Darlene Barahona is expanding the boundaries of what it means to be a narrative designer. Born and raised in the ‘desert heatscapes’ of Los Angeles, Darlene has a background in technical writing, cultural anthropology, and writing for the screen. She is an advocate of drawing from real life experiences, using the storytelling engine Twine, and a game’s replayability. We speak here about what game narrative can glean from film narrative, how archetypes and mythology can prompt developing characters, and how her time in the Pacific Northwest propelled her into the world of games.

What got you excited about narrative in the first place?

I grew up in LA, and the city is one of my first major influences in life. My dad was a paralegal—he did lots of driving all over the city. Little Darlene always went with him everywhere. I remember driving to all of these new places in this massive city and always being amazed at the number of places and the different people, neighborhoods.

That instilled in me this desire for exploration and travel that laid a basis for my love of storytelling. My favorite parts of narrative that I like to focus on are world-building, environmental storytelling, and character design. It goes back to the traveling I did in my city. I remember my dad would give me a paper map (this is back before GPS) and say, “You’re going to navigate.” Many of those things seeped into the way that about storytelling and the world and how I build out worlds now in a digital space.

I was obsessed with The Legend of Zelda series. I played the hell out of Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask. Those were the first games that I played where I wanted to explore the world. I want to be in this space and role-play going around—experiencing everything and then finding the little things, talking to the NPCs, seeing how villages were built out and feeling immersed.

I did not grow up thinking I was going to be in games. I thought I was going to be an author. It took me a long time to realize that I didn’t necessarily enjoy the passiveness of writing a novel. My favorite part was the interactivity. I enjoy interacting with a world and an environment and with characters and I wasn’t going to get that by becoming an author or a screenwriter, which is why I began to deviate towards games—a space in which I can create spaces for people to explore and to feel immersed in.

You studied anthropology with a screenwriting minor. How did these two educational tracks shape your process?

I essentially dabbled in film when I was in college. I entered as a film major thinking I wanted to be a screenwriter. At that point, I was still trying to figure out my creative and storytelling heartbeat. What I learned in film, I still use today. But it still wasn’t really what I was looking for in terms of writing for games. If there’s anything that I learned from screenwriting that helped in narrative design, it’s probably pacing. In screenwriting, there is a strong need to keep the momentum going, to keep this pace, especially in the specific scene. Film gave me an eye for, “Has this scene in this game gone long enough?” It taught me how to be shorter and almost punchier with my writing so that I am getting in and out fast as they say in screenwriting.

If there is anything that’s done more in terms of learning narrative design and writing for games and world-building, it’s anthropology—studying other subjects outside of straightforward narrative design. Anthropology has given me the framework through which to think about building believable worlds.

Anthropology is the study of people; culture. When I think about what world I want to create in a game, I think about the things that make it believable. You start to think about society, economics, religion—things that build out a world. I’ve been playing through Mass Effect for the first time, and it does one of the most amazing jobs of taking all of those things into perspective, because it creates a believable world.

If you look at a lot of franchises that feel very robust, it’s because they have taken all of these facets of culture and society in mind—especially if you’re thinking about sci-fi worlds and fantasy worlds. Anthropology gives me the most tools to do environmental storytelling and create believable characters.

I found my place in anthropology. I also think that things like psychology, and even mythology and archetypes are important to storytelling. What roles are the players going to inhabit? Perhaps what other roles are NPCs going to inhabit? That’s a really good foundation for creating not just a digital game but also tabletop games.

That thinking about archetypes is a really interesting way of beginning to build out a tabletop role-playing game. When I talk about the archetypes, there are many ways to think about that. Essentially, you have Carl Jung’s archetypes, you have Myers-Briggs, even astrology can be considered its archetypes as well. All of those are really good tools for building out characters because they all inhabit a specific role. They give you a good starting point for thinking about characters and the roles within a party, or whatever you’re trying to build.

What was your first interactive world-building project like?

