Thanks to their secret, shared obsession with video games in the Kuala Lumpur creative scene, artist Mun Kao and writer Zedeck Siew now run the creative collective Centaur Games. Based between Malaysia’s capital and the seaside town of Port Dickson, the two work on projects that enhance the tabletop role-playing game experience.

Their ongoing project, A Thousand Thousand Islands, is a collection of illustrated zines rooted in Southeast Asian folklore that can be incorporated into such strategy games. Fusing archive with imagination, the duo call their research practice a ‘mythic history’—the aim, they tell us, is to decenter Anglo-European settings as the center of fantasy.

Mun Kao and Zedeck sat down with us to speak about their anticolonial research methods, their collaborative working process between art and writing (‘it’s like growing a tree,’ Zedeck says), and how games, at their core, are a conversation.

When did you first know that you wanted to do something creative with your life?

Mun Kao: I grew up in Singapore with very few friends, so I was bored all the time. I drew to fill the time.

Zedeck: When I was in my twenties, we moved to Kuala Lumpur, the big city. There is an aspiration to make an important work—’the great Malaysian something.’ So, the creative journey for me is makin a return. I moved back to the home home I grew up in, in Port Dickson. It mirrors a relative return to what I grew up loving: this landscape, these trees, these animals.

Port Dickson is the juxtaposition of a petroleum and beach town. The petroleum companies used to be owned by Dutch and US companies, Dutch Shell and Exxon-Mobil, and now they’ve been bought over by Chinese and Southeast Asian companies. There’s shift in where colonial power is located. I’m living in a space and trying to figure out what that space means.

How did you meet and begin to collaborate?

Zedeck: Instead of going to college, I started working. My first job was writing for, and then eventually editing, a local arts journal. Being in that scene was how I met Mun Kao. He was emerging as a visual artist in that scene… and he’s obviously very good.

Mun Kao: I met Zedeck during a period when I was new to the Kuala Lumpur creative scene. The scene is small. What is even smaller is people who play games within that scene.

Zedeck: It was a dirty secret that you carry within yourself as you’re amongst these champagne-sipping gallery-goers.

Mun Kao: Gaming was this super smelly, nerdy, cyber café thing. It’s very different now. When we talked about games, we were so excited—the “smell” of playing games never really worn off. Because of genuine interest, but also because of guilt, we turned the games into work.

Zedeck: We started making analog tabletop stuff, because neither of us had a digital coding background. We also loved grand strategy games.

How did A Thousand Thousand Islands come to be? What were the interventions you hoped to make in the way tabletop experiences are played?

Zedeck: We started meeting other people who were into playing games in the Kuala Lumpur scene. One of our friends said, “Hey, why don’t we play Dungeons & Dragons?”

