Julian Palacios, the Milan-based creator of Cartas, describes it as being “a short narrative game about the journey of a man adrift.” It is, in fact, more specific than that, it being bookended by letters written by immigrants who traveled to Argentina at the end of the 19th century. The game seems most concerned with depicting the dysphoria and disappointment of immigration, particularly as it’s described in the letter that is read aloud at its beginning—that of open hostility, constant alienation, racial abuse, feeling alone in an unfamiliar land. It captures all this through abstract, dreamlike segments that see you passing through the geometry of the game’s virtual scenes, pushed into the black voidscape beyond, where you become utterly lost.

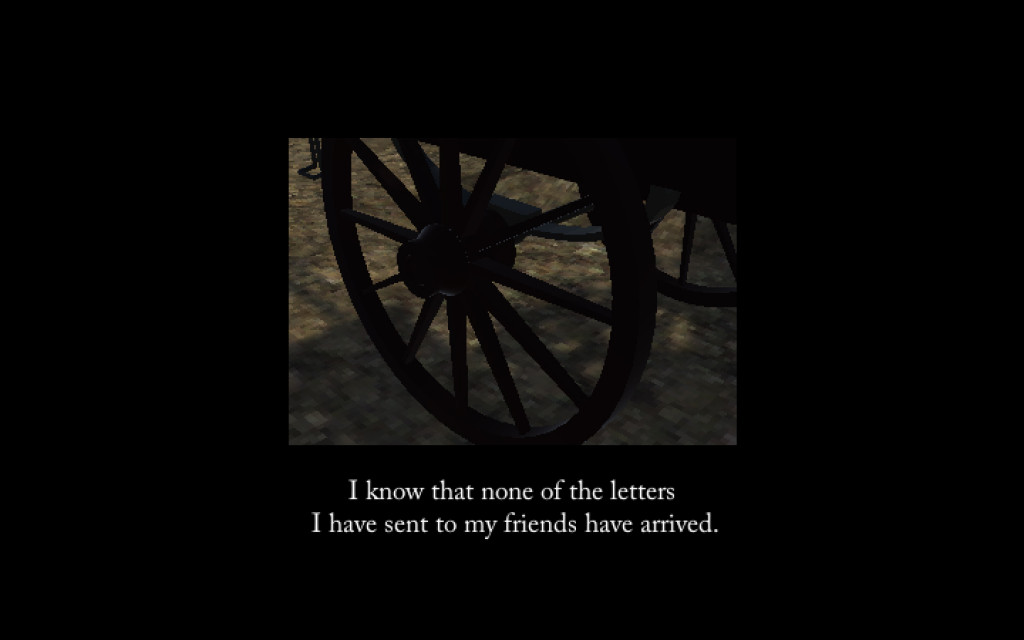

The presence of the void is dominant from the start. You see a square cut-out in front of you, surrounded by the total blackness, and inside this square is shown a cartwheel as it spins across gravelly terrain. You cannot move but you can look around during this scene. However, be that almost the only thing you can see is total blackness, your main informational stimulant is the sound of the horse-pulled cart coming from the cut-out. The set-up implies a bigger world than you are able to see, as if you have blinders on, but are still able to imagine the visuals you’re missing due to being fed sound cues. In total, it feels like the start of a hopeful journey, almost relaxed, like you were lazing atop the cart and riding toward a better future.

Then it all comes crashing down. For several minutes during this first scene, a voiceover reads the first immigrant’s letter to you over the sound of the cart and the clip-clop of the horse’s hooves. The letter is written by an Austrian called Jose Wanza, who sought a better life in Buenos Aires but ended up being treated like a slave—more on that here—and so any positive vibes the scene has are steadily dashed as you learn of his misery. When the voiceover finishes reading Wanza’s letter, the cut-out of the cartwheel suddenly expands to surround you with a full 3D world. It’s an astonishing transition. The cart you were looking at now appears empty and is without a horse. It loses momentum and rolls to a slow stop amid an empty natural expanse. There’s nothing here, nowhere to go, and you’re absolutely alone. It’s akin to waking up from a beautiful dream to find yourself in a grimmer reality.

This is only the start of the game’s brief journey. From this dull meadow that the cart sits within the void gradually absorbs you, expanding in presence with each new scene. The next one sees you stood on a dock at night, watching as a large ship comes in from the sea. It seems unsuspecting until the ship pulls in closer and you notice that it hasn’t slowed down at all, it heading right at you with a dangerous velocity. Unable to escape, the huge ship pushes you aside, and as its width swallows the dock it pushes you through the stone walls and into the voidscape behind them. This is where you fall eternally into the blackness.

But you don’t. A transition to another scene pulls you out of your indefinite descent, but the void is no less consuming. You find yourself in the middle of what could be a city. The only signs of this are the tall townhouses that sit separate from each other inside the voidscape. You travel to each of them, not knowing where to go, what to do, but discover that you can press ‘E’ when close enough to the jagged walls. Doing this causes them each building to vanish but adds the sound of a barking dog to the mix. The dog is unfriendly, aggressive, a signifier for the unwelcome gesture that immigrants like Wanza experienced. Eventually, you’re left with no structure, only the sounds of angry dogs and an all-consuming nothingness; lost and scared. Another scene after this one sees you in the crow’s nest of a large ship as it approaches a mountain from the sea and eventually moves through it. It reiterates the idea that the immigrant cannot truly dock on foreign land, that this land is a vacant construct for them where no home can be made.

The ending of Cartas seems to switch everything around, or at least aim to be more hopeful. A second letter is read aloud (it’s actually two letters jumbled into one) over the top of reversed footage of workers leaving the Lumière brothers’ factories. The writer of the letter is happy that they emigrated as they found work and are treated well, finding themselves in a more forward-thinking and polite society. It’s a note that’s at odds with the rest of Cartas but perhaps one that exists to better acknowledge the spectrum of the immigrant’s experience, and a reminder of why people thought it a good idea in the first place. But it leaves you wondering about the honesty of this letter given that it’s written from an immigrant back to their loved ones at home—they wouldn’t want to worry them. Or if the prosperity this particular immigrant is experiencing is true, whether or not it has a timer on it before they, too, feel alienated as the void creeps its way in.

You can download Cartas over on itch.io.