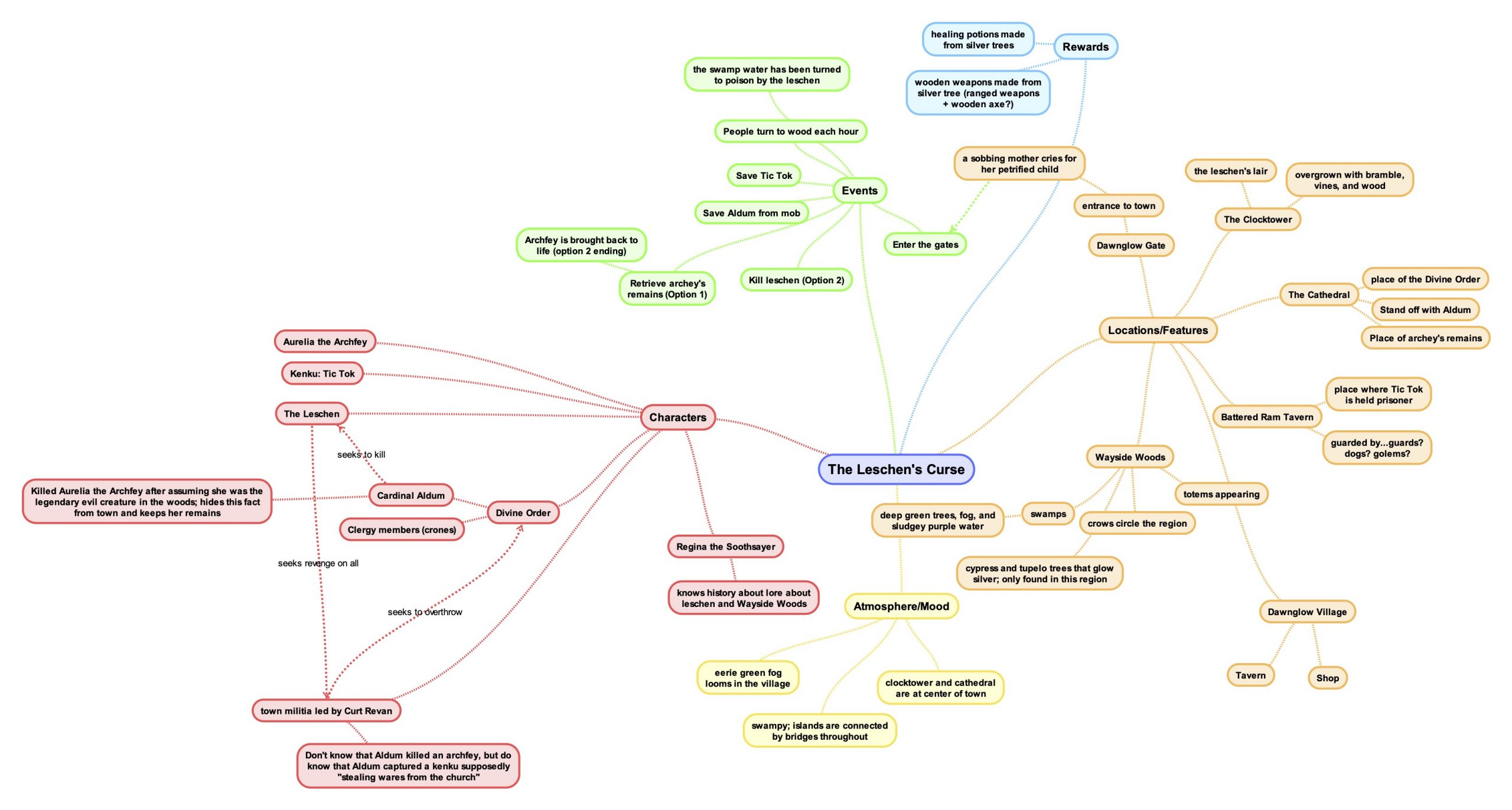

One of my first deliberate projects was Port Madrona, which was part of my curriculum at the University of Washington. I worked with a team—luckily, we were all very, very into narrative and storytelling. We decided to create an experience that is essentially a visual novel with game elements.

That was the first time that I got to think about and implement my love of world-building and character design. I had to figure out how to build texture into a universe—because, world-building, creating characters, creating the NPCs, making something that feels real is adding texture to a world; making it feel tangible. You can interact and make a difference.

To build a world, you have to think about so many different scales—there’s the levels, character design, and the meta texture of the world as a whole. How do you think about these levels and scales of the world?

The first thing is figuring out what the boundaries of your worlds are. With Port Madrona, we were under time constraints, so we knew that we didn’t want to create anything too massive, or an entire universe. We picked a location that we were all familiar with, which was a spooky little rural town in the Pacific Northwest. It made a lot of sense, and so we were able to find a lot of the inspiration in our backyards, on road trips that we’ve taken. So, first—what are the boundaries to the world?

Second, when I’m creating a world, I already have some experiences in the back of my mind. Maybe it’s something that stood out to me on a road trip. Maybe it was an exchange I had with a random person. Maybe it was a street sign that I thought was hilarious for some reason. World-building continues with the personal.

One of the most important things about narrative is to constantly be having very human experiences by traveling, experiencing, going out into the world and talking to people. That gives you an understanding of interacting with the real world? What are the things that stand out?