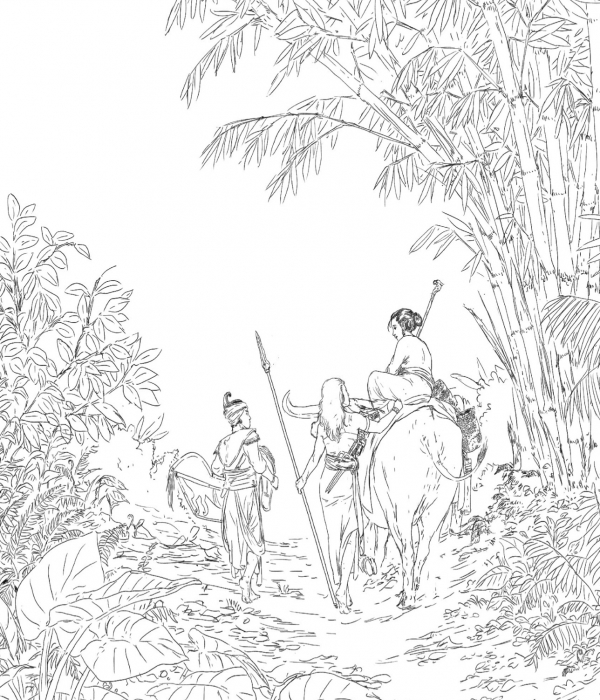

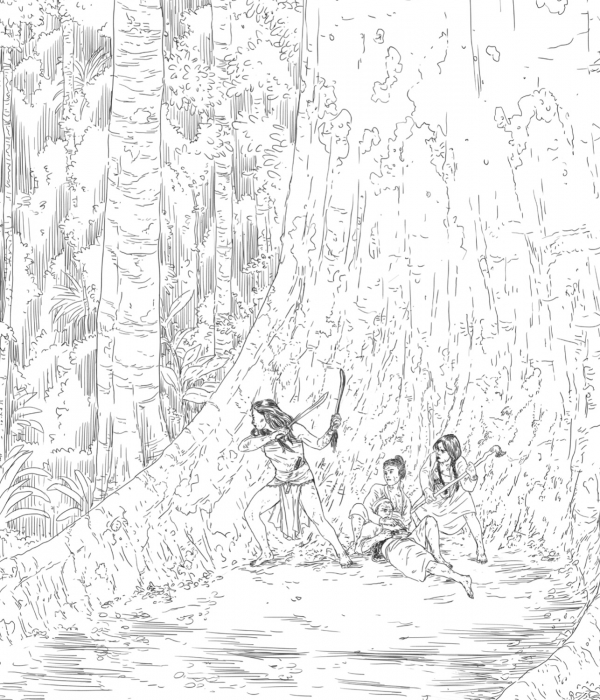

Mun Kao: We played a lot of board games. I stopped drawing for a while. What D&D reignited was a love for fantasy—it got me back into visualizing and drawing. I was exploring moving the center of fantasy to Southeast Asia—away from Anglo-European setting. That took two years of drawing, exploring, researching, reading.

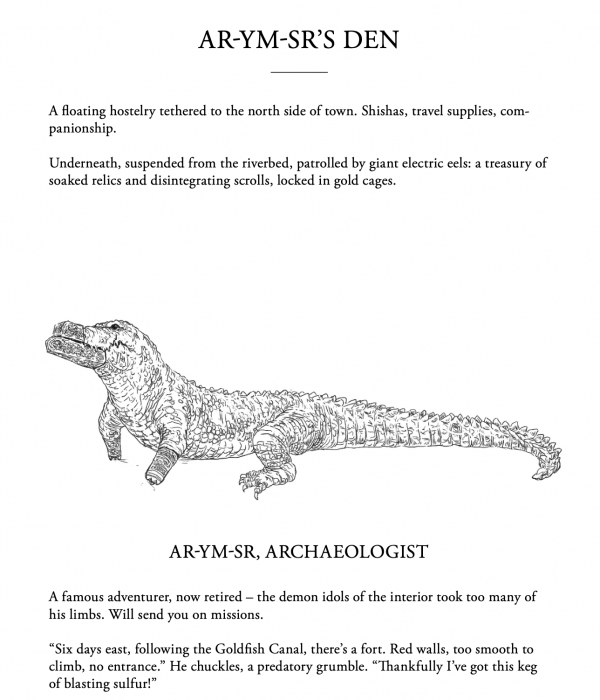

I’d made a lot of zines before. I wanted to create a fictional world where the drawings that make sense to each other. I was thinking about a river port ruled by crocodiles. What’s also interesting is that Zedeck also was working independently on something similar. He was also exploring Southeast Asia fantasy, and he also had a crocodile adventure or setting.

Zedeck: It was a mirror of our dark secret of, “We play games as well.” As Mun Kao was making these drawings and doing this research, I had been playing a lot of roleplaying games online, and was part of a community of roleplay game designers on Google+. There was a community that grew up around that. I was writing an adventure inspired by a local Sarawakian story about a man-eating crocodile. I had a draft of that already when Mun Kao came and showed me his drawings. I had to suddenly further expand my imagination! While the initial adventure was subsequently published separate from ATTI, I pushed further with Mun Kao, imagining a kingdom ruled by crocodiles. That became our first zine.

What drew you to the zine as a medium for game design?

Zedeck: Writing and art is game design. The illustration of a particular character influences the imagination of a roleplaying game as much as the rules you write for it.

The way the entries are written for encounters, for example: What does this single sentence make you imagine? How do I write this idea in a way that would get the hypothetical players imagining themselves in that situation? How do I write this sentence so that they would want to interact with this thing that’s going on? How do you make images that draw in the players to what you describe?

Tabletop roleplaying games are a conversation; how you get people into the conversation is design. How you describe a particular place or how you’ve drawn a particular character, are equally important as the mechanical rules.

How are your respective research processes? How are you thinking about colonial histories, and rewriting colonial history when you’re imagining this world?

