feel your relationship is to the video game community, both video game players and also creators, because you seem sort of in between those two worlds.

Yes, I feel like I’m very much in between those two worlds and I see myself first, I think, as a net artist, as somebody who’s interested in examining and making work about the Internet.

But when I make that work, I primarily express myself through interactivity, through games or other types of interactivity. I feel like I’m very firmly in the middle and I like both. I like being in this nebulous area where I can’t say I’m a video game artist, period. I can’t say I’m a new media artist, period.