Third, nothing beats a vision board. I will stand by vision boards 100% because they give you the look and feel of what you want to create. You start with the fun stuff—weird little locations, things that you would be interested in interacting with. Personalities that you would perhaps be interested in interacting with, and then also, thinking about those socio-cultural aspects again. What is the culture like? What are people like? What are the reasons for this? Are there any events or rituals that define culture within the boundaries of the world you are creating? The answers to those questions will help build out a believable world; make it something that feels real and interesting to those who inhabit it.

Do you have a specific example of a moment in Port Madrona taken from a real experience that you had?

Even the name Port Madrona comes from experiences and things that we’ve seen. There’s a thing called a Madrona tree and it is a real tree that grows in the Pacific Northwest, and this game is supposed to have elements of horror. It’s a dark humor game. We wanted to add in those more spooky elements. This Madrona tree has a red bark and when it rains, which it often does in the Pacific Northwest, it looks like the tree is bleeding. It goes from a light red to a deep red and looks pretty cool and pretty creepy. We thought the name that should define this town—the Madrona tree encapsulates that strange, weird, unexpected feeling that we were hoping to capture with this small world.

What tools do you use for vision boards and narrative writing?

My biggest tool for vision boards is Pinterest. It gave us a visual language to understand what we were going for when we wanted to create this world. In terms of what other programs we use, we ended up creating the game in something called Ren’Py—it’s a visual novel game engine that lets you build them from the ground up. Normally, I use Twine to build out games. This is the first time I used it because we didn’t want to include visual elements.

I normally start with pen and paper, which many other narrative designers might deem crazy. I can’t handle the destruction of a computer and the internet. I normally start thinking about conversation flow and progression through pen and paper. I have a journal that is specific to conversations that I want to write and stories.

Once I have my basic structure and I’m not writing out full pieces of dialogue, I’m building out the structure and putting in very brief filler dialogue—at least it gives me something to work off of. Yarn Spinner is being another really good one that I’ve enjoyed using in the past. I will write directly into those tools and start creating those dialogues. The nice thing about writing directly into a tool is that I get to refine and test the flow as I go so that I’m getting a feeling for pacing.

In traditional screenwriting, people prize ‘show, don’t tell.’ In games, when is dialogue necessary?

In games you have to give players what’s called player agency. People do have to feel like it came from them. that show don’t tell in a game would be like when do you have a player act and do something? Make it part of gameplay rather than part of the story. Storytelling in a game should be pushed into the gameplay rather than, for example, cutscenes because then you create cutscene soup where it’s like, “I’d much rather be watching a movie at this point.”

As a game writer, I also need to know when the game mechanics and the gameplay should carry the story rather than some side conversation or a cutscene. It should always feel like the player is the one making a difference in the world and the player is the one who is pushing forward the story, not some passive listening to this person talk. That is not the thing that should be pushing forward to the story.

Your Port Madrona team mentioned how replayability is really important for the game and the players. You can reread or rewatch something, but you’ll have the same ‘experience,’ technically. What do you hope a replayable game can do for a player’s experience?

Replayability is a way to discover an experience like wider parts of a game or a world. For example, Mass Effect lets you experience different moral quandaries, which is very, very cool. In RPGs, you get to make different types of decisions, many of those being moral decisions and exploring the multiple ways in which things could have gone are fascinating.

Being a writer, it’s wild to think that someone who plays one playthrough is not experiencing the entirety of the content you have created. I want to experience all of that. I want to see what could have been different and what could I have done differently, how would that have changed, how would that have changed for the world, how would that have changed perhaps NPCs or companions or something like that.

Seeing those little changes in a game is very cool. That all lends to the replayability of a game. I don’t think that every game needs to be replayable. Realistically, many players don’t replay games, which is fine. It’s creating a game with multiple branches but assuming that somebody will only play that game once. It builds a very unique experience for a player. They get to build, they get to create the storyline as they see fit.

That goes back to player agency where the decisions made affect the world. Sometimes, it’s not necessarily about replayability, but it’s about the things that you chose not to do or the things that you did choose to do. Making a decision and there being consequences, makes decisions feel more impactful.

Sometimes, it is replayable because there are many paths that you can take but that’s not the exciting part. The exciting part is, “Oh, my God, I did this thing. Now, it cuts off this other option and now it’s going down this path instead. There are things that now I won’t be able to see because I’ve made a decision otherwise.” It makes decisions carry a lot more weight to know that you have affected the world in this way. Something will happen in this other thing won’t. That’s why a game is replayable—you can explore what you didn’t go through. At the same time, it’s cool to know even if you decide not to replay this, things happened and I don’t know what could have gone differently.