Zedeck: On a conceptional level, Mun Kao was pretty clear about how the whole project would be very self-consciously set in the pre-colonial era. The way we addressed Mun Kao’s initial thing about shifting and reframing the center of fantasy, was “Let’s just exclude the conquistadors altogether.” We also excluded the nation-state that came after the conquistadors. The reason we started exploring these images was because imaginings, fantasy, and mythic history in Malaysia are all predicated on a very particular look.

Mun Kao: They’re all centered along ethno-nationalist lines.

Zedeck: Malaysia was colonized most heavily by the British. Whiteness, Christianity and all these kinds of assimilation behaviors, the nation-state of Malaysia started imagining these things as stuff we did ourselves, in our past — our previous polities as being these vast Malay, Islamic empires. Even the post-colonial nation-state was a strong reaction to and mirror of colonial power. Both of those things were things that we were trying to avoid. It was just is boring. We had to look for alternative, mythic imaginings.

Mun Kao: It really doesn’t do justice to the history of this region. If you look at the history, race and nationality is definitely not how people interact with each other. In A Thousand Thousand Islands, we very consciously and actively tried to work against the lens of ethno-nationalism. Just to do, create, images that celebrate that fluidity of identity. The porousness. Make fantasy out of it; make it fun. Just try to capture that non-ethno-nationalist view of things. That’s the biggest thing I contend with, with regards to colonialism.

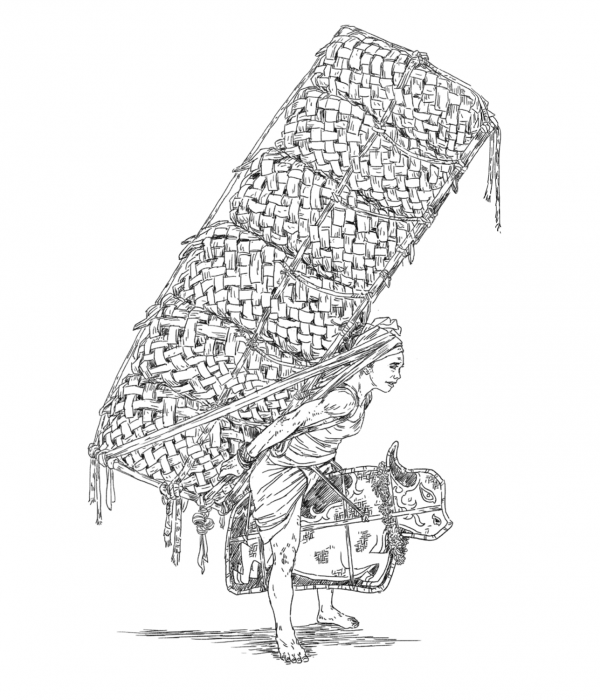

I try and read and collect as much imagery as I can. Most of this imagery is all taken by Europeans. So you have to be careful with how you engage with it. This type of thing can be self-fulfilling—the colonialists show this, and then you believe it, and you perpetuate it, and then it becomes real. With A Thousand Thousand Islands specifically, I know it’s a fictional world, but also we really do not want to perpetuate anything of that sort.

Zedeck: We’ve ding-donged about this a lot: How do you portray a mythic history when your only sources are “objective” facts—colonial-era records or epigraphies? We read and consumed as much as we could, but also read with suspicion and with a sense of slyness. The other alternative is that you become a post-colonial historian—that fetishization is also a trap.

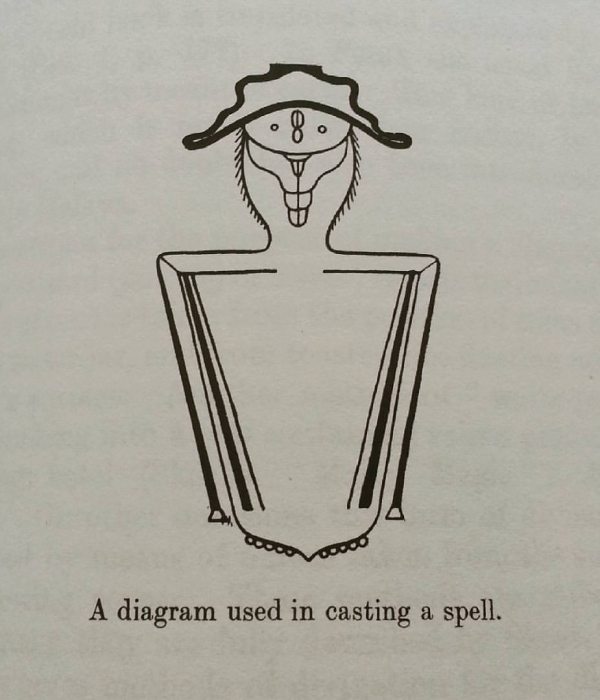

The conception of objective history is a modern notion. Epic poems in Sanskrit are not actually historical texts; not in the sense of the Western “What happened?”. That’s why the use of the word “myth-history” is very useful to us. It does give us a kind of leeway to imagine. A very big reference for me when I write stories about the past in this region, is a very, very, very colonial text called Malay Magic, an ethnographic work by Walter William Skeat. It’s the least woke colonial source. So it’s a collection of stories about magic, or magical practices and magical folkloric practices, in the Malay Peninsula. Then he’s a colonial administrator, so he rubs shoulders with the local princes of the various states, and the Malay gentry,. He says, “Oh, so-and-so says that such-and-such person said that this was the story.” You get the sense that he’s looking at it all like, “What are all these strange and weird things that these savages believe?”

I like to believe that the people who told Skeat these stories know who their audience is. It’s a credulous white colonialist who wants to share stories of insane magic practices. So there is a sense of the puckish, “We’re going to feed you some bullshit story. Because it makes us look cool, and also it gets the interest. Because I know an uncle who is a real tiger…” I wanted to bring that playfulness to the project.

That’s relatively easier for me, because I’m working in text, and there’s the shape of narrative. Whereas Mun Kao’s issues are more concrete. “How would this particular costume look?” Or, “How do I imagine the fantastical cape on this particular kind of costume?”

What did your collaboration look like on a day-to-day level?

Mun Kao: We have different modes of working. The most common one is I draw a bunch of images, write some notes to Zedeck, and he goes wild with it. Sometimes changing the style, sometimes not changing so much. That’s the general way we work. It’s a mix of stuff that you get from reading books, seeing images, and personal experience.

Zedeck: There’s a process of composting. Mun Kao reads, hears, and experiences all these things. Out of that compost comes a batch of 20 to 30 images, which he then emails to me with his notes Then I bring my compost to it, what I’ve read, heard, experienced. So it’s very much like growing a tree.

Mun Kao: Lately we’ve tried swapping the order around, too.

Can you walk through the ideal way for users or players to work with the zines that you’ve created, and use that in their roleplay experience?

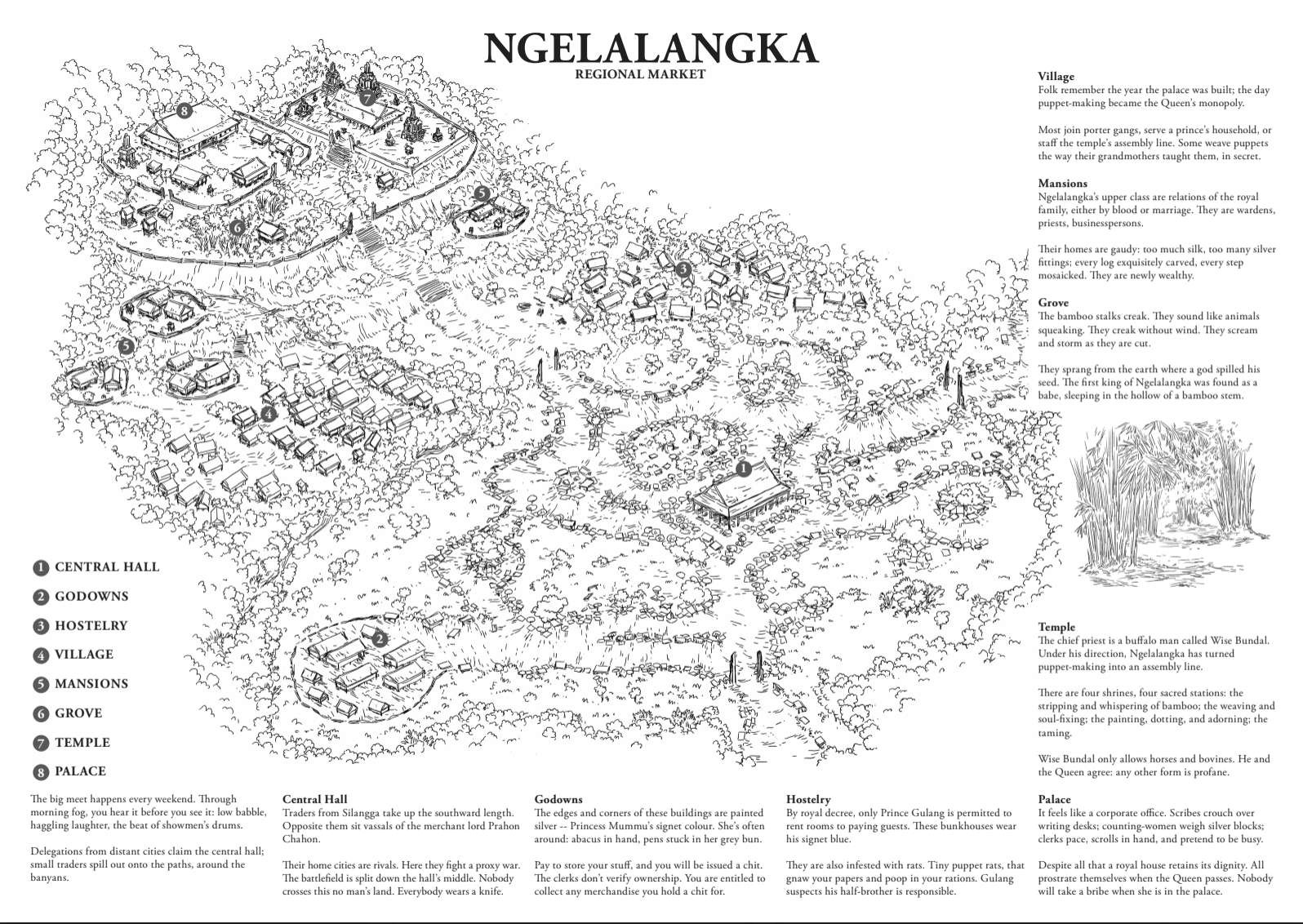

Mun Kao: The zines are quite text-light. The imagery is half of the work, really. The text is system-neutral, in the sense that there are no mechanics in it. Each zine is a description or an exploration of a particular geography or community. Sometimes they are literally islands, or just one village, or a forest. The frame of the project was “What is Southeast Asia like?”

Zedeck: The region that we are working in has no center.

Mun Kao: It’s a bunch of polities or communities trading. So what does this island have to have? What is it known for?

Maybe it’s known for this particular kind of sea cucumber that, when you eat it, gives you a particular kind of magical power. That’s how we keep it really short, but really expansive. These books are mainly aimed at people who want to run games, and are looking for an interesting locale or scenario or place to put their players in.

How does that compare to how people have actually implemented A Thousand Thousand Islands into their gameplay?

Zedeck: I’ve seen play reports of people using the zines—they make me happy, because it’s a vindication that the zines have been used. I know people who have used them in traditional Dungeons & Dragons games where there’s lots of combat. There’s also people who have run it in storygames, which are games that are more about players coming together and workshopping a narrative. Imagine a bunch of screenwriters sitting down and talking about where the characters are going—that’s the game.

Two of the zines that we published so far have just been purely images—collections of drawings that Mun Kao has made of people and places and things. There was someone who said that the Southeast Asian setting is sometimes difficult for people to grok. If this was a group playing in the West, for example, they say, “Oh, I don’t feel comfortable imagining that space.” But, so, this person said, “I just gave my players this zine of drawings, and that was the key that let them play.” You get a sense of the costuming or the ways the tools look. One of the drawing zines has a description of fire starting or paddy harvesting tools. Those concrete details about the world really help players into the imaginative space. It was a point of pride for me.

Mun Kao: It’s surprising and humbling to see people do the work to incorporate our zines into their game. It’s not like you can say, “Okay. I didn’t do any prep. I’m going to put this zine down at the table, open it up, and I can run a game for my players immediately.” It’s not that kind of thing. What we wanted to do was create an experience or a collection of imagination that is fuel. It’s gratifying to see that it’s working the way we wanted it to work. The reviews say that the zine is that kind of powder-keg fuel—where it is a key to you imagining a world that you didn’t imagine before.